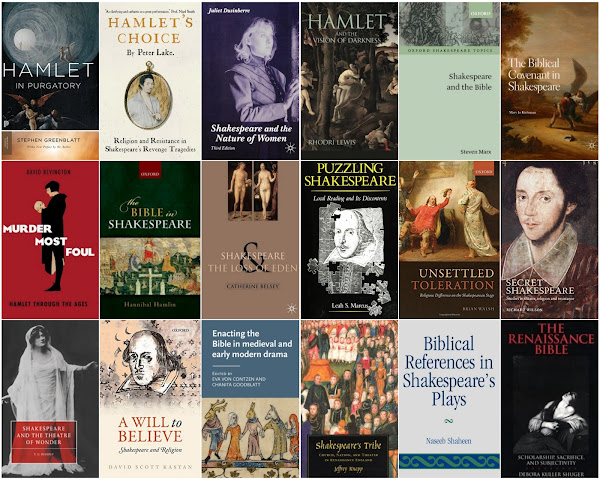

30+ Books for 30,000 views: A Celebration

This Monday I noticed: My blog has had more than 30k views from 83+ countries in 3.5 years! Thanks for reading! To celebrate, here are 30+ books related to Shakespeare/Hamlet/Bible/Religion, some of which I especially liked; others I wrestled with, tolerated, but found useful; plus a few I’ve recently acquired and am excited to read ( * ). By author: Shakespeare and the Grammar of Forgiveness Sarah Beckwith (2011) Shakespeare and the Loss of Eden Catherine Belsey (1999) Murder Most Foul: Hamlet through the Ages David Bevington (2011) Shakespeare and the Theatre of Wonder T.G. Bishop (1996) * Hamlet as Minister and Scourge Fredson Bowers (1989) The Bible in Shakespeare William Burgess (1903) Shakespeare and the Holy Scripture, Thomas Carter (1905) Enacting the Bible in medieval and early modern drama eds. Eva von Contzen, Chanita Goodblatt (2020) Shakespeare and the Nature of Women (3rd edition) Juliet Dusinberre (2003) The Biblical Presence in Shakespeare, Milton, and Blake Harold ...