Hamlet's Warrior-Christian Dialectic

Two weeks ago, my blog post mentioned Paul A. Cantor’s insightful introduction to the Cambridge University Press Hamlet (2004, 2012), including his use of Hegel's idea of Tragedy as conflicting ideas of the good. Cantor also does a good job not only identifying the importance of both Christian and classical allusions, but also of noting that Christian and Classical worldviews are in an uncomfortable dialectic in the play.

[Paul A. Cantor, image from screenshot, Youtube]

In act 1, scene 2, Claudius describes Denmark not as a Christian state, but a "warlike state." The classical code of honor and revenge is demonstrated by the ghost's commission that Hamlet avenge his murder, and also by the first performance of a speech by the players about the story of Hecuba witnessing Pyrrhus's revenge on Priam. Christianity is demonstrated at many turns in the play, with allusions and plot echoes, from Horatio as the doubting Thomas of the first scene, to the very last scene and his English translation of a line from the requiem mass (and also from the gospel tale of Lazarus and the Rich Man), "May flights of angels sing thee to thy rest." The contrast between the classical warrior-honor code and Christianity's central teachings helps create some of the tension in the play.

From page 3 of Cantor's introduction:

Cantor continues:

"One can see how difficult it is to fuse Christianity and Classicism if one looks at the concept of heroism in the two traditions. The Achilles of Homer's Iliad is the classical hero par excellance, and it would be hard to imagine a less Christian figure. Achilles is proud, aggressive, vengeful, exulting in his power, and implacable in his enmity."

Sounds like the ghost of Hamlet's father.

Later, he notes,

"The answer a number of Renaissance authors found to the dilemma of how to combine an epic celebration of partial heroism with Christian principles was the idea of a crusade. If a noble hero could be shown battling on behalf of Christianity against pagan enemies, then whatever ferocity he displayed would have a religious justification. He would be fighting not on behalf of his country - or at least not merely [that,] but on behalf of the one true faith and thus fro the sake of eternal glory and salvation." Cantor cites Aristo's Orlando Furioso (1516), Tasso's Liberata (1575), and Spenser's The Fairie Quenne (1590, 1596) as examples.

Yet in these examples, it seems the warrior wins out in the dialectic with the Christian, discarding the gospel command to love one's enemies.

OLDER EXAMPLES OF CHRISTIAN-CLASSICAL DIALECTICS

In some ways, the idea of Christian-Classical dialectics were not new by Shakespeare's time: St. Augustine is viewed as having been influenced by Plato (Stephen Greenblatt explored some of Plato's influence on Augustine in a 2017 New Yorker article, "How St. Augustine Invented Sex"); and centuries later, St. Augustine sought to synthesize many Christian ideas with Aristotelian thought, something that was actually controversial at the time, as some believed Christianity would be corrupted in the process.

Yet Shakespeare was not writing theology, but drama; the dialectic was between the poems, stories, and dramas from classical writers, often involving heroism, honor, and revenge, as compared to the Christian story, which has different dynamics.

THE GHOST: FAILED DIALECTIC

The Ghost demonstrates a very unsuccessful dialectic of the Classical idea of the hero/warrior-king, contrasted with the Christian. The dead king was considered good for his bravery and heroism in battle, yet the ghost says he died having committed "foul crimes." He is not so different from many other monarchs who enjoyed the right of conquest, and then used the law to dress up his pirate-like crimes and make them appear more legitimate. So instead of speaking of his sins, naming what exactly these "foul crimes" were and how he failed to live as a good Christian, he speaks only of the legalistic technicality of being killed without having confessed his sins, without having been granted forgiveness, without having received the last rites and holy communion, as if these sacramental technicalities could have fixed the problem of his foul crimes.

The ghost illustrates a failure as a Christian, whether he is a demon in disguise or a ghost from purgatory. His warrior-king self was too strong, so in his dialectic with Christianity, Christian teachings have had little effect, and had failed to make him stop and reconsider his life and repent of his sins.

In many ways, the ghost is a typical monarch of the period. Law said monarchs have a right of conquest in lands they conquer. But Christianity says "Love your enemy," and "Turn the other cheek," and "Vengeance is mine, says the Lord." They don't mix well.

HAMLET'S DIALECTIC

The dialectic that the ghost failed at, between his warrior-self and his Christian self, is the one his son Hamlet engages in much more in earnest.

The famous speech, "To be or not to be," is about being on the knife-edge of such a dialectic:

To suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune?

Or to take up arms against a sea of troubles?

To act perhaps like a loving, patient and forgiving Christian, suffering all?

Or perhaps doing so only to buy time, in the hope of outliving Claudius and becoming king?

To take up arms - against Claudius - and end his troubles by... becoming a king-killer, like Claudius, and perhaps being executed as a murderer?

Or to die in the process of fighting Claudius, as the sons of Oedipus died fighting each other?

Or if rooting out what is rotten in Denmark is too much, perhaps to give up and commit suicide?

But in so doing, perhaps to find a worse eternal fate?

When his warrior-king father entered the dialectic with Christianity, the warrior king won, and the hope of his becoming more Christian lost. Hamlet engages more earnestly in the dialectics, but in the most sloppy way: The specter of his father suffering in purgatory makes him fearful of his own tendencies to sin, so he treats Ophelia and her beauty as things that would only tempt him toward damnation. Not the most Christian thing to do. He assumes it's Claudius behind the arras, and perhaps heaven and hell have sanctioned his revenge; but no, it's Polonius, who he kills by accident. Sloppy, not Christian. He later assumes that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern know the contents of the letter from the king, so he changes the letter to order his friends' deaths instead of his own. Also sloppy work on this point. He says he will "answer" later for the death of Polonius, but to Horatio he claims, like a king with right of conquest, that the deaths of his friends don't touch his conscience. This is not very Christian at all.

Yet he feels Providence has saved him at sea with the help of pirates, and in the graveyard, he receives a gift of remembrance of the affection that the court jester Yorick once showed him. He feels God has been merciful to him, so he becomes more aware of his mistakes, and prepares to be more merciful and apologetic toward Laertes. The warrior-Christian dialectic his father failed at so abysmally is now something the prince is slightly more adept at.

THE CHRISTIAN-WARRIOR DIALECTIC PHRASED AS A JOKE

"St. Francis and Genghis Khan walk into a bar....

Who wins?"

Well, as the bible and a certain Flannery O'Connor title say, "The Violent Bear It Away."

In the larger biblical context, the phrase comes from Matthew 11:12; in Shakespeare's time, the 1599 bible put it this way:

And from the time of John Baptist hitherto, the kingdom of God suffereth violence, and the violent take it by force.

John the Baptist and many other prophets were killed; the violent take things by force, they "bear it away."

Or perhaps as Flannery O'Connor's Catholic Douay-Rheims translation put it: "And from the days of John the Baptist until now, the kingdom of heaven suffereth violence, and the violent bear it away."

NO JOKE

Even asking the question of who wins between St. Francis and Genghis Khan implies we are thinking more like Genghis Khan than like St. Francis. The monk Francis was famous for taking seriously the gospel command to love one's enemies, even meeting with the Sultan of Egypt during the 5th Crusade.

The warrior may think he wins (according to warrior standards) if he kills, or fights and wins against St. Francis.Then it's not a dialectic, but just violence.

Francis wins if he is more kind and patient, more willing to listen, to open his mind and heart to the other, more willing to act as a servant. Francis wins if, like Jesus, he speaks the truth, acts in love, and perhaps in some situations, is willing even to die, or in others, willing to be changed.

So the Christian who engages in an open-minded, open-hearted dialectic is perhaps acting most Christian (paradoxically) if she or he is willing to listen and learn and be changed by the other. The same Christianity that counsels love of enemies and welcome to strangers bids the Christian to enter into fruitful dialectics, not only with friends and family, but perhaps especially with strangers and enemies. This is not required of the warrior (although, for example, Sun Tsu's The Art of War would counsel the warrior to learn from enemies, or at least metaphorically to allow one's enemies to be one's teachers).

SOMETHING ROTTEN IN CHRISTIANITY AFTER CONSTANTINE

Many have noted that the Christians of the early church may have acted more in harmony with the gospel than it seems Christianity did after the conversion of Constantine and the militarization of Christianity in kingdoms, in a "holy" Christian empire set to conquer new lands and claim them for Christ, the "prince of peace."

Too often, it seems that in the warrior-Christian dialectic, the warrior won.

We can see this in part in the Roman Catholic Church's "Doctrine of Discovery," made up of papal bulls that encouraged Christian explorers and armies to seek out and subdue aboriginal people in distant lands. As noted in a 2015 article in The Conversation, one of these bulls encouraged Christians

"...to invade, search out, capture, vanquish, and subdue all Saracens and pagans…the kingdoms, dukedoms, principalities, dominions, possessions, and all movable and immovable goods…held and possessed by them."

Christianity in the USA is still plagued in this way, with Christian warriors and evangelists seeking to win "victories for Jesus" against strangers whose culture and religion are different. Too many of them assume that spreading American military empire and capitalism is the same as spreading Christianity.

This is evident in complaints and tensions in the US armed forces, where military leaders pressure soldiers to attend evangelical meetings, a problem that surfaced during the 2003 war in Iraq, and still persists, as demonstrated in violation of rules reported in August of 2018. The warriors are winning, and subduing Christianity to act in service of war and military empire.

THE WAY THE HAMMER SHAPES THE HAND

The danger of any dialectic is that something essential may be lost if one side gives in too much to the other. Instead of Christians recognizing some things about warrior culture that must be rejected as incompatible, more often, Christianity has been assimilated and subjugated to serve the goals of warrior culture. The Christian who takes up weapons of war will be changed by those weapons, "the way the hammer shapes the hand," in the words of songwriter Jackson Browne. His song, "Casino Nation," explores this relationship:

In a weapons producing nation under Jesus

In the fabled crucible of the free world

Camera crews search for clues amid the detritus

And entertainment shapes the land

The way the hammer shapes the hand

Gleaming faces in the checkout counter at the Church of Fame

The lucky winners cheer Casino Nation

All those not on TV

Only have themselves to blame

And don't quite seem to understand

The way the hammer shapes the hand

Out beyond the ethernet the spectrum spreads

DC to daylight, the cowboy mogul rides

Never worry where the gold for all this glory's gonna come from

Get along dogies, it's coming out of your hides

The intentional cultivation of a criminal class

The future lit by brightly burning bridges

Justice fully clothed to hide the heart of glass

That shatters in a thousand Ruby Ridges

And everywhere the good prepare for perpetual war

And let their weapons shape the plan

The way the hammer shapes the hand

Lyrics by Jackson Browne, 2002

Hamlet's way of thinking about his position as disappointed prince and as son of a murdered king is necessarily influenced by his idolizing of a warrior-king father whose ghost (he believes) has asked him to avenge his murder. The hammer of royal power and warrior status has already shaped the hand of the prince. But thoughts of his eternal fate and Christian teachings tug him in other directions.

EISENHOWER'S WARNING

President Dwight Eisenhower, formerly a general who had served in Europe in World War II, was a fiscal conservative. It annoyed him to watch congress approve many unnecessary programs for military spending that would create jobs in many states and thereby assist incumbent representatives and senators in being reelected. He knew that, if the US was constantly approving the production of weapons and supplies for war, and if there was so much profit to be made from war, we would probably become a nation that would be more inclined to seek military conflicts. The hammer of more military weapons would shape the hand of a nation whose founders warned against entanglements in foreign wars, but which increasingly had ignored the advice of its founders.

In his "Chance for Peace" speech after the death of Stalin in 1953, drawing upon biblical phrases and Christian imagery, Eisenhower is famous for having said,

Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed.

This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children. The cost of one modern heavy bomber is this: a modern brick school in more than 30 cities. It is two electric power plants, each serving a town of 60,000 population. It is two fine, fully equipped hospitals. It is some fifty miles of concrete pavement. We pay for a single fighter with a half-million bushels of wheat. We pay for a single destroyer with new homes that could have housed more than 8,000 people. . . . This is not a way of life at all, in any true sense. Under the cloud of threatening war, it is humanity hanging from a cross of iron.

Eisenhower viewed the death of Stalin as an opportunity to reach arms agreements, end the cold war, and redirect monies that had been used for military spending toward meeting humanitarian needs. But this was not to be.

As a younger man, Eisenhower had been present on the capital mall when the "Bonus Army" gathered there during the depression years, a gathering of veterans who had been promised bonus pay after service in World War I, "The Great War" that had been said would end all wars. Marine Major General Smedley Butler had been a supporter of the veterans' demands and spoke to them on the mall. Butler had written a book, War is a Racket, which claimed that many US military engagements around the world were not to advance good will and democracy, but to advance the profits of large business interests. Eisenhower may have been influenced a bit by Butler's ideas later as he shaped his farewell speech, warning of the "military-industrial complex" (a phrase that had originally been, "military-industrial-congressional complex").

Eisenhower's warnings went largely unheeded. John Kennedy sought to end involvement in Vietnam and to enter into a variety of nuclear treaties, including the banning of above-ground nuclear tests. His generals wanted to fight and win a war against the Soviet Union, But Kennedy was assassinated, some believe, for his plans to pull out of Vietnam and for being perceived as too weak with the Soviets. As Jackson Browne notes, "In a weapons-producing nation under Jesus," the hammer of weapons had become too powerful in shaping the hand.

POLONIUS & REP. TED YOHO, SUGARING O'ER DEVILS WITH DEVOTION'S IMAGE

In Shakespeare's Hamlet, Polonius gives Ophelia a prayer book and wants her to read it when she first sees the prince in act 3, scene 1. Polonius says,

We are oft to blame in this,

'Tis too much prov'd, that with devotion's visage

And pious action we do sugar o'er

The Devil himself.

This is another example of failed dialectics, when the image of religiosity is used to serve dishonest purposes. We saw something like this just this past week, when Rep. Ted Yoho (R-Florida) accosted Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez on the capital steps, calling her "disgusting" and a"fucking bitch" for suggesting some people steal because they are hungry. Later, in a non-apology, Yoho said "I rise to apologize for the abrupt manner of the conversation I had with my colleague from New York...The offensive name calling words attributed to me by the press were never spoken to my colleagues." In other words, he apologizes only for abruptness, not for calling AOC names that a reporter overheard. Yoho added, " “I cannot apologize for my passion, or for loving my God, my family, and my country.”

So Yoho sugars o'er the devil by denying he used the offensive language, and claiming his abruptness was motivated in part by his love of God.

Again, in the warrior-Christian dialectic, the warrior clearly has won in Yoho, and the ostensibly Christian language is subordinated to serve the goals of the warrior.

Yoho resigned from the board of a Christian organization, perhaps under pressure after his uncivil remarks. Author David Talbot (The Devil's Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the Rise of America's Secret Government) had an appropriate and humorous brief comment about Yoho's resignation:

But in a larger context, Yoho inadvertently highlighted AOC in the role of the Christian victim, taking the side of the poor and imprisoned, and being made to suffer in public for it. Rebecca Traister does a good job exploring how the exchange between Yoho and AOC fits into a larger context of "gendered power imbalance in political, public, and personal life." (Many thanks to Emanuela Zanchi for sharing a link to Traister's essay.)

WARRIOR-CHRISTIAN DIALECTICS AND INTELLECTUAL COLONIZATION

Perhaps we see another example of the warrior-conqueror winning out in the warrior-Christian dialectic in instances of intellectual colonization. We often hear teachers claim that they learn more from their students in the long run than students learn from them. At best, this may be evidence of teachers who are open to two-way dialectics with their students, allowing the students to provide new insights. But at worst, some teachers may say this, but still practice a form of intellectual colonization, where the teacher has all the answers and the students must be subjugated by the teacher's superior ideas. In a larger sense, citizens of many nations are considering ways that the effects of colonial rule have persisted even after colonial rulers have left; persisted through the effects of the colonizer's language and ideas. Many resources explore and debate this. For just a few examples:

- ResearchGate.net has an interesting PDF of a paper on the effects of a Commonwealth adult education program, asking whether it actually liberates, or perhaps is an example of intellectual colonialism.

- In India, some have noted that the English language has intellectual-colonizing effects and propose the importance of Indian scientists and academics writing in their first languages, while others claim that this "would be disasterous."

- In a 2007 essay, "Imperialist Democracy, Intellectual Colonialism," by Hassan Tahsin, the author points out a variety of important concerns.

If a colonizer claims to want to save a culture and a people by introducing western values, the hidden motive is often access to resources and profit. This is more the warrior-conqueror at work, and if we are to call it Christian, it's the version of Christianity that has already been made rotten by its dialectics with warrior-conqueror empires.

MORE RESOURCES

Much has been written about classical allusions in Shakespeare, including Hamlet; Professor Philip Allingham of Lakehead University in Canada has a good web page that serves as an introduction to classical allusions in the play. For those new to my blog, for more on the presence of biblical allusions, see Naseeb Shaheen's book, Biblical References in Shakespeare's Plays (2011), and for plot echoes, consider viewing my list of "greatest hits" (best and most popular blog posts about biblical plot echoes in Hamlet).

For those interested in more from Paul A. Cantor, he has a series of three lectures on YouTube that you may find of interest:

- Hamlet (1 of 3)

[In this video, Cantor mentions "Renaissance man" and what an "early modern man" would think of as a Renaissance man; he pauses because he knows it's sexist, but then he prefers it anyway for how it sounds. Cantor is an older scholar, so this is the language he uses; it's a limitation, but there are still many gems in the videos.

- He also mentions around 6:00 the year 1453 and the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman turks as a turning point, where fleeing scholars brought to the west ancient texts they had heard of but not known, leading to a kind of golden age.

- He speaks of the Aristotelia virtues contrasted with the Christian virtues, and how these surface in interesting combinations in visual art and in poetry such as Spencer's Fairie Queen.

- Later (15:41), he notes that, typically, the virtues (Aristotelian) that make you succeed in war will not help you succeed in peace.- Around 23:00 he mentions the stark contrast between Laertes, who upon hearing of his father's death will not let Christianity or damnation stand in the way of his revenge, in stark contrast with Hamlet. So as a foil, Laertes is not merely more a man of action than Hamlet as many note, but he is also much less concerned with his eternal fate, as also later shown by his remark about cutting Hamlet's throat in the church.

- Around 26:00, he speaks of Horatio as a different sort of foil, a stoic (but perhaps a stoic would not allow himself to be swayed, changed in a fruitful dialectic?)

- 31:20, comments on sending Rosencrantz & Guildenstern to their deaths, "not shriving time allowed" (as the ghost claimed to have none allowed for him) - and Hamlet acting like a man of action instead of a melancholic.

- 32:45, Hamlet as a political and ambitious man.]

- Hamlet (2 of 3)

- Hamlet (3 of 3)

For those interested in more of my work on dialectics between characters in Hamlet, I discuss this by another name: Gift dynamics, or "labors of gratitude," where characters say and/or do things that become like gifts, which influence other characters in a larger matrix of dialectics. You can read more of my thoughts on these dialectics in a series of posts: I presented a paper on this just this year (a Zoom meeting version of our Shakespeare Association of America seminar), described in the following post (SAA Seminar: “Shakespeare & the Mind: Cognition, Emotion, Affect").

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Disclaimer: If and when I quote or paraphrase bible passages in many of my blog posts, I do not intend to promote any religion over any other, nor am I attempting to promote religious belief in general; only to point out how the Bible may have influenced Shakespeare, his plays, and his age.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading!

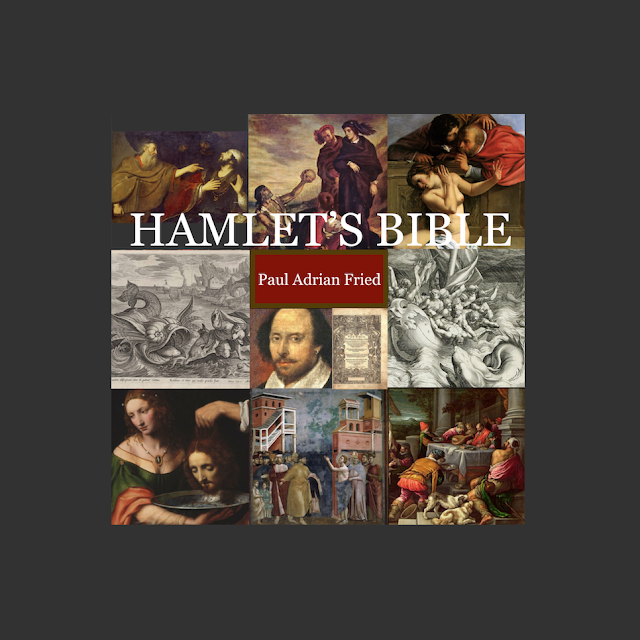

My current project is a book tentatively titled Hamlet’s Bible, about biblical allusions and plot echoes in Hamlet.

Below is a link to a list of some of my top posts (“greatest hits”), including a description of my book project (last item on the list):

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2019/12/top-20-hamlet-bible-posts.html

I post every week, so please visit as often as you like and consider subscribing.

[Paul A. Cantor, image from screenshot, Youtube]

In act 1, scene 2, Claudius describes Denmark not as a Christian state, but a "warlike state." The classical code of honor and revenge is demonstrated by the ghost's commission that Hamlet avenge his murder, and also by the first performance of a speech by the players about the story of Hecuba witnessing Pyrrhus's revenge on Priam. Christianity is demonstrated at many turns in the play, with allusions and plot echoes, from Horatio as the doubting Thomas of the first scene, to the very last scene and his English translation of a line from the requiem mass (and also from the gospel tale of Lazarus and the Rich Man), "May flights of angels sing thee to thy rest." The contrast between the classical warrior-honor code and Christianity's central teachings helps create some of the tension in the play.

From page 3 of Cantor's introduction:

Cantor continues:

"One can see how difficult it is to fuse Christianity and Classicism if one looks at the concept of heroism in the two traditions. The Achilles of Homer's Iliad is the classical hero par excellance, and it would be hard to imagine a less Christian figure. Achilles is proud, aggressive, vengeful, exulting in his power, and implacable in his enmity."

Sounds like the ghost of Hamlet's father.

Later, he notes,

"The answer a number of Renaissance authors found to the dilemma of how to combine an epic celebration of partial heroism with Christian principles was the idea of a crusade. If a noble hero could be shown battling on behalf of Christianity against pagan enemies, then whatever ferocity he displayed would have a religious justification. He would be fighting not on behalf of his country - or at least not merely [that,] but on behalf of the one true faith and thus fro the sake of eternal glory and salvation." Cantor cites Aristo's Orlando Furioso (1516), Tasso's Liberata (1575), and Spenser's The Fairie Quenne (1590, 1596) as examples.

Yet in these examples, it seems the warrior wins out in the dialectic with the Christian, discarding the gospel command to love one's enemies.

OLDER EXAMPLES OF CHRISTIAN-CLASSICAL DIALECTICS

In some ways, the idea of Christian-Classical dialectics were not new by Shakespeare's time: St. Augustine is viewed as having been influenced by Plato (Stephen Greenblatt explored some of Plato's influence on Augustine in a 2017 New Yorker article, "How St. Augustine Invented Sex"); and centuries later, St. Augustine sought to synthesize many Christian ideas with Aristotelian thought, something that was actually controversial at the time, as some believed Christianity would be corrupted in the process.

Yet Shakespeare was not writing theology, but drama; the dialectic was between the poems, stories, and dramas from classical writers, often involving heroism, honor, and revenge, as compared to the Christian story, which has different dynamics.

THE GHOST: FAILED DIALECTIC

The Ghost demonstrates a very unsuccessful dialectic of the Classical idea of the hero/warrior-king, contrasted with the Christian. The dead king was considered good for his bravery and heroism in battle, yet the ghost says he died having committed "foul crimes." He is not so different from many other monarchs who enjoyed the right of conquest, and then used the law to dress up his pirate-like crimes and make them appear more legitimate. So instead of speaking of his sins, naming what exactly these "foul crimes" were and how he failed to live as a good Christian, he speaks only of the legalistic technicality of being killed without having confessed his sins, without having been granted forgiveness, without having received the last rites and holy communion, as if these sacramental technicalities could have fixed the problem of his foul crimes.

The ghost illustrates a failure as a Christian, whether he is a demon in disguise or a ghost from purgatory. His warrior-king self was too strong, so in his dialectic with Christianity, Christian teachings have had little effect, and had failed to make him stop and reconsider his life and repent of his sins.

In many ways, the ghost is a typical monarch of the period. Law said monarchs have a right of conquest in lands they conquer. But Christianity says "Love your enemy," and "Turn the other cheek," and "Vengeance is mine, says the Lord." They don't mix well.

HAMLET'S DIALECTIC

The dialectic that the ghost failed at, between his warrior-self and his Christian self, is the one his son Hamlet engages in much more in earnest.

The famous speech, "To be or not to be," is about being on the knife-edge of such a dialectic:

To suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune?

Or to take up arms against a sea of troubles?

To act perhaps like a loving, patient and forgiving Christian, suffering all?

Or perhaps doing so only to buy time, in the hope of outliving Claudius and becoming king?

To take up arms - against Claudius - and end his troubles by... becoming a king-killer, like Claudius, and perhaps being executed as a murderer?

Or to die in the process of fighting Claudius, as the sons of Oedipus died fighting each other?

Or if rooting out what is rotten in Denmark is too much, perhaps to give up and commit suicide?

But in so doing, perhaps to find a worse eternal fate?

When his warrior-king father entered the dialectic with Christianity, the warrior king won, and the hope of his becoming more Christian lost. Hamlet engages more earnestly in the dialectics, but in the most sloppy way: The specter of his father suffering in purgatory makes him fearful of his own tendencies to sin, so he treats Ophelia and her beauty as things that would only tempt him toward damnation. Not the most Christian thing to do. He assumes it's Claudius behind the arras, and perhaps heaven and hell have sanctioned his revenge; but no, it's Polonius, who he kills by accident. Sloppy, not Christian. He later assumes that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern know the contents of the letter from the king, so he changes the letter to order his friends' deaths instead of his own. Also sloppy work on this point. He says he will "answer" later for the death of Polonius, but to Horatio he claims, like a king with right of conquest, that the deaths of his friends don't touch his conscience. This is not very Christian at all.

Yet he feels Providence has saved him at sea with the help of pirates, and in the graveyard, he receives a gift of remembrance of the affection that the court jester Yorick once showed him. He feels God has been merciful to him, so he becomes more aware of his mistakes, and prepares to be more merciful and apologetic toward Laertes. The warrior-Christian dialectic his father failed at so abysmally is now something the prince is slightly more adept at.

THE CHRISTIAN-WARRIOR DIALECTIC PHRASED AS A JOKE

"St. Francis and Genghis Khan walk into a bar....

Who wins?"

Well, as the bible and a certain Flannery O'Connor title say, "The Violent Bear It Away."

In the larger biblical context, the phrase comes from Matthew 11:12; in Shakespeare's time, the 1599 bible put it this way:

And from the time of John Baptist hitherto, the kingdom of God suffereth violence, and the violent take it by force.

John the Baptist and many other prophets were killed; the violent take things by force, they "bear it away."

Or perhaps as Flannery O'Connor's Catholic Douay-Rheims translation put it: "And from the days of John the Baptist until now, the kingdom of heaven suffereth violence, and the violent bear it away."

NO JOKE

Even asking the question of who wins between St. Francis and Genghis Khan implies we are thinking more like Genghis Khan than like St. Francis. The monk Francis was famous for taking seriously the gospel command to love one's enemies, even meeting with the Sultan of Egypt during the 5th Crusade.

The warrior may think he wins (according to warrior standards) if he kills, or fights and wins against St. Francis.Then it's not a dialectic, but just violence.

Francis wins if he is more kind and patient, more willing to listen, to open his mind and heart to the other, more willing to act as a servant. Francis wins if, like Jesus, he speaks the truth, acts in love, and perhaps in some situations, is willing even to die, or in others, willing to be changed.

So the Christian who engages in an open-minded, open-hearted dialectic is perhaps acting most Christian (paradoxically) if she or he is willing to listen and learn and be changed by the other. The same Christianity that counsels love of enemies and welcome to strangers bids the Christian to enter into fruitful dialectics, not only with friends and family, but perhaps especially with strangers and enemies. This is not required of the warrior (although, for example, Sun Tsu's The Art of War would counsel the warrior to learn from enemies, or at least metaphorically to allow one's enemies to be one's teachers).

SOMETHING ROTTEN IN CHRISTIANITY AFTER CONSTANTINE

Many have noted that the Christians of the early church may have acted more in harmony with the gospel than it seems Christianity did after the conversion of Constantine and the militarization of Christianity in kingdoms, in a "holy" Christian empire set to conquer new lands and claim them for Christ, the "prince of peace."

Too often, it seems that in the warrior-Christian dialectic, the warrior won.

We can see this in part in the Roman Catholic Church's "Doctrine of Discovery," made up of papal bulls that encouraged Christian explorers and armies to seek out and subdue aboriginal people in distant lands. As noted in a 2015 article in The Conversation, one of these bulls encouraged Christians

"...to invade, search out, capture, vanquish, and subdue all Saracens and pagans…the kingdoms, dukedoms, principalities, dominions, possessions, and all movable and immovable goods…held and possessed by them."

Christianity in the USA is still plagued in this way, with Christian warriors and evangelists seeking to win "victories for Jesus" against strangers whose culture and religion are different. Too many of them assume that spreading American military empire and capitalism is the same as spreading Christianity.

This is evident in complaints and tensions in the US armed forces, where military leaders pressure soldiers to attend evangelical meetings, a problem that surfaced during the 2003 war in Iraq, and still persists, as demonstrated in violation of rules reported in August of 2018. The warriors are winning, and subduing Christianity to act in service of war and military empire.

THE WAY THE HAMMER SHAPES THE HAND

The danger of any dialectic is that something essential may be lost if one side gives in too much to the other. Instead of Christians recognizing some things about warrior culture that must be rejected as incompatible, more often, Christianity has been assimilated and subjugated to serve the goals of warrior culture. The Christian who takes up weapons of war will be changed by those weapons, "the way the hammer shapes the hand," in the words of songwriter Jackson Browne. His song, "Casino Nation," explores this relationship:

In a weapons producing nation under Jesus

In the fabled crucible of the free world

Camera crews search for clues amid the detritus

And entertainment shapes the land

The way the hammer shapes the hand

Gleaming faces in the checkout counter at the Church of Fame

The lucky winners cheer Casino Nation

All those not on TV

Only have themselves to blame

And don't quite seem to understand

The way the hammer shapes the hand

Out beyond the ethernet the spectrum spreads

DC to daylight, the cowboy mogul rides

Never worry where the gold for all this glory's gonna come from

Get along dogies, it's coming out of your hides

The intentional cultivation of a criminal class

The future lit by brightly burning bridges

Justice fully clothed to hide the heart of glass

That shatters in a thousand Ruby Ridges

And everywhere the good prepare for perpetual war

And let their weapons shape the plan

The way the hammer shapes the hand

Lyrics by Jackson Browne, 2002

Hamlet's way of thinking about his position as disappointed prince and as son of a murdered king is necessarily influenced by his idolizing of a warrior-king father whose ghost (he believes) has asked him to avenge his murder. The hammer of royal power and warrior status has already shaped the hand of the prince. But thoughts of his eternal fate and Christian teachings tug him in other directions.

EISENHOWER'S WARNING

President Dwight Eisenhower, formerly a general who had served in Europe in World War II, was a fiscal conservative. It annoyed him to watch congress approve many unnecessary programs for military spending that would create jobs in many states and thereby assist incumbent representatives and senators in being reelected. He knew that, if the US was constantly approving the production of weapons and supplies for war, and if there was so much profit to be made from war, we would probably become a nation that would be more inclined to seek military conflicts. The hammer of more military weapons would shape the hand of a nation whose founders warned against entanglements in foreign wars, but which increasingly had ignored the advice of its founders.

In his "Chance for Peace" speech after the death of Stalin in 1953, drawing upon biblical phrases and Christian imagery, Eisenhower is famous for having said,

Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed.

This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children. The cost of one modern heavy bomber is this: a modern brick school in more than 30 cities. It is two electric power plants, each serving a town of 60,000 population. It is two fine, fully equipped hospitals. It is some fifty miles of concrete pavement. We pay for a single fighter with a half-million bushels of wheat. We pay for a single destroyer with new homes that could have housed more than 8,000 people. . . . This is not a way of life at all, in any true sense. Under the cloud of threatening war, it is humanity hanging from a cross of iron.

Eisenhower viewed the death of Stalin as an opportunity to reach arms agreements, end the cold war, and redirect monies that had been used for military spending toward meeting humanitarian needs. But this was not to be.

As a younger man, Eisenhower had been present on the capital mall when the "Bonus Army" gathered there during the depression years, a gathering of veterans who had been promised bonus pay after service in World War I, "The Great War" that had been said would end all wars. Marine Major General Smedley Butler had been a supporter of the veterans' demands and spoke to them on the mall. Butler had written a book, War is a Racket, which claimed that many US military engagements around the world were not to advance good will and democracy, but to advance the profits of large business interests. Eisenhower may have been influenced a bit by Butler's ideas later as he shaped his farewell speech, warning of the "military-industrial complex" (a phrase that had originally been, "military-industrial-congressional complex").

Eisenhower's warnings went largely unheeded. John Kennedy sought to end involvement in Vietnam and to enter into a variety of nuclear treaties, including the banning of above-ground nuclear tests. His generals wanted to fight and win a war against the Soviet Union, But Kennedy was assassinated, some believe, for his plans to pull out of Vietnam and for being perceived as too weak with the Soviets. As Jackson Browne notes, "In a weapons-producing nation under Jesus," the hammer of weapons had become too powerful in shaping the hand.

POLONIUS & REP. TED YOHO, SUGARING O'ER DEVILS WITH DEVOTION'S IMAGE

In Shakespeare's Hamlet, Polonius gives Ophelia a prayer book and wants her to read it when she first sees the prince in act 3, scene 1. Polonius says,

We are oft to blame in this,

'Tis too much prov'd, that with devotion's visage

And pious action we do sugar o'er

The Devil himself.

This is another example of failed dialectics, when the image of religiosity is used to serve dishonest purposes. We saw something like this just this past week, when Rep. Ted Yoho (R-Florida) accosted Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez on the capital steps, calling her "disgusting" and a"fucking bitch" for suggesting some people steal because they are hungry. Later, in a non-apology, Yoho said "I rise to apologize for the abrupt manner of the conversation I had with my colleague from New York...The offensive name calling words attributed to me by the press were never spoken to my colleagues." In other words, he apologizes only for abruptness, not for calling AOC names that a reporter overheard. Yoho added, " “I cannot apologize for my passion, or for loving my God, my family, and my country.”

So Yoho sugars o'er the devil by denying he used the offensive language, and claiming his abruptness was motivated in part by his love of God.

Again, in the warrior-Christian dialectic, the warrior clearly has won in Yoho, and the ostensibly Christian language is subordinated to serve the goals of the warrior.

Yoho resigned from the board of a Christian organization, perhaps under pressure after his uncivil remarks. Author David Talbot (The Devil's Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the Rise of America's Secret Government) had an appropriate and humorous brief comment about Yoho's resignation:

But in a larger context, Yoho inadvertently highlighted AOC in the role of the Christian victim, taking the side of the poor and imprisoned, and being made to suffer in public for it. Rebecca Traister does a good job exploring how the exchange between Yoho and AOC fits into a larger context of "gendered power imbalance in political, public, and personal life." (Many thanks to Emanuela Zanchi for sharing a link to Traister's essay.)

WARRIOR-CHRISTIAN DIALECTICS AND INTELLECTUAL COLONIZATION

Perhaps we see another example of the warrior-conqueror winning out in the warrior-Christian dialectic in instances of intellectual colonization. We often hear teachers claim that they learn more from their students in the long run than students learn from them. At best, this may be evidence of teachers who are open to two-way dialectics with their students, allowing the students to provide new insights. But at worst, some teachers may say this, but still practice a form of intellectual colonization, where the teacher has all the answers and the students must be subjugated by the teacher's superior ideas. In a larger sense, citizens of many nations are considering ways that the effects of colonial rule have persisted even after colonial rulers have left; persisted through the effects of the colonizer's language and ideas. Many resources explore and debate this. For just a few examples:

- ResearchGate.net has an interesting PDF of a paper on the effects of a Commonwealth adult education program, asking whether it actually liberates, or perhaps is an example of intellectual colonialism.

- In India, some have noted that the English language has intellectual-colonizing effects and propose the importance of Indian scientists and academics writing in their first languages, while others claim that this "would be disasterous."

- In a 2007 essay, "Imperialist Democracy, Intellectual Colonialism," by Hassan Tahsin, the author points out a variety of important concerns.

If a colonizer claims to want to save a culture and a people by introducing western values, the hidden motive is often access to resources and profit. This is more the warrior-conqueror at work, and if we are to call it Christian, it's the version of Christianity that has already been made rotten by its dialectics with warrior-conqueror empires.

MORE RESOURCES

Much has been written about classical allusions in Shakespeare, including Hamlet; Professor Philip Allingham of Lakehead University in Canada has a good web page that serves as an introduction to classical allusions in the play. For those new to my blog, for more on the presence of biblical allusions, see Naseeb Shaheen's book, Biblical References in Shakespeare's Plays (2011), and for plot echoes, consider viewing my list of "greatest hits" (best and most popular blog posts about biblical plot echoes in Hamlet).

For those interested in more from Paul A. Cantor, he has a series of three lectures on YouTube that you may find of interest:

- Hamlet (1 of 3)

[In this video, Cantor mentions "Renaissance man" and what an "early modern man" would think of as a Renaissance man; he pauses because he knows it's sexist, but then he prefers it anyway for how it sounds. Cantor is an older scholar, so this is the language he uses; it's a limitation, but there are still many gems in the videos.

- He also mentions around 6:00 the year 1453 and the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman turks as a turning point, where fleeing scholars brought to the west ancient texts they had heard of but not known, leading to a kind of golden age.

- He speaks of the Aristotelia virtues contrasted with the Christian virtues, and how these surface in interesting combinations in visual art and in poetry such as Spencer's Fairie Queen.

- Later (15:41), he notes that, typically, the virtues (Aristotelian) that make you succeed in war will not help you succeed in peace.- Around 23:00 he mentions the stark contrast between Laertes, who upon hearing of his father's death will not let Christianity or damnation stand in the way of his revenge, in stark contrast with Hamlet. So as a foil, Laertes is not merely more a man of action than Hamlet as many note, but he is also much less concerned with his eternal fate, as also later shown by his remark about cutting Hamlet's throat in the church.

- Around 26:00, he speaks of Horatio as a different sort of foil, a stoic (but perhaps a stoic would not allow himself to be swayed, changed in a fruitful dialectic?)

- 31:20, comments on sending Rosencrantz & Guildenstern to their deaths, "not shriving time allowed" (as the ghost claimed to have none allowed for him) - and Hamlet acting like a man of action instead of a melancholic.

- 32:45, Hamlet as a political and ambitious man.]

- Hamlet (2 of 3)

- Hamlet (3 of 3)

For those interested in more of my work on dialectics between characters in Hamlet, I discuss this by another name: Gift dynamics, or "labors of gratitude," where characters say and/or do things that become like gifts, which influence other characters in a larger matrix of dialectics. You can read more of my thoughts on these dialectics in a series of posts: I presented a paper on this just this year (a Zoom meeting version of our Shakespeare Association of America seminar), described in the following post (SAA Seminar: “Shakespeare & the Mind: Cognition, Emotion, Affect").

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Disclaimer: If and when I quote or paraphrase bible passages in many of my blog posts, I do not intend to promote any religion over any other, nor am I attempting to promote religious belief in general; only to point out how the Bible may have influenced Shakespeare, his plays, and his age.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading!

My current project is a book tentatively titled Hamlet’s Bible, about biblical allusions and plot echoes in Hamlet.

Below is a link to a list of some of my top posts (“greatest hits”), including a description of my book project (last item on the list):

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2019/12/top-20-hamlet-bible-posts.html

I post every week, so please visit as often as you like and consider subscribing.

Yet another incredibly insightful entry, Dr. Fried.

ReplyDeleteOphelia, she's 'neath the window for her I feel so afraid/

On her twenty-second birthday she already is an old maid/

To her, death is quite romantic she wears an iron vest/

Her profession's her religion, her sin is her lifelessness/

And though her eyes are fixed upon Noah's great rainbow/

She spends her time peeking into Desolation Row

Thanks, Michael, and for the Bob Dylan lyric as well!

DeleteMaybe "Desolation Row" also describes the spiritual state of those who don't engage in the dialectics, taking the best from various sources, and being changed for the better - like Claudius?

Ophelia is still a mystery to me, but I think I see her less like Dylan and more like her brother in the graveyard, speaking to the churlish priest:

Ophelia will be a ministering angel, while the priest will lie howling....