Honoring the (Sometimes Dishonorable) Dead in Hamlet, the Oedipus Cycle, & in a Time of Pandemic

Why do we honor the dead? How might we best honor them, if while living, some of them greatly dishonored themselves? What if their dishonorable actions are hidden behind a veil of family lies or state propaganda? In Hamlet as well as other famous works of literature, honoring the dead, usually the dead kings or princes, sometimes by avenging their deaths or bringing murderers to justice, is a recurring theme. I was reminded of this yet again over the past two weeks by watching the 2018 Shakespeare’s Globe production of The Two Noble Kinsmen by William Shakespeare and John Fletcher.

In The Two Noble Kinsmen, three queens complain that their husbands have been dishonored by being left unburied after battle, echoing a theme from Antigone in the Oedipus cycle. In Hamlet, the prince feels his mother and uncle have dishonored his dead father by not mourning long enough, and by what would have been considered a biblically incestuous marriage in Shakespeare’s England. Honoring the dead was a duty both plays assumed it would be wrong to neglect.

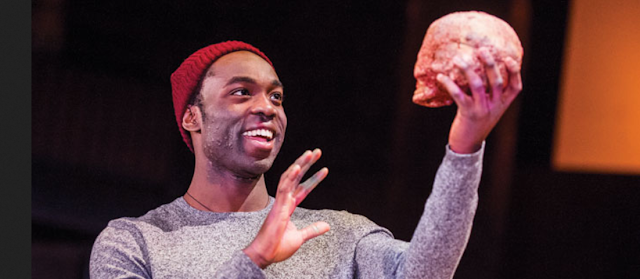

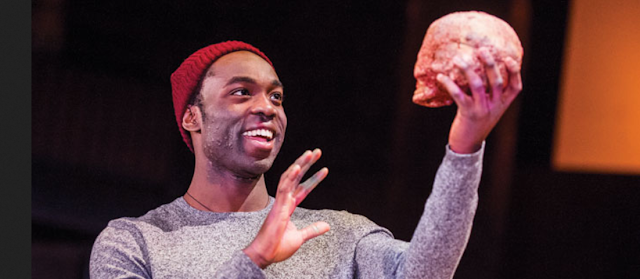

[Paapa Essiedu as Hamlet with the skull of Yorick in a 2016 RSC production. Photo via TheShakespeareBlog.com.]

OLD SCHOOL

Yet it’s strange to note how, in Hamlet criticism and in commentary on the Oedipus cycle, the predominantly male scholars and critics before 1960 tended to focus relatively little upon the sins of King Hamlet that landed him in purgatory; many assumed he was mostly a great and honorable king who had been dishonored in death by his brother and wife.

- Critics usually took Hamlet at his word, that his father was a goodly king.

- They often took Old Norway at his word, that Young Fortinbras had been scolded and his aggression successfully redirected toward Poland.

- One would think that, in Protestant England, more commentary would have assumed the ghost was from hell, a demon disguised as the dead king, sent to damn the prince; yet a surprising majority seem to have taken the ghost at his word, that he was only temporarily suffering while his sins were purged away.

G.R. Elliott’s 1951 book, Scourge and Minister (Duke University Press) is representative of this kind of approach, tending to place great trust in patriarchal authorities even when the evidence of the texts suggests flaws that may render kings untrustworthy.

Even Freudian criticism, from the start, has tended to focus more on the assumed dysfunction in the son (an “Oedipal complex”) than on the failings and dysfunctions of a distant, neglectful, and violent father.

The religious commentary of Roy Battenhouse went so far as to suggest that Claudius was not so bad a king, thinking him an able administrator (?!) and perhaps the best and most Christian thing for Prince Hamlet to have done for his own sake and that of Denmark would have been to forgive him, bide his time, and eventually assume the throne upon Claudius’ death. It would seem that, in the view of Battenhouse, personal piety as a cover for ambition and a path to salvation was more important than for princes to be champions of justice, if that meant opposing patriarchal authorities, which Battenhouse seemed disinclined to support (a traditional Christian argument based on passages from the letters of St. Paul regarding obedience to earthly authorities).

When Sophocles’ Oedipus cycle was taught in previous generations, students were often told that the visitation of the Sphinx and plague had been caused not by the injustices or bad karma of Laius, but by blind action of Oedipus, who unknowingly killed his father. The point seemed to be only that the murderer of the father had to be brought to justice, to the great shame of the son, rather than that a destructive and abusive man, father, and king, Laius, had himself been a plague, and the dysfunctional family needed to be confronted and stopped.

When Antigone was taught, the focus was often upon the stubbornness and pride of Antigone instead of upon the poor decisions of Creon or Antigone’s brothers. Instructors often claimed that the outlook of the Oedipus cycle’s original audiences was focused upon how all lives are ruled by fate. So in spite of a great deal of evidence of the flaws of men, perhaps the play was taught by men in such a way as to keep women in their place: Antigone, for all her good intentions, should not have disobeyed Creon’s decree. To paraphrase a contemporary meme, “This is why we can’t have good things: Women are unwilling to respect the authority of men.”

WHAT CHANGED?

So what changed, to make scholars have a greater tendency to consider the flaws or sins of men and kings, and to let the texts inspire more questions than easy answers? Was it the hiring of more women and people of color in English departments and the humanities? Or did the same social forces that led to these changes in hiring practices also encourage even white men to ask better questions about the texts? Perhaps both.

But now it is quite alright to ask at length about those sins that brought King Hamlet to purgatory in the first place, his violence toward Old Fortinbras that left Young Fortinbras without a father, his neglect of his son, the prince, and perhaps his neglect of his wife while he was off proving himself through violence. It is OK to ask if perhaps Old Norway was dissembling about his harsh words with his nephew, the financing of an army to go against Poland, and the humble plea for permission to march across Denmark on the way to Poland; perhaps all of that was to hide an attack that had been intended for Denmark all along.

HONORING THE DEAD IN A TIME OF PANDEMIC

On the topic of honoring the dead properly: During the current pandemic, there have been many stories about families unable to observe traditional burial rites, often unable to claim the bodies of dead family members, stories from China, Italy, Spain, New York, Ecuador, Iran, India, and many other places.

A pandemic doesn’t care about the innocent or guilty, the wicked or the just. Sometimes it spares the proud and selfishly negligent, but claims the selfless and heroic. In recent months, many people all over the world have known of family, friends and neighbors who were unable to honor their dead with anything that resembled traditional mourning rituals. For some of the more privileged, this might mean having to watch funeral services remotely on video provided by a funeral home while observing stay-home requirements and social distancing. For others, it may mean that the stench of the dead hangs over their city while the dead go unclaimed.

Certainly the COVID-19 pandemic has traumatized populations, and perhaps it is moving, and will continue to move, scholars to ask new questions about literature like Hamlet and the Oedipus cycle, as we ponder what it means to honor the dead.

More than that, a pandemic has forced many to reimagine what it means to honor their beloved dead, often not only at a great distance from the body of the deceased, but also from other mourners. While this may be good for some, and a positive and creative endeavor, it undoubtedly is also a challenge that has left many others feeling empty and robbed of the sort of parting rituals they would have preferred. We often feel great personal need for mourning, but also a duty toward the dead, their legacy, and the world.

If you were to die during this pandemic, how would you want people to honor your life and death? By risking infection in a community funeral service, and perhaps causing more deaths? Or would you prefer for the living to find other ways to honor your legacy? (I would prefer the later.)

HONORING THE DEAD AS A DUTY OF THE LIVING

Perhaps a feeling of duty drives Prince Hamlet to visit with an apparition he believes is the ghost of his father, and later, drives him to mistakenly kill Polonius, and eventually kill his uncle.

A similar feeling of duty drives the three queens in The Two Noble Kinsmen to seek the help of Theseus.

A duty to honor their dead king seems to drive the people of Thebes and Oedipus to find the king’s murderer in spite of warnings from the blind seer, Tiresias.

And a sense of duty to honor both of her dead brothers drives Antigone to oppose her uncle’s order and try to retrieve and bury her brother’s body, risking her life and sacrificing her future as queen of the city.

We feel a duty toward the dead, in part due to the fact that, regardless of their virtues or vices, we often owe them our very lives: This includes not only parents to whom we owe our conception and birth, but also teachers, mentors, colleagues, friends, lovers, family, neighbors, and even strangers, and people now long-dead.

In ways of which we are never fully aware, we owe one another our daily bread, our sustenance and continued existence.

As Albert Einstein observed,

So our lives are mutually contingent in mysterious ways, and we owe more debts than we could ever repay. And these are a few of the many reasons why we feel moved to honor the dead, and why cultures create rituals that recognize the many gifts and contingencies that sustain our lives in mysterious ways, and honor the mystery and its transcendence as well. We don’t have to believe in a god for this to be the case. It is simply the reality of existence.

WHEN THE DEAD DISHONORED THEMSELVES IN LIFE

But the strange thing about Hamlet, and the Oedipus cycle by Sophocles, is that these stories all involve people claiming that the dead have been dishonored, when in fact the dead have often dishonored themselves: Hamlet’s father is in purgatory for some sin, having died “full of bread,” comfortable while others suffered; his skin is made “Lazar-like” by a brother’s poison, a reference to the gospel story of “The Rich Man and Lazarus,” the neglected beggar who went to heaven while the selfish rich man went to hell.

Laius, King of Thebes, has been killed but his murderer has not been found, so a plague grips the city, oppressed by the Sphinx with a riddle to solve. The king has not been properly honored in death because his killer is still on the loose, but in fact the king had lived quite dishonorably: When he was young, he was given sanctuary by another king, but Laius raped the host king’s son. When Laius heard a prophecy that his own son would one day grow up to kill him and marry his wife, Laius had his infant son abandoned in the wild, tied in place through his pierced ankles, to die of the elements. What honor is there in such choices? Laius was killed on the road for his hubris & violence by a stranger who happened to be the returning son who never knew him. If Laius had lived a better life and made more honorable choices, he might have been spared a dishonorable death. Scholars like to claim this and that about the imperative of honoring the dead in the case of Laius, but many neglect the way Laius had dishonored himself.

The brothers of Antigone fared no better. Polynices had been the older brother, but Eteocles gained popular support to rule Thebes. By one account, Eteocles simply expelled his brother; by another, the brothers had agreed that they would share rule and take turns on the throne, but Eteocles would not give up the throne when the time came. So Polynices gathered forces to oppose his brother. The brothers killed one another. Their uncle Creon, who ruled after they died, decreed that Eteocles (who had been king, but who dishonorably refused to give up the throne when his time had ended) should be honored in burial, but that the rightful challenger, Polynices, should be left unburied, and for his corpse to rot and be eaten by carion. Those who violated Creon’s decree were to be killed. Perhaps both brothers lived dishonorably, to argue and kill for the throne.

Maybe King Hamlet should have lived more honorably instead of sinfully, dying “full of bread,” like the rich man in the Lazarus tale; maybe he should have tried harder to discern his brother’s talents and win his friendship instead of his enmity and envy. Maybe he should have tried to win the friendship of Fortinbras as an ally instead of killing him in single combat on the day Prince Hamlet was born. If he had lived more honorably, maybe his wife, brother, and neighboring Norway would have been more inclined to honor him in death.

If Laius had not, in his youth, raped his host king’s son, if he had not abandoned his own son to die, if he had not displayed such hubris and violence toward a stranger on the road, maybe he would not have been killed by an estranged son who could not recognize him.

If Eteocles and Polynices had shared the throne and honored their agreement, or if Polynices had not raised an army against his brother, maybe they could have lived longer in peace. If Creon had not been so stubborn about putting Antigone to death for attempting to bury her brother, maybe Creon’s son and wife would not have committed suicide.

Antigone’s conviction seems to be that even the apparently dishonored (or disobedient) should be given traditional burial rites. Both Eteocles and Polynices should be honored in death, regardless of how honorably or dishonorably they lived. (I tend to agree with Antigone, and to respect the risks she took in disobeying her uncle’s decree).

This may be true of Laius and King Hamlet as well. Although they dishonored themselves at times in life, our task of honoring all in death is another matter. Better for us to be generous than to judge too harshly.

THE STANDARD BY WHICH WE MEASURE OTHERS WILL BE USED TO MEASURE US

In Hamlet, the prince asks Polonius to make sure the players are well-taken-care-of:

So perhaps we should honor all the dead, for to judge otherwise and to fail in this, we dishonor ourselves and end up at war with our own shadows. A Hamlet claims, “the less they deserve, the more merit is in your bounty. Take them in.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In the past, I have reminded readers that Shakespeare's Globe Theater in London has been offering free viewing of certain productions during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, while many are staying home and social distancing. Each play has been made available on Youtube for two weeks, starting with Hamlet and then The Two Noble Kinsmen.

Starting yesterday, Monday, 18 May through Sunday 31 May, the new play that can be viewed for free from this link is Shakespeare's A Winter's Tale. You can also view it directly on YouTube here during this same time period.

To donate to Shakespeare's Globe, click here.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Quotes from Hamlet are taken from InternetShakespeare, Modern, Editor's Version, edited by David Bevington, and courtesy of the University of Victoria in Canada.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Disclaimer: By noting bible passages in this blog, I do not intend to promote any religion over any other, nor am I attempting to promote religious belief in general; only to point out how the Bible may have influenced Shakespeare, his plays, and his age.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading!

My current project is a book tentatively titled Hamlet’s Bible, about biblical allusions and plot echoes in Hamlet.

Below is a link to a list of some of my top posts (“greatest hits”), including a description of my book project (last item on the list):

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2019/12/top-20-hamlet-bible-posts.html

I post every week, so please visit as often as you like and consider subscribing.

In The Two Noble Kinsmen, three queens complain that their husbands have been dishonored by being left unburied after battle, echoing a theme from Antigone in the Oedipus cycle. In Hamlet, the prince feels his mother and uncle have dishonored his dead father by not mourning long enough, and by what would have been considered a biblically incestuous marriage in Shakespeare’s England. Honoring the dead was a duty both plays assumed it would be wrong to neglect.

[Paapa Essiedu as Hamlet with the skull of Yorick in a 2016 RSC production. Photo via TheShakespeareBlog.com.]

OLD SCHOOL

Yet it’s strange to note how, in Hamlet criticism and in commentary on the Oedipus cycle, the predominantly male scholars and critics before 1960 tended to focus relatively little upon the sins of King Hamlet that landed him in purgatory; many assumed he was mostly a great and honorable king who had been dishonored in death by his brother and wife.

- Critics usually took Hamlet at his word, that his father was a goodly king.

- They often took Old Norway at his word, that Young Fortinbras had been scolded and his aggression successfully redirected toward Poland.

- One would think that, in Protestant England, more commentary would have assumed the ghost was from hell, a demon disguised as the dead king, sent to damn the prince; yet a surprising majority seem to have taken the ghost at his word, that he was only temporarily suffering while his sins were purged away.

G.R. Elliott’s 1951 book, Scourge and Minister (Duke University Press) is representative of this kind of approach, tending to place great trust in patriarchal authorities even when the evidence of the texts suggests flaws that may render kings untrustworthy.

Even Freudian criticism, from the start, has tended to focus more on the assumed dysfunction in the son (an “Oedipal complex”) than on the failings and dysfunctions of a distant, neglectful, and violent father.

The religious commentary of Roy Battenhouse went so far as to suggest that Claudius was not so bad a king, thinking him an able administrator (?!) and perhaps the best and most Christian thing for Prince Hamlet to have done for his own sake and that of Denmark would have been to forgive him, bide his time, and eventually assume the throne upon Claudius’ death. It would seem that, in the view of Battenhouse, personal piety as a cover for ambition and a path to salvation was more important than for princes to be champions of justice, if that meant opposing patriarchal authorities, which Battenhouse seemed disinclined to support (a traditional Christian argument based on passages from the letters of St. Paul regarding obedience to earthly authorities).

When Sophocles’ Oedipus cycle was taught in previous generations, students were often told that the visitation of the Sphinx and plague had been caused not by the injustices or bad karma of Laius, but by blind action of Oedipus, who unknowingly killed his father. The point seemed to be only that the murderer of the father had to be brought to justice, to the great shame of the son, rather than that a destructive and abusive man, father, and king, Laius, had himself been a plague, and the dysfunctional family needed to be confronted and stopped.

When Antigone was taught, the focus was often upon the stubbornness and pride of Antigone instead of upon the poor decisions of Creon or Antigone’s brothers. Instructors often claimed that the outlook of the Oedipus cycle’s original audiences was focused upon how all lives are ruled by fate. So in spite of a great deal of evidence of the flaws of men, perhaps the play was taught by men in such a way as to keep women in their place: Antigone, for all her good intentions, should not have disobeyed Creon’s decree. To paraphrase a contemporary meme, “This is why we can’t have good things: Women are unwilling to respect the authority of men.”

WHAT CHANGED?

So what changed, to make scholars have a greater tendency to consider the flaws or sins of men and kings, and to let the texts inspire more questions than easy answers? Was it the hiring of more women and people of color in English departments and the humanities? Or did the same social forces that led to these changes in hiring practices also encourage even white men to ask better questions about the texts? Perhaps both.

But now it is quite alright to ask at length about those sins that brought King Hamlet to purgatory in the first place, his violence toward Old Fortinbras that left Young Fortinbras without a father, his neglect of his son, the prince, and perhaps his neglect of his wife while he was off proving himself through violence. It is OK to ask if perhaps Old Norway was dissembling about his harsh words with his nephew, the financing of an army to go against Poland, and the humble plea for permission to march across Denmark on the way to Poland; perhaps all of that was to hide an attack that had been intended for Denmark all along.

HONORING THE DEAD IN A TIME OF PANDEMIC

On the topic of honoring the dead properly: During the current pandemic, there have been many stories about families unable to observe traditional burial rites, often unable to claim the bodies of dead family members, stories from China, Italy, Spain, New York, Ecuador, Iran, India, and many other places.

A pandemic doesn’t care about the innocent or guilty, the wicked or the just. Sometimes it spares the proud and selfishly negligent, but claims the selfless and heroic. In recent months, many people all over the world have known of family, friends and neighbors who were unable to honor their dead with anything that resembled traditional mourning rituals. For some of the more privileged, this might mean having to watch funeral services remotely on video provided by a funeral home while observing stay-home requirements and social distancing. For others, it may mean that the stench of the dead hangs over their city while the dead go unclaimed.

Certainly the COVID-19 pandemic has traumatized populations, and perhaps it is moving, and will continue to move, scholars to ask new questions about literature like Hamlet and the Oedipus cycle, as we ponder what it means to honor the dead.

More than that, a pandemic has forced many to reimagine what it means to honor their beloved dead, often not only at a great distance from the body of the deceased, but also from other mourners. While this may be good for some, and a positive and creative endeavor, it undoubtedly is also a challenge that has left many others feeling empty and robbed of the sort of parting rituals they would have preferred. We often feel great personal need for mourning, but also a duty toward the dead, their legacy, and the world.

If you were to die during this pandemic, how would you want people to honor your life and death? By risking infection in a community funeral service, and perhaps causing more deaths? Or would you prefer for the living to find other ways to honor your legacy? (I would prefer the later.)

HONORING THE DEAD AS A DUTY OF THE LIVING

Perhaps a feeling of duty drives Prince Hamlet to visit with an apparition he believes is the ghost of his father, and later, drives him to mistakenly kill Polonius, and eventually kill his uncle.

A similar feeling of duty drives the three queens in The Two Noble Kinsmen to seek the help of Theseus.

A duty to honor their dead king seems to drive the people of Thebes and Oedipus to find the king’s murderer in spite of warnings from the blind seer, Tiresias.

And a sense of duty to honor both of her dead brothers drives Antigone to oppose her uncle’s order and try to retrieve and bury her brother’s body, risking her life and sacrificing her future as queen of the city.

We feel a duty toward the dead, in part due to the fact that, regardless of their virtues or vices, we often owe them our very lives: This includes not only parents to whom we owe our conception and birth, but also teachers, mentors, colleagues, friends, lovers, family, neighbors, and even strangers, and people now long-dead.

In ways of which we are never fully aware, we owe one another our daily bread, our sustenance and continued existence.

As Albert Einstein observed,

Strange is our situation here upon earth. Each of us comes for a short visit, not knowing why, yet sometimes seeming to a divine purpose. From the standpoint of daily life, however, there is one thing we do know: That we are here for the sake of other men —above all for those upon whose smile and well-being our own happiness depends, for the countless unknown souls with whose fate we are connected by a bond of sympathy. Many times a day, I realize how much my outer and inner life is built upon the labors of people, both living and dead, and how earnestly I must exert myself in order to give in return as much as I have received and am still receiving.A farmer plants a crop, machines or laborers pick it, and hundreds or thousands of miles away, we are able to eat. Or an ancient philosopher was able to eat, and one of their ideas helps us make an important decision, changing the course of our lives. A stranger was alert on the road instead of being distracted or falling asleep at the wheel, and we (or one of our ancestors) arrived home safely instead of being killed.

(from The World as I See It, 1934)

So our lives are mutually contingent in mysterious ways, and we owe more debts than we could ever repay. And these are a few of the many reasons why we feel moved to honor the dead, and why cultures create rituals that recognize the many gifts and contingencies that sustain our lives in mysterious ways, and honor the mystery and its transcendence as well. We don’t have to believe in a god for this to be the case. It is simply the reality of existence.

WHEN THE DEAD DISHONORED THEMSELVES IN LIFE

But the strange thing about Hamlet, and the Oedipus cycle by Sophocles, is that these stories all involve people claiming that the dead have been dishonored, when in fact the dead have often dishonored themselves: Hamlet’s father is in purgatory for some sin, having died “full of bread,” comfortable while others suffered; his skin is made “Lazar-like” by a brother’s poison, a reference to the gospel story of “The Rich Man and Lazarus,” the neglected beggar who went to heaven while the selfish rich man went to hell.

Laius, King of Thebes, has been killed but his murderer has not been found, so a plague grips the city, oppressed by the Sphinx with a riddle to solve. The king has not been properly honored in death because his killer is still on the loose, but in fact the king had lived quite dishonorably: When he was young, he was given sanctuary by another king, but Laius raped the host king’s son. When Laius heard a prophecy that his own son would one day grow up to kill him and marry his wife, Laius had his infant son abandoned in the wild, tied in place through his pierced ankles, to die of the elements. What honor is there in such choices? Laius was killed on the road for his hubris & violence by a stranger who happened to be the returning son who never knew him. If Laius had lived a better life and made more honorable choices, he might have been spared a dishonorable death. Scholars like to claim this and that about the imperative of honoring the dead in the case of Laius, but many neglect the way Laius had dishonored himself.

The brothers of Antigone fared no better. Polynices had been the older brother, but Eteocles gained popular support to rule Thebes. By one account, Eteocles simply expelled his brother; by another, the brothers had agreed that they would share rule and take turns on the throne, but Eteocles would not give up the throne when the time came. So Polynices gathered forces to oppose his brother. The brothers killed one another. Their uncle Creon, who ruled after they died, decreed that Eteocles (who had been king, but who dishonorably refused to give up the throne when his time had ended) should be honored in burial, but that the rightful challenger, Polynices, should be left unburied, and for his corpse to rot and be eaten by carion. Those who violated Creon’s decree were to be killed. Perhaps both brothers lived dishonorably, to argue and kill for the throne.

Maybe King Hamlet should have lived more honorably instead of sinfully, dying “full of bread,” like the rich man in the Lazarus tale; maybe he should have tried harder to discern his brother’s talents and win his friendship instead of his enmity and envy. Maybe he should have tried to win the friendship of Fortinbras as an ally instead of killing him in single combat on the day Prince Hamlet was born. If he had lived more honorably, maybe his wife, brother, and neighboring Norway would have been more inclined to honor him in death.

If Laius had not, in his youth, raped his host king’s son, if he had not abandoned his own son to die, if he had not displayed such hubris and violence toward a stranger on the road, maybe he would not have been killed by an estranged son who could not recognize him.

If Eteocles and Polynices had shared the throne and honored their agreement, or if Polynices had not raised an army against his brother, maybe they could have lived longer in peace. If Creon had not been so stubborn about putting Antigone to death for attempting to bury her brother, maybe Creon’s son and wife would not have committed suicide.

Antigone’s conviction seems to be that even the apparently dishonored (or disobedient) should be given traditional burial rites. Both Eteocles and Polynices should be honored in death, regardless of how honorably or dishonorably they lived. (I tend to agree with Antigone, and to respect the risks she took in disobeying her uncle’s decree).

This may be true of Laius and King Hamlet as well. Although they dishonored themselves at times in life, our task of honoring all in death is another matter. Better for us to be generous than to judge too harshly.

THE STANDARD BY WHICH WE MEASURE OTHERS WILL BE USED TO MEASURE US

In Hamlet, the prince asks Polonius to make sure the players are well-taken-care-of:

HAMLET: Good my lord, will you see the players well bestowed? Do ye hear, let them be well used, for they are the abstracts and brief chronicles of the time. After your death you were better have a bad epitaph than their ill report while you live.This seems related to Antigone, and to the honorable burial of even the dead who dishonored others and themselves in life. If our lives truly are mysteriously contingent upon those of others, and if we are honest, we, too, have made mistakes and acted dishonorably; embracing even (and especially?) the flawed and questionable lives of the dishonored dead, we may embrace our own shadows. How can we know what causes or circumstances drove others to bad acts? How can we be sure that certain circumstances would not have done the same to us?

POLONIUS: My lord, I will use them according to their desert.

HAMLET: God's bodykins, man, much better. Use every man after his

desert and who should scape whipping? Use them after your own honor and dignity; the less they deserve, the more merit is in your bounty. Take them in. (2.2.1563-73)

So perhaps we should honor all the dead, for to judge otherwise and to fail in this, we dishonor ourselves and end up at war with our own shadows. A Hamlet claims, “the less they deserve, the more merit is in your bounty. Take them in.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In the past, I have reminded readers that Shakespeare's Globe Theater in London has been offering free viewing of certain productions during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, while many are staying home and social distancing. Each play has been made available on Youtube for two weeks, starting with Hamlet and then The Two Noble Kinsmen.

Starting yesterday, Monday, 18 May through Sunday 31 May, the new play that can be viewed for free from this link is Shakespeare's A Winter's Tale. You can also view it directly on YouTube here during this same time period.

To donate to Shakespeare's Globe, click here.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Quotes from Hamlet are taken from InternetShakespeare, Modern, Editor's Version, edited by David Bevington, and courtesy of the University of Victoria in Canada.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Disclaimer: By noting bible passages in this blog, I do not intend to promote any religion over any other, nor am I attempting to promote religious belief in general; only to point out how the Bible may have influenced Shakespeare, his plays, and his age.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading!

My current project is a book tentatively titled Hamlet’s Bible, about biblical allusions and plot echoes in Hamlet.

Below is a link to a list of some of my top posts (“greatest hits”), including a description of my book project (last item on the list):

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2019/12/top-20-hamlet-bible-posts.html

I post every week, so please visit as often as you like and consider subscribing.

Comments

Post a Comment