Hamlet & The Spanish Tragedy as a Conversation

If you ask actors about the influences, differences, and similarities between Thomas Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy and Shakespeare's Hamlet, some may respond that one could never prove the nit-picking speculations of academics, and that both are revenge plays with plenty of material for actors to bring to life, and for audiences to be drawn in. Shakespeare was an entertainer, and he wanted to make a good living, so if he borrowed elements from Kyd, as long as the shows are a success with audiences and at the box office, everyone is happy.

[Images: The Spanish Tragedy via Wikipedia; Hamlet Q2, via Folger Shakespeare Library.]

Of course, in a way, they're right. Actors still bring very old plays to life for audiences who are moved, again and again, by something not only in the scripts, but in the actors and the audiences themselves. When things come together well in a live performance, why dig and speculate about historical questions that might never be answered?

And yet the questions scholars ask are motivated in part by the creative spark we feel from the plays, and the work of scholars to better understand the political, religious, cultural, artistic (and other - culinary! and more!) contexts for the plays, these questions are themselves often imaginative ones, questions that articulate imaginative speculations that are sometimes later supported by evidence and accepted as true.

Regarding just one of these contexts, these plays were obviously not written in a political vacuum. For The Spanish Tragedy: Elizabeth I's sister Mary I had been married to Philip II of Spain, and in spite of the controversies stemming from Henry VIII marrying the widow of his brother Arthur, he had hoped to marry Elizabeth before relations between England and Spain deteriorated, so this and other international developments certainly influenced the writing of Kyd's play.

For Hamlet, set in Denmark: Eventually James VI of Scotland married Anne of Denmark in 1589, and later became King of England in 1603, a historical fact that may certainly have influenced the development from perhaps the lost Ur-Hamlet to Shakespeare's three later-published versions.

In this sense, the plays are conversations, at least inasmuch as they respond to political and other historical developments. But did they also involve conversations between playwrights and plays?

Some may dismiss the possibility that The Spanish Tragedy and Shakespeare's Hamlet were also quite intentionally developed in conversation, complaining that playwrights merely crank out plays as distractions for the masses and a means for income. But in fact scholars for more than a century have noticed similarities and differences between the plays, and speculated about the two as a conversation.

I am no expert on Kyd, but am inclined to think Shakespeare was talking back to Kyd and to his popular play. Here are just four examples of the many scholars who have weighed in on the subject, one from 1906, and three since 2010:

In 1906, The Sewanee Review published "The 'Spanish Tragedy' and 'Hamlet'" by Henry Thew Stephenson, in which Stephenson argues that Hamlet improves upon similar elements in Kyd's play. Many other scholars have joined the fray, noting similarities and differences, and wrestling with their significance to both plays and their respective writers.

Brian Vickers wrote in 2012 about the possibility that Shakespeare had written lines added to a later edition of Kyd's play, as noted in an Oxford blog post by Douglas Bruster. Bruster in turn noticed how certain spelling patterns in additions to The Spanish Tragedy may have been caused by tendencies in Shakespeare's handwriting, as evidenced by "Hand D" in a manuscript of Sir Thomas More (as noted in the Wikipedia article on The Spanish Tragedy, in the section on authorship, accessed 7 Sept. 2020, and in the 2013 New York Times article it references).

This doesn't mean that Shakespeare wrote the entire play, The Spanish Tragedy," but that he may have written certain additions.

[Image: A page from a manuscript of Sir Thomas More via the Folger Shakespeare Library.]

Dramaturg Mary Ann Koory (for Marin Shakespeare Company) notes in her blog (#11, "Author Brand Name") regarding Professor Brian Vickers work on the possibility of Shakespeare's hand in the additions to Kyd's play.

Maley Holmes Thompson wrote a 2015 dissertation for the University of Texas at Austin related to these 320 lines added to Kyd's play, and suggests these lines are a middle step between The Spanish Tragedy and Hamlet.

Both plays present audiences with stories about apparently unbearable corruption in high places (Spain and Portugal, or Denmark respectively).

But in spite of a long list of similarities, the plays are very different in their development of their protagonists. (For those unfamiliar with the parallels, a good place to start, besides Stephenson's 1906 essay mentioned above, is Wikipedia's article on Hieronimo, in the sub-section comparing Hieronimo to Hamlet).

In The Spanish Tragedy, the protagonist, Hieronimo, is the father of Horatio, who is killed by Prince Balthazar, son of the Portuguese Viceroy, and Lorenzo, Duke of Castile, nephew to the Spanish King. Although Hieronimo is Knight Marshal of Spain and therefore an enforcer of law and justice, he is thwarted in his efforts to obtain justice for the murder of his son, in part because the murderers arrange to make the king believe Hieronimo's son Horatio is still alive. The Spanish Tragedy works its way toward a violent ending in which Hieronimo arranges for many deaths during a play-within-the-play, and has at times been viewed as demonstrating a pagan sense of revenge as justice, or of the Hebrew scripture adage, "An eye for an eye," rather than a Christian sense of leaving vengeance and justice to God.

The Spanish Tragedy contains relatively few biblical allusions compared to Shakespeare's Hamlet. And notably, Hamlet not only descends into madness that leads him to display cruelty to Ophelia, extreme revenge so as to play God in damning Claudius (the subject of last week's blog post), and bloody thoughts that lead him to mistake Polonius for Claudius behind the arras, and to send Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to their deaths.

But Hamlet also has a conversion after his descent into madness, violence, and sin: He has a Jonah-like change in mode of transportation mid-sea, changing to a pirate ship instead of the belly of a fish.

["Jonah and the Whale" by Pieter Lastman, 1621, Museum Kunstpalast, via Wikipedia; public domain.]

In spite of his having killed Polonius and sent two friends to their deaths, he experiences the mercy of Providence (God) through pirates, "thieves of mercy" (4.6). Having experienced the mercy of God, in spite of his killing and apparent sinfulness, Hamlet is transformed by the gift of this mercy, and later becomes more merciful to others, especially Laertes, with whom he exchanges forgiveness in the final scene, and Fortinbras, whose father was killed by Hamlet's father.

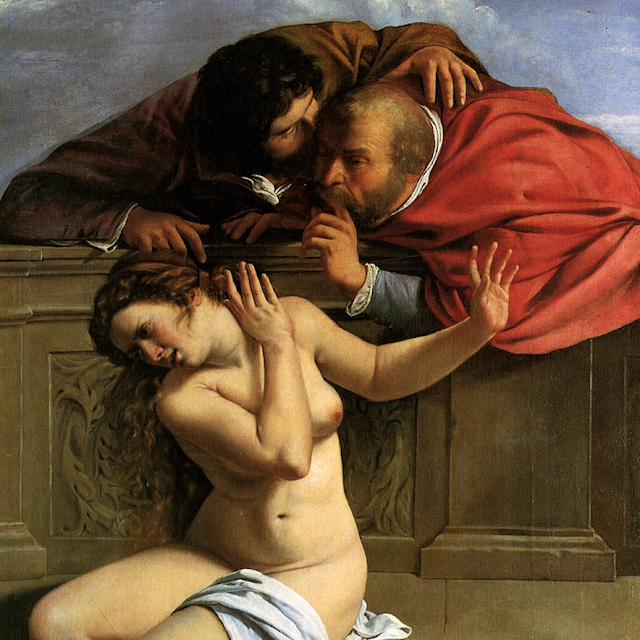

Frank Ardolino has pointed out in his book, Apocalypse and Armada, that the Hebrew scripture tale of Suzannah and the corrupt elders was popular in Elizabethan times and sometimes used to defend Elizabeth from her critics. Ardolino notes that there is an echo of the Suzannah tale in The Spanish Tragedy, when Bel-Imperia and Horatio are caught in the garden, not by two corrupt judges, but by Lorenzo and Prince Balthazar, when (in a departure from the scripture plot), the two men kill Horatio.

[Painting, 1610 Artemisia Gentileschi via Wikipedia; public domain.]

I have noted before that there is a similar echo of the Suzannah tale in the nunnery scene (3.1), when Ophelia agrees to help two corrupt elders, Claudius and her father Polonius, by spying on Hamlet, but again, the Shakespeare play, like its predecessor, departs from the details of the scripture plot, having Ophelia (who in this case is like Suzannah) as a willing collaborator with the corrupt elders, instead of firmly opposed to their plans.

Considering that the Suzannah tale was used to defend Elizabeth, the virgin queen, we might wonder if Kyd's play revises the tale to have the Suzannah-Elizabeth figure, Bel-Imperia, meeting Horatio for a sexual liason (many in Shakespeare's England wondered if Elizabeth was not so much the virgin queen).

And in the same way, we might wonder if Shakespeare revises the biblical plot to have the Suzannah-Elizabeth figure, Ophelia, collaborate with more powerful and corrupt men, including William Cecil (Polonius), in allowing and agreeing to an extensive and invasive program of spying on her own people.

Unlike The Spanish Tragedy, Hamlet also contains an echo of the Emmaus tale in the graveyard scene, as I have noted in previous blog posts: The biblical tale is about two disciples on the road to Emmaus, who meet a stranger they do not recognize at first as Jesus, but later do recognize him in the breaking of the bread.

[Image: "Supper in Emmaus" by Matthias Stom, 1601. Photograph taken at: Corps et Ombres : Le Caravagisme européen, Musée des Augustins, 23 July 2012–14 October 2012 , Caroline Léna Becker. Public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 100 years or fewer. Via Wikipedia.]

In the graveyard scene, Hamlet and Horatio, two Danes, are like the two disciples, on the road to Elsinore instead of Emmaus. The stranger is the gravedigger-clown, who was drinking buddies with Yorick, the king's jester, whose skull Hamlet finds; it turns out that Yorick, the gravedigger, and Hamlet are kindred spirits. This is an important moment of grace for Hamlet, and it seems to have no parallel in any redemption plot arc in The Spanish Tragedy.

Given the many similarities between the two plays, I do not believe that the striking differences between them are merely the random results of yet another Elizabethan entertainer, writing yet another tragedy to make a living. Rather, I believe it's Shakespeare's way of continuing his conversation with Kyd's work, perhaps begun in 320 lines he may have added to a revised later edition of Kyd's play. Just as Macbeth contains that touching scene between Lady Macduff and her son (4.2), like a moment of grace in a play about great evils, Shakespeare may have believed it important to take many elements from Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy and transform them in light of Christian themes that were familiar in Shakespeare's lifetime.

Where The Spanish Tragedy may be more pagan and vengeful, Hamlet is more Christian in its outlook, with a spiritual conversion toward mercy on the part of the prince.

Regarding those who are killed by the protagonist in the final scene of each play: If Hieronimo is an officer of justice in Spain, and if Prince Hamlet is perhaps the rightful king of Denmark, then how are such authority figures to act as ministers of justice? They cannot let all criminals go free, perhaps to do more evil, claiming that vengeance belongs to God alone. They have jobs to do in promoting the peace and protecting their people from crime and violence. If monarchs are considered (as many thought them) God's anointed, and officers of justice as commissioned by those monarchs, then when they arrange to punish or pardon suspected criminals, they are not pursuing private revenge, but justice; perhaps when they do their work well, the people assume God achieves proper vengeance through them.

The Spanish Tragedy presents corruption in high places but kills only Lorenzo, Prince Balthazar, and by suicide, Bel-Imperia; if the marriage of Balthazar and Bel-imperia had taken place, their children would have been heirs to the throne of Spain, so this effectively leaves the future of the Spanish throne in question. But Shakespeare goes a step further in Hamlet, having the Prince of Denmark kill the murderous and usurping king Claudius.

In their own ways, these were dangerous thoughts, to live in a time of English monarchy and to write and perform plays in which kings and/or their heirs were killed. Perhaps because Shakespeare situates his plot and redemption arc for Hamlet more in the context of a conversion to faith in a merciful Providence, he can afford to risk having a prince kill a king in his play and avoid being censored?

Why were they popular? Thinking about these two plays might lead us to wonder why revenge tragedies were so popular at the time. Consider, if one were to guess and only had two choices:

a) Perhaps revenge plays like Hamlet popular in their time because the people of England felt their own government was mostly free from corruption, so they never had fantasies of avenging injustices, but such plays were good escapist entertainment? Or . . .

b) Revenge tragedies were popular precisely because people of the time sometimes viewed their own government (or recent governments) as corrupt, and felt powerless to correct it?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Disclaimer: If and when I quote or paraphrase bible passages in many of my blog posts, I do not intend to promote any religion over any other, nor am I attempting to promote religious belief in general; only to point out how the Bible may have influenced Shakespeare, his plays, and his age.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading!

My current project is a book tentatively titled Hamlet’s Bible, about biblical allusions and plot echoes in Hamlet.

Below is a link to a list of some of my top posts (“greatest hits”), including a description of my book project (last item on the list):

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2019/12/top-20-hamlet-bible-posts.html

I post every week, so please visit as often as you like and consider subscribing.

[Images: The Spanish Tragedy via Wikipedia; Hamlet Q2, via Folger Shakespeare Library.]

Of course, in a way, they're right. Actors still bring very old plays to life for audiences who are moved, again and again, by something not only in the scripts, but in the actors and the audiences themselves. When things come together well in a live performance, why dig and speculate about historical questions that might never be answered?

And yet the questions scholars ask are motivated in part by the creative spark we feel from the plays, and the work of scholars to better understand the political, religious, cultural, artistic (and other - culinary! and more!) contexts for the plays, these questions are themselves often imaginative ones, questions that articulate imaginative speculations that are sometimes later supported by evidence and accepted as true.

Regarding just one of these contexts, these plays were obviously not written in a political vacuum. For The Spanish Tragedy: Elizabeth I's sister Mary I had been married to Philip II of Spain, and in spite of the controversies stemming from Henry VIII marrying the widow of his brother Arthur, he had hoped to marry Elizabeth before relations between England and Spain deteriorated, so this and other international developments certainly influenced the writing of Kyd's play.

For Hamlet, set in Denmark: Eventually James VI of Scotland married Anne of Denmark in 1589, and later became King of England in 1603, a historical fact that may certainly have influenced the development from perhaps the lost Ur-Hamlet to Shakespeare's three later-published versions.

In this sense, the plays are conversations, at least inasmuch as they respond to political and other historical developments. But did they also involve conversations between playwrights and plays?

Some may dismiss the possibility that The Spanish Tragedy and Shakespeare's Hamlet were also quite intentionally developed in conversation, complaining that playwrights merely crank out plays as distractions for the masses and a means for income. But in fact scholars for more than a century have noticed similarities and differences between the plays, and speculated about the two as a conversation.

I am no expert on Kyd, but am inclined to think Shakespeare was talking back to Kyd and to his popular play. Here are just four examples of the many scholars who have weighed in on the subject, one from 1906, and three since 2010:

In 1906, The Sewanee Review published "The 'Spanish Tragedy' and 'Hamlet'" by Henry Thew Stephenson, in which Stephenson argues that Hamlet improves upon similar elements in Kyd's play. Many other scholars have joined the fray, noting similarities and differences, and wrestling with their significance to both plays and their respective writers.

Brian Vickers wrote in 2012 about the possibility that Shakespeare had written lines added to a later edition of Kyd's play, as noted in an Oxford blog post by Douglas Bruster. Bruster in turn noticed how certain spelling patterns in additions to The Spanish Tragedy may have been caused by tendencies in Shakespeare's handwriting, as evidenced by "Hand D" in a manuscript of Sir Thomas More (as noted in the Wikipedia article on The Spanish Tragedy, in the section on authorship, accessed 7 Sept. 2020, and in the 2013 New York Times article it references).

This doesn't mean that Shakespeare wrote the entire play, The Spanish Tragedy," but that he may have written certain additions.

[Image: A page from a manuscript of Sir Thomas More via the Folger Shakespeare Library.]

Dramaturg Mary Ann Koory (for Marin Shakespeare Company) notes in her blog (#11, "Author Brand Name") regarding Professor Brian Vickers work on the possibility of Shakespeare's hand in the additions to Kyd's play.

Maley Holmes Thompson wrote a 2015 dissertation for the University of Texas at Austin related to these 320 lines added to Kyd's play, and suggests these lines are a middle step between The Spanish Tragedy and Hamlet.

Both plays present audiences with stories about apparently unbearable corruption in high places (Spain and Portugal, or Denmark respectively).

But in spite of a long list of similarities, the plays are very different in their development of their protagonists. (For those unfamiliar with the parallels, a good place to start, besides Stephenson's 1906 essay mentioned above, is Wikipedia's article on Hieronimo, in the sub-section comparing Hieronimo to Hamlet).

In The Spanish Tragedy, the protagonist, Hieronimo, is the father of Horatio, who is killed by Prince Balthazar, son of the Portuguese Viceroy, and Lorenzo, Duke of Castile, nephew to the Spanish King. Although Hieronimo is Knight Marshal of Spain and therefore an enforcer of law and justice, he is thwarted in his efforts to obtain justice for the murder of his son, in part because the murderers arrange to make the king believe Hieronimo's son Horatio is still alive. The Spanish Tragedy works its way toward a violent ending in which Hieronimo arranges for many deaths during a play-within-the-play, and has at times been viewed as demonstrating a pagan sense of revenge as justice, or of the Hebrew scripture adage, "An eye for an eye," rather than a Christian sense of leaving vengeance and justice to God.

The Spanish Tragedy contains relatively few biblical allusions compared to Shakespeare's Hamlet. And notably, Hamlet not only descends into madness that leads him to display cruelty to Ophelia, extreme revenge so as to play God in damning Claudius (the subject of last week's blog post), and bloody thoughts that lead him to mistake Polonius for Claudius behind the arras, and to send Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to their deaths.

But Hamlet also has a conversion after his descent into madness, violence, and sin: He has a Jonah-like change in mode of transportation mid-sea, changing to a pirate ship instead of the belly of a fish.

["Jonah and the Whale" by Pieter Lastman, 1621, Museum Kunstpalast, via Wikipedia; public domain.]

In spite of his having killed Polonius and sent two friends to their deaths, he experiences the mercy of Providence (God) through pirates, "thieves of mercy" (4.6). Having experienced the mercy of God, in spite of his killing and apparent sinfulness, Hamlet is transformed by the gift of this mercy, and later becomes more merciful to others, especially Laertes, with whom he exchanges forgiveness in the final scene, and Fortinbras, whose father was killed by Hamlet's father.

Frank Ardolino has pointed out in his book, Apocalypse and Armada, that the Hebrew scripture tale of Suzannah and the corrupt elders was popular in Elizabethan times and sometimes used to defend Elizabeth from her critics. Ardolino notes that there is an echo of the Suzannah tale in The Spanish Tragedy, when Bel-Imperia and Horatio are caught in the garden, not by two corrupt judges, but by Lorenzo and Prince Balthazar, when (in a departure from the scripture plot), the two men kill Horatio.

[Painting, 1610 Artemisia Gentileschi via Wikipedia; public domain.]

I have noted before that there is a similar echo of the Suzannah tale in the nunnery scene (3.1), when Ophelia agrees to help two corrupt elders, Claudius and her father Polonius, by spying on Hamlet, but again, the Shakespeare play, like its predecessor, departs from the details of the scripture plot, having Ophelia (who in this case is like Suzannah) as a willing collaborator with the corrupt elders, instead of firmly opposed to their plans.

Considering that the Suzannah tale was used to defend Elizabeth, the virgin queen, we might wonder if Kyd's play revises the tale to have the Suzannah-Elizabeth figure, Bel-Imperia, meeting Horatio for a sexual liason (many in Shakespeare's England wondered if Elizabeth was not so much the virgin queen).

And in the same way, we might wonder if Shakespeare revises the biblical plot to have the Suzannah-Elizabeth figure, Ophelia, collaborate with more powerful and corrupt men, including William Cecil (Polonius), in allowing and agreeing to an extensive and invasive program of spying on her own people.

Unlike The Spanish Tragedy, Hamlet also contains an echo of the Emmaus tale in the graveyard scene, as I have noted in previous blog posts: The biblical tale is about two disciples on the road to Emmaus, who meet a stranger they do not recognize at first as Jesus, but later do recognize him in the breaking of the bread.

[Image: "Supper in Emmaus" by Matthias Stom, 1601. Photograph taken at: Corps et Ombres : Le Caravagisme européen, Musée des Augustins, 23 July 2012–14 October 2012 , Caroline Léna Becker. Public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 100 years or fewer. Via Wikipedia.]

In the graveyard scene, Hamlet and Horatio, two Danes, are like the two disciples, on the road to Elsinore instead of Emmaus. The stranger is the gravedigger-clown, who was drinking buddies with Yorick, the king's jester, whose skull Hamlet finds; it turns out that Yorick, the gravedigger, and Hamlet are kindred spirits. This is an important moment of grace for Hamlet, and it seems to have no parallel in any redemption plot arc in The Spanish Tragedy.

Given the many similarities between the two plays, I do not believe that the striking differences between them are merely the random results of yet another Elizabethan entertainer, writing yet another tragedy to make a living. Rather, I believe it's Shakespeare's way of continuing his conversation with Kyd's work, perhaps begun in 320 lines he may have added to a revised later edition of Kyd's play. Just as Macbeth contains that touching scene between Lady Macduff and her son (4.2), like a moment of grace in a play about great evils, Shakespeare may have believed it important to take many elements from Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy and transform them in light of Christian themes that were familiar in Shakespeare's lifetime.

Where The Spanish Tragedy may be more pagan and vengeful, Hamlet is more Christian in its outlook, with a spiritual conversion toward mercy on the part of the prince.

Regarding those who are killed by the protagonist in the final scene of each play: If Hieronimo is an officer of justice in Spain, and if Prince Hamlet is perhaps the rightful king of Denmark, then how are such authority figures to act as ministers of justice? They cannot let all criminals go free, perhaps to do more evil, claiming that vengeance belongs to God alone. They have jobs to do in promoting the peace and protecting their people from crime and violence. If monarchs are considered (as many thought them) God's anointed, and officers of justice as commissioned by those monarchs, then when they arrange to punish or pardon suspected criminals, they are not pursuing private revenge, but justice; perhaps when they do their work well, the people assume God achieves proper vengeance through them.

The Spanish Tragedy presents corruption in high places but kills only Lorenzo, Prince Balthazar, and by suicide, Bel-Imperia; if the marriage of Balthazar and Bel-imperia had taken place, their children would have been heirs to the throne of Spain, so this effectively leaves the future of the Spanish throne in question. But Shakespeare goes a step further in Hamlet, having the Prince of Denmark kill the murderous and usurping king Claudius.

In their own ways, these were dangerous thoughts, to live in a time of English monarchy and to write and perform plays in which kings and/or their heirs were killed. Perhaps because Shakespeare situates his plot and redemption arc for Hamlet more in the context of a conversion to faith in a merciful Providence, he can afford to risk having a prince kill a king in his play and avoid being censored?

Why were they popular? Thinking about these two plays might lead us to wonder why revenge tragedies were so popular at the time. Consider, if one were to guess and only had two choices:

a) Perhaps revenge plays like Hamlet popular in their time because the people of England felt their own government was mostly free from corruption, so they never had fantasies of avenging injustices, but such plays were good escapist entertainment? Or . . .

b) Revenge tragedies were popular precisely because people of the time sometimes viewed their own government (or recent governments) as corrupt, and felt powerless to correct it?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Disclaimer: If and when I quote or paraphrase bible passages in many of my blog posts, I do not intend to promote any religion over any other, nor am I attempting to promote religious belief in general; only to point out how the Bible may have influenced Shakespeare, his plays, and his age.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading!

My current project is a book tentatively titled Hamlet’s Bible, about biblical allusions and plot echoes in Hamlet.

Below is a link to a list of some of my top posts (“greatest hits”), including a description of my book project (last item on the list):

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2019/12/top-20-hamlet-bible-posts.html

I post every week, so please visit as often as you like and consider subscribing.

Paul,

ReplyDeleteI have used this material -- https://www.jstor.org/stable/456489?seq=3#metadata_info_tab_contents -- previously. It's 20 pages but a somewhat quick read.

Thanks, Michael! I think that in my research for that post, I came across a reference to some of the same stuff, perhaps that very article, quoted by another source! Must be onto something!

Delete