Hamlet as Cassadra

Shakespeare’s Hamlet doesn’t merely have a number of allusions to prophets among its many biblical allusions; the play may serve as a reflection on what it means to be prophetic, and to strive to be more effectively and authentically prophetic, for both individuals and for art, and perhaps especially in politically dangerous contexts.

What does it help to oppose immoral and criminal behavior among the powerful, or in a corrupt system, if the result is that one’s life is snuffed out without reforming the corruption one spoke out against?

What does it help to claim one is a prophet, sent to correct injustices and corruption, if one is part of the corruption (prince Hamlet in a reckless moment kills Polonius), or if one drives people away (Hamlet bids Ophelia get to a nunnery, offends his mother and uncle) instead of winning them over to one’s view? (In this way, many prophets are dismissed because they are imperfect messengers. Instead of heeding or debating the message, the strategy is often to "shoot the messenger.")

What good would it be for a playwright like Shakespeare, or artists and filmmakers, to use their art to expose corruption, only to have plays and films censored and their means of livelihood closed down (as happens when “The Mousetrap,” the play in which Hamlet hopes to catch the conscience of the king, is halted when Claudius stands and calls for light)?

INCONVENIENT TRUTHS FROM THE SHADOWS

Many prophets speak inconvenient truths that speak to our “shadow,” addressing things that are true and important to hear, but that we may have blocked out habitually as individuals, or systematically as a culture or society, or within politics and media. For Hamlet, his truth is that Claudius murdered his father, and he spoke to a ghost to learn this, a quite inconvenient truth, especially for Claudius, but it sounds like madness.

Capitalism & Climate Change

Similar things occur in dynamics with stories in the media and our habitual ways of thinking. For example, capitalism says, “Buy! Consume!” - but climate scientists tell us, and activists remind us, that material habits and consumption, especially in more developed nations, may doom the planet unless we rethink our system and our habits.

US Military Spending

Or for another example: In the US, politicians warn against the dangers of reducing military spending, telling us to be afraid of what enemies and terrorists can do. So the US, by some counts, spends more than the next 7-8 biggest-spending countries (by other counts, more than all our allies and enemies, combined) on military. (These statistics vary according to what is included: What about secret spending on covert activities? What about veterans' benefits for past wars, and interest on the portion of the national debt related to past wars? As one Wikipedia entry on US military spending notes, "This calculation does not take into account some other military-related non-DOD spending, such as Veterans Affairs, Homeland Security, and interest paid on debt incurred in past wars, which has increased even as a percentage of the national GDP.")

This includes bioweapons research that is technically outlawed, but allowed if done for defensive purposes. Yet research supposedly for defense has often been described as “dual purpose”: The same research can inform how to *make* bioweapons rather than merely learn how to defend against them.

And so when a global pandemic takes place, it’s hard for the experts to tell whether it came from nature (and may have emerged regardless of human activity) as some (especially in the US) claim, or whether it came in part due to environmental destruction and deforestation, as others contend, or whether it may have come from a bioweapons lab in the US or China, either by accident, or on purpose.

So the prophetic Cassandra-voices tell us: Part of the tragedy and travesty is that when a pandemic unfolds, we simply do not know if it was from nature, or accidentally released from a lab, or released on purpose.

BIBLICAL PROPHET ALLUSIONS IN HAMLET

Shakespeare’s Hamlet includes allusions to many biblical prophets, including the prophet Jonah,

the prophet Jerimiah,

the prophet Nathan,

and the prophet John the Baptist.

The proliferation of prophet allusions is not accidental, I would claim.

And of these allusions are not in the narrow sense of a prophet as one that foretells the future, but rather, in the sense of a prophet as one sent by a transcendent and mysterious calling to speak harsh truths to sinners, frequently to their leaders as well, and usually at great personal risk, calling them to repent of injustice and sin.

CASSANDRA

When one is among those being asked to repent of some offensive but habitual and perhaps desired behavior, one often finds the voice of the prophet to be jarring or unpleasant (as in the Greek tale of the prophetess Cassandra, who has gifts of prophecy to speak the truth, but is cursed with an unpleasant voice).

The unpleasant prophetic voice is traditionally the “Cassandra” voice. And this seems to apply to Prince Hamlet as well, with Hamlet’s “madness” associated with that unpleasantness. This is also true of Shakespeare’s Cassandra in another of his plays, Troilus and Cressida, where a similar association is made between Cassandra’s prophetic gifts and a sense of madness, when Troilus uses an accusation of madness or brain-sickness to dismiss Cassandra's prophetic warnings:

Unfortunately, too often, what is other or unfamiliar, along with unpleasant truths, are sometimes associated with madness or incivility: What we’re used to is considered civilized, and what we’re not is considered uncivilized, barbaric, “beyond the pale,” or simply undesired as “too strange.”

GREGORY DORAN, CASSANDRA, & DEAF ACTORS

I got thinking about all of this regarding prophets and Cassandra's voice after reading a good piece written by Gregory Doran, Artistic Director of the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) in the UK. It was written in response to a critic who had misrepresented Doran’s view and complained about newfangled Shakespeare productions that experiment with gender and ethnicity of actors.

(For those who don't already know, I should note that another world-famous UK theater, Shakespeare' Globe, in London, has posted (for free on Youtube for two weeks) a 2018 production of Hamlet featuring a male actor in the rule of Ophelia and female actors in the roles of Hamlet, Horatio, Marcellus, and Laertes, as well as a deaf character interpreted through sign. Recall that in Shakespeare's time, all female roles were played by boys or men, and the scripts included playfulness about gender. This production does fresh things with such playfulness and more; I recommend viewing it for free if you can while it's available during the COVID-19 crisis while many stay at home. Other free videos of Shakespeare plays will follow in a series, each for two weeks.)

Gregory Doran of the RSC writes eloquently in defense of such creative casting, and in the process, notes a particular unusual casting decision. Doran writes,

I have had deaf or hearing-impaired students on a number of occasions in my years of teaching, and when I was a church music director, I worked with a number of people who interpreted the church services in sign language. But I still found Doran’s account of this anecdote very moving.

To some extent, it also describes Hamlet’s dilemma: He has spoken with what seems to have been the spirit of his dead father and learned inconvenient truths about his father’s death, but he fears that no one will believe him. It is somewhat unclear, whether his mother believes him after Hamlet kills Polonius and later seems to talk to the air, because she doesn’t see the ghost of his father that he claims to see (something I speculated about in the past).

Scripture speaks of those who have eyes but don’t see, ears but don’t hear. It criticizes ignorant and corrupt leaders, comparing them to “the blind leading the blind,” and yet in the Sophocles version of the Oedipus tale, the prophet/seer Tiresias is a “blind seer,” an irony. Yet perhaps as a blind person, he has developed insight or an inner vision of truth, not distracted by appearances, and therefore better able to grasp truth.

The same may be true of a deaf Cassandra, who pays attention and “hears” what is really going on in ways that others do not, distracted by too much background noise.

It also calls to mind a wonderful story by Raymond Carver called "Cathedral," in which a spiritually blind husband and host tries to describe to a blind man what a cathedral looks like. One can read the story as one about a literally blind man leading a spiritually blind man to transcend his own flawed assumptions and despair, or about a spiritually blind man leading a literally blind man, helping him to imagine what a cathedral is like, not only as a building, but as the product of ages of shared human labor and community.

"The blind leading the blind." But in a good way, adding a new layer of irony to the old saying.

DEAF VOICE AS GROTESQUE, & THE GOOD UNDER CONSTRUCTION IN ALL

Because the speech of a deaf person seems strange, some might think it lacking the polish or beauty of many of the best actors who can hear. Some might even describe the sound of their voice as grotesque, a word fiction writer Flannery O’Connor used in reflecting on fiction of the American South. O'Connor once wrote of a cancer home patient with a visible tumor as “grotesque” in a sense, but noted that the good is always under construction in us, and that this may at times leave us all appearing grotesque as we leave behind old ways and embrace the emerging good in us.

O’Connor wrote,

The good is under construction in Hamlet and other characters in Shakespeare’s play. But the prophetic “Cassandra” voice is often rejected precisely for that reason: The prophets who speak truths are always imperfect vessels, so they seem grotesque and are easily rejected.

Many of you may be familiar with a wonderful recitation by a deaf actress, recorded at the Globe Theater in London, taken from Shakespeare’s As You Like It, the speech of Jaques about how “all the world’s a stage,” which had the Globe Theater very much in mind:

https://youtu.be/NbIOZZy54EM

Among many wonderful aspects of the speech, it reminds us of our mortality. This is a prophetic reminder of the shadow, of a fact we would like to forget: We all die, eventually. Life is brief, so live it well, take care of it, and help others do the same.

But the speech reminds us of all this in a strange, but beautiful and perhaps unfamiliar voice, one that, hopefully, has the potential to jar us toward recognition.

What do you think?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Quotes from Hamlet are taken from InternetShakespeare, Modern, Editor's Version, edited by David Bevington, and courtesy of the University of Victoria in Canada.

Quotes from Troilus and Cressida are also from InternetShakespeare, in this case, the Modern Version.

Disclaimer: By noting bible passages in this blog, I am not intending to promote any religion over any other, nor am I attempting to promote religious belief in general. Only to point out how the Bible may have influenced Shakespeare, his plays, and his age.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading!

My current project is a book tentatively titled “Hamlet’s Bible,” about biblical allusions and plot echoes in Hamlet.

Below is a link to a list of some of my top posts (“greatest hits”), including a description of my book project (last item on the list):

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2019/12/top-20-hamlet-bible-posts.html

I post every week, so please visit as often as you like and consider subscribing.

What does it help to oppose immoral and criminal behavior among the powerful, or in a corrupt system, if the result is that one’s life is snuffed out without reforming the corruption one spoke out against?

What does it help to claim one is a prophet, sent to correct injustices and corruption, if one is part of the corruption (prince Hamlet in a reckless moment kills Polonius), or if one drives people away (Hamlet bids Ophelia get to a nunnery, offends his mother and uncle) instead of winning them over to one’s view? (In this way, many prophets are dismissed because they are imperfect messengers. Instead of heeding or debating the message, the strategy is often to "shoot the messenger.")

What good would it be for a playwright like Shakespeare, or artists and filmmakers, to use their art to expose corruption, only to have plays and films censored and their means of livelihood closed down (as happens when “The Mousetrap,” the play in which Hamlet hopes to catch the conscience of the king, is halted when Claudius stands and calls for light)?

INCONVENIENT TRUTHS FROM THE SHADOWS

Many prophets speak inconvenient truths that speak to our “shadow,” addressing things that are true and important to hear, but that we may have blocked out habitually as individuals, or systematically as a culture or society, or within politics and media. For Hamlet, his truth is that Claudius murdered his father, and he spoke to a ghost to learn this, a quite inconvenient truth, especially for Claudius, but it sounds like madness.

Capitalism & Climate Change

Similar things occur in dynamics with stories in the media and our habitual ways of thinking. For example, capitalism says, “Buy! Consume!” - but climate scientists tell us, and activists remind us, that material habits and consumption, especially in more developed nations, may doom the planet unless we rethink our system and our habits.

US Military Spending

Or for another example: In the US, politicians warn against the dangers of reducing military spending, telling us to be afraid of what enemies and terrorists can do. So the US, by some counts, spends more than the next 7-8 biggest-spending countries (by other counts, more than all our allies and enemies, combined) on military. (These statistics vary according to what is included: What about secret spending on covert activities? What about veterans' benefits for past wars, and interest on the portion of the national debt related to past wars? As one Wikipedia entry on US military spending notes, "This calculation does not take into account some other military-related non-DOD spending, such as Veterans Affairs, Homeland Security, and interest paid on debt incurred in past wars, which has increased even as a percentage of the national GDP.")

This includes bioweapons research that is technically outlawed, but allowed if done for defensive purposes. Yet research supposedly for defense has often been described as “dual purpose”: The same research can inform how to *make* bioweapons rather than merely learn how to defend against them.

And so when a global pandemic takes place, it’s hard for the experts to tell whether it came from nature (and may have emerged regardless of human activity) as some (especially in the US) claim, or whether it came in part due to environmental destruction and deforestation, as others contend, or whether it may have come from a bioweapons lab in the US or China, either by accident, or on purpose.

So the prophetic Cassandra-voices tell us: Part of the tragedy and travesty is that when a pandemic unfolds, we simply do not know if it was from nature, or accidentally released from a lab, or released on purpose.

BIBLICAL PROPHET ALLUSIONS IN HAMLET

Shakespeare’s Hamlet includes allusions to many biblical prophets, including the prophet Jonah,

the prophet Jerimiah,

the prophet Nathan,

and the prophet John the Baptist.

The proliferation of prophet allusions is not accidental, I would claim.

And of these allusions are not in the narrow sense of a prophet as one that foretells the future, but rather, in the sense of a prophet as one sent by a transcendent and mysterious calling to speak harsh truths to sinners, frequently to their leaders as well, and usually at great personal risk, calling them to repent of injustice and sin.

CASSANDRA

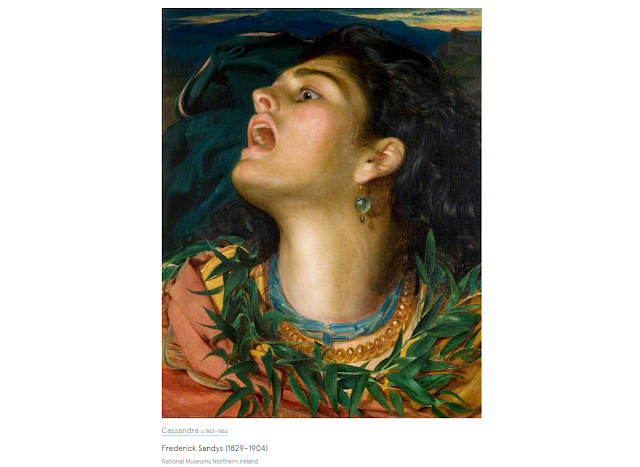

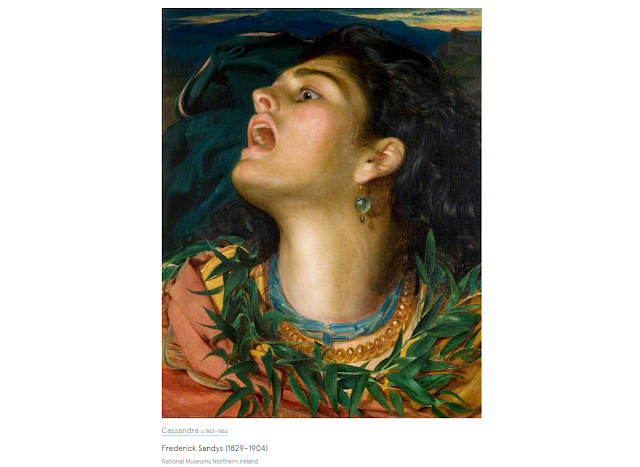

When one is among those being asked to repent of some offensive but habitual and perhaps desired behavior, one often finds the voice of the prophet to be jarring or unpleasant (as in the Greek tale of the prophetess Cassandra, who has gifts of prophecy to speak the truth, but is cursed with an unpleasant voice).

[Image from ArtUK.org]

The unpleasant prophetic voice is traditionally the “Cassandra” voice. And this seems to apply to Prince Hamlet as well, with Hamlet’s “madness” associated with that unpleasantness. This is also true of Shakespeare’s Cassandra in another of his plays, Troilus and Cressida, where a similar association is made between Cassandra’s prophetic gifts and a sense of madness, when Troilus uses an accusation of madness or brain-sickness to dismiss Cassandra's prophetic warnings:

TROILUS: Why, brother Hector,

We may not think the justness of each act

Such and no other than event doth form it,

Nor once deject the courage of our minds

Because Cassandra's mad. Her brainsick raptures

Cannot distaste the goodness of a quarrel

Which hath our several honors all engaged

To make it gracious. (2.2.1107-14)

Unfortunately, too often, what is other or unfamiliar, along with unpleasant truths, are sometimes associated with madness or incivility: What we’re used to is considered civilized, and what we’re not is considered uncivilized, barbaric, “beyond the pale,” or simply undesired as “too strange.”

GREGORY DORAN, CASSANDRA, & DEAF ACTORS

I got thinking about all of this regarding prophets and Cassandra's voice after reading a good piece written by Gregory Doran, Artistic Director of the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) in the UK. It was written in response to a critic who had misrepresented Doran’s view and complained about newfangled Shakespeare productions that experiment with gender and ethnicity of actors.

(For those who don't already know, I should note that another world-famous UK theater, Shakespeare' Globe, in London, has posted (for free on Youtube for two weeks) a 2018 production of Hamlet featuring a male actor in the rule of Ophelia and female actors in the roles of Hamlet, Horatio, Marcellus, and Laertes, as well as a deaf character interpreted through sign. Recall that in Shakespeare's time, all female roles were played by boys or men, and the scripts included playfulness about gender. This production does fresh things with such playfulness and more; I recommend viewing it for free if you can while it's available during the COVID-19 crisis while many stay at home. Other free videos of Shakespeare plays will follow in a series, each for two weeks.)

Gregory Doran of the RSC writes eloquently in defense of such creative casting, and in the process, notes a particular unusual casting decision. Doran writes,

I directed the RSC's first 50/50 gender balanced production in October 2018, Troilus and Cressida. But the revelation to me was not the power with which Adjoa Andoh played the Machiavellian Ulysses, or the wit Suzanne Bertish brought to the role of Agamemnon. The fact that the roles were played by women was the least interesting factor. Certainly the opportunity of having these strong experienced women together on the stage was refreshing.

The really unexpected impact was seeing the prophetess Cassandra played by a deaf actor, Charlotte Arrowsmith. Using her own first language, BSL (British Sign Language), Charlotte drew upon a lifetime of trying to be heard, to be understood, and the frustration of not being listened to, and she used that experience to create a devastating account of the prophetess blessed with the gift of knowing the future, but cursed that no one will believe her.

I have had deaf or hearing-impaired students on a number of occasions in my years of teaching, and when I was a church music director, I worked with a number of people who interpreted the church services in sign language. But I still found Doran’s account of this anecdote very moving.

To some extent, it also describes Hamlet’s dilemma: He has spoken with what seems to have been the spirit of his dead father and learned inconvenient truths about his father’s death, but he fears that no one will believe him. It is somewhat unclear, whether his mother believes him after Hamlet kills Polonius and later seems to talk to the air, because she doesn’t see the ghost of his father that he claims to see (something I speculated about in the past).

Scripture speaks of those who have eyes but don’t see, ears but don’t hear. It criticizes ignorant and corrupt leaders, comparing them to “the blind leading the blind,” and yet in the Sophocles version of the Oedipus tale, the prophet/seer Tiresias is a “blind seer,” an irony. Yet perhaps as a blind person, he has developed insight or an inner vision of truth, not distracted by appearances, and therefore better able to grasp truth.

The same may be true of a deaf Cassandra, who pays attention and “hears” what is really going on in ways that others do not, distracted by too much background noise.

It also calls to mind a wonderful story by Raymond Carver called "Cathedral," in which a spiritually blind husband and host tries to describe to a blind man what a cathedral looks like. One can read the story as one about a literally blind man leading a spiritually blind man to transcend his own flawed assumptions and despair, or about a spiritually blind man leading a literally blind man, helping him to imagine what a cathedral is like, not only as a building, but as the product of ages of shared human labor and community.

"The blind leading the blind." But in a good way, adding a new layer of irony to the old saying.

DEAF VOICE AS GROTESQUE, & THE GOOD UNDER CONSTRUCTION IN ALL

Because the speech of a deaf person seems strange, some might think it lacking the polish or beauty of many of the best actors who can hear. Some might even describe the sound of their voice as grotesque, a word fiction writer Flannery O’Connor used in reflecting on fiction of the American South. O'Connor once wrote of a cancer home patient with a visible tumor as “grotesque” in a sense, but noted that the good is always under construction in us, and that this may at times leave us all appearing grotesque as we leave behind old ways and embrace the emerging good in us.

O’Connor wrote,

Most of us have learned to be dispassionate about evil, to look it in the face and find, as often as not, our own grinning reflections with which we do not argue, but good is another matter. Few have stared at that long enough to accept that its face too is grotesque, that in us the good is something under construction. The modes of evil usually receive worthy expression. The modes of good have to be satisfied with a cliche or a smoothing down that will soften their real look.

The good is under construction in Hamlet and other characters in Shakespeare’s play. But the prophetic “Cassandra” voice is often rejected precisely for that reason: The prophets who speak truths are always imperfect vessels, so they seem grotesque and are easily rejected.

Many of you may be familiar with a wonderful recitation by a deaf actress, recorded at the Globe Theater in London, taken from Shakespeare’s As You Like It, the speech of Jaques about how “all the world’s a stage,” which had the Globe Theater very much in mind:

https://youtu.be/NbIOZZy54EM

Among many wonderful aspects of the speech, it reminds us of our mortality. This is a prophetic reminder of the shadow, of a fact we would like to forget: We all die, eventually. Life is brief, so live it well, take care of it, and help others do the same.

But the speech reminds us of all this in a strange, but beautiful and perhaps unfamiliar voice, one that, hopefully, has the potential to jar us toward recognition.

What do you think?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Quotes from Hamlet are taken from InternetShakespeare, Modern, Editor's Version, edited by David Bevington, and courtesy of the University of Victoria in Canada.

Quotes from Troilus and Cressida are also from InternetShakespeare, in this case, the Modern Version.

Disclaimer: By noting bible passages in this blog, I am not intending to promote any religion over any other, nor am I attempting to promote religious belief in general. Only to point out how the Bible may have influenced Shakespeare, his plays, and his age.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading!

My current project is a book tentatively titled “Hamlet’s Bible,” about biblical allusions and plot echoes in Hamlet.

Below is a link to a list of some of my top posts (“greatest hits”), including a description of my book project (last item on the list):

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2019/12/top-20-hamlet-bible-posts.html

I post every week, so please visit as often as you like and consider subscribing.

Great entry, Dr. Fried.

ReplyDeleteThank you, Michael. I hope you're doing well under the new state of things. Please keep in touch!

Delete