Jephthah-Figures in Hamlet: Ambitious, Desperate, Traumatized Outsiders?

When Hamlet compares Polonius to Jephthah in 2.2 (1451-66), it is commonly thought that this merely refers to an ambitious Jephthah making reckless (or unholy) vows that will later result in the death of his daughter.

But this week I will explore the idea of Jephthah as a marginalized person, marginalized for being the son of a prostitute and therefore driven out, treated as "other" and outsider, likely traumatized by that marginalization. For that reason, Jephthah may have been desperate for acceptance by those who had excluded him.

This may explain why he makes his rash vow that he will sacrifice to God whatever comes first across his threshold if he returns victorious from battle, and his daughter becomes the victim.

These aspects of the Biblical Jephthah tale may also offer a lens through which to consider Polonius, object of Hamlet's Jephthah metaphor, and the king's key counselor who some scholars have associated with Poland, where the previous king "in an angry parle, / ...smote the sledded Polacks on the ice" (1.1.78-9).

These and other aspects of the Jephthah tale may also offer us a way of viewing Fortinbras as a Jephthah figure.

WHAT THIS LINE OF THOUGHT DOES NOT REQUIRE

Exploring this angle does not require Prince Hamlet, the character, to be fully aware of all aspects of his comparison. Hamlet's use of the metaphor may have been more narrow than that of the playwright. It is common for a playwright or fiction writer to use character dialog to convey themes and metaphors whose import is much greater than the characters themselves may realize. That seems to be the case with Hamlet's Jephthah metaphor for Polonius.

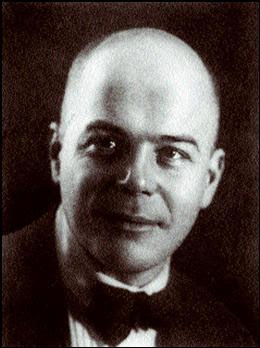

Also, the playwright need not to have been fully conscious of the many possible implications of the Jephthah allusion: The D.H. Lawrence poem, "Song of a Man Who Has Come Through" begins, "Not I, not I, but the wind that blows through me!" Writers sometimes make inspired choices that resonate with more meaning than they realize at first.

[D.H. Lawrence (1885-1930), passport photo (date & photographer unknown; Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University; public domain).]

ALLUSIONS & METAPHORS ARE NOT A CIPHERS

When Hamlet alludes to the Jephthah tale as a metaphor for Polonius, we might be tempted to treat it as a cipher, or in other words, to decode the reference as having only one meaning:

- Jephthah makes a reckless and ambitious vow that harms his daughter; Polonius is like that.

But the Jephthah tale is richer than these narrow plot elements, so we should resist closing down possibilities (or what some would call "reifying" or thing-ifying first insights). We may be missing out on other correspondences.

Hamlet's use of the Jephthah metaphor is somewhat jarring and sudden in its context. This may not be as much the case as with the love poetry Hamlet includes in his letters to Ophelia, which, one could easily argue, seems filled with clichés. It could be argued that the metaphors (and even scientific allusion - Copernican doubt of the Ptolemaic geocentric model) in Hamlet's love poetry are more expected.

But because the Jephthah reference is jarring, out of the blue, it may feel to audiences as if it fits what Russian Formalist Viktor Shklovsky (1893-1984) described as "defamiliarization," or "making strange": Especially when an allusion or metaphor is unexpected, but to some extent with all allusions as analogies, we are invited to consider something in a fresh way by means of the allusion.

[Viktor Borisovich Shklovsky (1893–1984). Image via Wikicommons, public domain.]

Hamlet doesn't explain why he offers the Jephthah metaphor, whether it relates also to himself having made a rash vow to the ghost, or merely to Polonius placing his ambitions for his job above his daughter's welfare, or other possible reasons. The play is so often ambiguous, many claim it raises more questions than it answers (and that may be one of its main purposes, to keep us from plucking the heart of mystery via frequent ambiguity). He merely quotes from a song or ballad that speaks of Jephthah and his daughter, as if comparing Polonius to Jephthah, or perhaps, more ambiguously, pretending to see if Polonius knows the lines.

Unfortunately, as we become more familiar with our own insights and our favorites of other scholars, we may be tempted to treat the Jephthah reference, either as a cipher pointing to a single (perhaps we think most-important) meaning, or to a set (or reified) matrix of possible meanings of which we are aware.

But once our favorite interpretations of the metaphor become familiar (and perhaps reified), then the original defamiliarizing effect of the allusion may no longer be doing its work in us.

So this blog post is an invitation to relax what might be our familiar scholarly assumptions, and revisit the defamiliarizing effects of the original comparison.

JEPHTHAH, MARGINALIZED SON OF A PROSTITUTE, SUDDENLY NECESSARY

The story in Judges 11-12 involves Jephthah, the son of a prostitute. His father was Gilead, who also had children by a wife, but as these other children grew, they drove Jephthah out. This is analogous to the biblical tale of Abraham and Sarah: At first they were unable to have children, so Sarah gave her slave Hagar to Abraham to bear a son for them. Hagar bore Ishmael, but Hagar and Ishmael were later driven away out of jealousy after Sarah bore Isaac.

Jephthah is driven away, but he is good at fighting (perhaps in part because he frequently had to defend himself, first against his siblings, and then after they rejected him, against strangers in the world). He goes to the land of Tob, where he becomes a leader of a band of "scoundrels," which probably further allows him to hone his fighting skills. (If Jephthah as a leader of scoundrels sounds a bit like Fortinbras gathering a bunch of ruffians to make war on Denmark, perhaps it should.)

When the Israelites of Gilead are attacked by Ammonites, the leaders of Israel realize they are in need a good fighter to help them, so they send for Jephthah. The once-rejected half-sibling whose mother was a harlot suddenly becomes necessary for their survival. Tables are turned.

If it occurred today, we'd say that, to entice him, they promised Jephthah an extremely nice compensation package with a golden parachute. In fact, they tell him that if he defeats the Ammonites, they will make him their leader. It is an offer the once-marginalized Jephthah is unwilling to refuse.

LIKE YOUNG FORTINBRAS,

JEPHTHAH FAILS NOT TO PESTER WITH MESSAGE, BUT PREVAILS

Young Fortinbras, quite surprisingly, follows many aspects of the Jephthah plot:

1. Fortinbras is cut off from his father's inheritance, like Jephthah kicked out of his father Gilead's home by his half-siblings.

2. He gathers up a band of idle men and ruffians or thieves to attack Denmark, like Jephthah, who took up with a similar group of men after being kicked out of Gilead's home.

3. Fortinbras attempts diplomacy to settle his land dispute with Norway, pestering Claudius with letters, like Jephthah, attempting diplomacy with the Ammonites.

4. In the end, Fortinbras gets the throne of Denmark, like Jephthah, who becomes leader of the Israelites of Gilead.

5. While Jephthah sacrifices his own daughter after his victory, Fortinbras seems quite willing to sacrifice many soldiers, the sons of others, in a war for a piece of land that one of his soldiers considers worthless. These sacrifices come before Fortinbras obtains the throne of Denmark in part as a result of the gift of Hamlet's dying voice, so the chronology is flipped a bit, but the elements are still present.

These parallels are surprising in part because (to my knowledge) Fortinbras is never named as a Jephthah figure by Shakespeare scholars.

In particular, Jephthah engages in attempts at diplomacy with the Ammonites, sending messages to the Ammonite king, first asking why they choose to attack, and later after they respond, Jephthah sends them another message, explaining why Israel believes they have a right to possess the lands the Ammonites wish to claim.

This sounds very much like Fortinbras, pestering Denmark with message, asking for the return of lands taken by Denmark when King Hamlet had killed his father, Old Fortinbras in single combat:

Claudius: He hath not failed to pester us with message

Importing the surrender of those lands

Lost by his father, with all bonds of law,

To our most valiant brother. (1.2.200-203)

Horatio makes a point of it in 1.1 (99-112) that, at least Denmark's version of the story is that King Hamlet won the land fair and square, and if Old Fortinbras had been victorious, Denmark would have forfeited their land to Norway. In Denmark's view, it is all legitimate by law and heraldry (1.1.104).

This may remind some readers of what French economist Claude-Frédéric Bastiat described as legal plunder:

"Lorsque la Spoliation est devenue le moyen d’existence d’une agglomération d’hommes unis entre eux par le lien social, ils se font bientôt une loi qui la sanctionne, une morale qui la glorifie."

("When plunder becomes a way of life for a group of men in a society, over the course of time they create for themselves a legal system that authorizes it and a moral code that glorifies it.")

- Economic sophisms, 2nd series (1848), ch. 1 Physiology of plunder

But this leaves open the possibility that Young Fortinbras and Norway may see things in a very different way, just as Jephthah and the Ammonites saw things very differently.

In the Kenneth Branagh film version of Hamlet, Claudius tears up the letter from Fortinbras as he says, "So much for him" (1.2.203).

In the Jephthah tale, the Ammonites are similarly dismissive of Jephthah's account of Israel's history and claims to the land. But after making his rash and destructive vow, Jephthah prevails over the Ammonites.

And as we know, in the end, although Fortinbras is the traumatized outsider, with the help of Hamlet's dying voice, he becomes king of Denmark.

This is a lovely correlation between the two stories: Polonius is not the only Jephthah figure in the play for how his unwise choices endanger his daughter, and neither is Hamlet for accepting the Ghost's command that he swear to avenge. Fortinbras is also a Jepthah figure, for being marginalized by Denmark after his father's death, even as Jephthah was by his half-siblings; for being a fighter like Jephthah and gathering around himself a band of scoundrels or ruffians; for attempting diplomacy before violence, as Jephthah did; and for prevailing in the end.

MARGINALIZED (AND TRAUMATIZED?) JEPHTHAH

A key detail in the Jephthah story is that he is marginalized, driven out, because he is the son of a prostitute, not like one of the other children who claim that only they, and not Jephthah, are due an inheritance from their father.

Consider: Perhaps in patriarchal cultures, especially where women are treated as possessions, where faithfulness and exclusivity in marriage is valued as the ideal, one will always find prostitution as a kind of pressure valve, where men who stray from the cultural ideal seek an outlet for their lust. In such cultures, there are bound to be women who are found unacceptable for marriage, for whatever reason, and some of these may turn to prostitution for survival, or may be exploited as such by men. Perhaps Gilead, Jephthah's father, frequented the same prostitute often enough that both he and the prostitute knew he was likely the father? The story doesn't say. It simply says Jephthah was the son of Gilead and a prostitute, and it implies that this makes his status lower and shameful in comparison to the children of Gilead and his wife, so Jephthah is driven out.

It feels at this point in the story as if there is something inherently unfair: Perhaps Jephthah's mother did not choose to be a prostitute but did it out of economic necessity; Jephthah did not choose to be the son of a prostitute. The fact that he is, resulted from choices his father Gilead made, not his own choices. Bible scholars may debate the chronology of the various scripture passages that lay down rules of hospitality, and which admonish Israel to "welcome the stranger, for you were once strangers." Jephthah is a half-sibling to the other children of Gilead, sharing the same father, and yet he is driven out, a kind of violence that echoes the violence of Cain, son of Adam and Eve, against his brother Abel, and Cain, like Hagar and Ishmael, being driven out.

This part of the story also therefore seems thematically related to Claudius murdering his brother, king Hamlet: Claudius wants the throne of Denmark entirely to himself. The half-siblings of Jephthah want their father's inheritance entirely to themselves.

BEING TERRITORIAL, BEING TRAUMATIZED

We might say that Jephthah's half-siblings were being too territorial, and in that way, seemed to violate at least the spirit if not the letter of certain rules of hospitality that eventually required welcoming the stranger or outsider. Jephthah is an outsider in their view because he is the son of a prostitute.

Notes on the inclination to be territorial:

This year we became dog owners, and we have noticed how territorial our dog can be when she hears other dogs bark or sees neighbors walking their dogs. She is descended from Anatolian sheepdogs and perhaps a bit from Great Pyranees, so the fact that she is territorial and suspicious of other dogs (and also cats) may be due in part to trauma suffered by her ancestors, guarding livestock. If it was the job of a long line of your ancestors to guard flocks against attacking wolves, wild dogs, and other predators, your first impulse upon smelling or seeing strange animals might be to tense up, growl, be ready to fight, and to feel your blood pressure quickly rise.

[Anatolian Shepherd Dog. Public domain image.]

For humans whose ancestors were frequently at war or subjected to tribal raids, the inclination might be similar: To distrust outsiders and be ready to defend against and fight them, drive them out.

Some studies since 2013 have shown that there may be inter-generational effects of trauma, passed on to descendents, not only in mice, but also in descendents of Union prisoners during the Civil war (also here), victims of trauma in orphanages and their descendents, descendents of Vietnam War veterans who suffered PTSD, and Holocaust survivors. Some of these studies observe that this effect may be more pronounced in male descendents.

There have been critics (or claims of "debunkers") of aspects of these studies, as might be expected, but as more studies have been published in recent years, it seems likely that trauma may have inter-generational effects that are passed on biologically ("nature"), and not just socially ("nurture") in families.

This may explain at least some of the nationalism, racism, and xenophobia we witness among Trump supporters in the US, Brexit supporters in the UK, in parts of the European Union, and other countries of the world. And therefore, the more veterans a nation has suffering from PTSD, the more likely their male descendents may be "triggered" to fear and dislike outsiders, and to support new wars, perpetuating the cycles of trauma.

THE NECESSITY OF UNDERDOGS AND OUTSIDERS

Traditions and rules for hospitality toward strangers, such as those found in the Judeo-Christian scriptures, then, would seem to counter some of the worst inclinations many humans and other animals have toward outsiders.

But just as being territorial may be a kind of survival instinct borne of trauma, it might also be said that welcoming the stranger, or elevating the underdog, can serve other survival patterns, and may be shown in stories of how a stranger or underdog became a savior-figure for the people. Sometimes being too territorial runs counter to the needs of the group for survival, and new insights, methods, and "new blood" (or new DNA?) from outsiders and strangers are exactly what the group may need in certain circumstances.

And in a very practical sense, a nation that has a bad reputation of being inhospitable to vulnerable strangers and guests may one day be attacked by the nations from which those strangers have come. Being territorial and suspicious of strangers may be a first instinct, especially for those who have been traumatized by strangers in war, or descended from those traumatized. In that context, that first instinct may seem like a survival instinct in its own way. But welcoming the stranger may in fact be a wiser survival instinct in the long run for those who would rather make allies than provoke wars.

The bible is full of tales in which the outsider or underdog prevails: Isaac's sons, Esau and Jacob, were non-identical twins, and (except for a quirky and probably apocryphal detail of Jacob sticking a foot out and then pulling it back in before birth) Esau was born first, so he would have been due the birthright and the favored inheritance. But instead, for a variety of reasons, the birthright goes to Jacob, the underdog, who seems more fit for the job of remembering and passing on the family heritage.

The Book of Ruth is about a foreigner demonstrating greater faith than many of the local neighbors, and therefore showing that inclusion and open-mindedness may at least sometimes be far more important than exclusivity.

In the story of Judith, when Holofernes brought an army against Israel, a war-widow named Judith dressed up to make herself appear most beautiful and visited the enemy camp, spending three days as the guest of Holofernes, seemingly as a gift in the hope that Holofernes and his army would show Israel mercy; but she helped get him drunk and then cut off his head, doing what Israel's army was unable to do and achieving victory, proving that sometimes help and salvation comes from the unexpected place.

[Judith Beheading Holofernes - by Artemisia Gentileschi. 1611-1612. Public domain via Wikipedia.]

Of the many sons of Jesse, David was the young afterthought, not even present when the prophet came to anoint a new king from among them (David was out tending the sheep and missed the big meeting). But the prophet asks David's father: Haven't you any other sons? David, the overlooked, the underdog, becomes the chosen one, and slays the giant. Again, help and salvation sometimes come from the unexpected place.

[David and Goliath, from Henry VIII Psalter: Henry as David, and the pope who would not give him the annulment he sought as Goliath. Image via British Library.]

When Jerusalem was occupied by Rome, the empire's leaders decided they would pick the high priest of the Jews as a kind of Roman puppet. Then along came Jesus (or "Yahshua," perhaps closer to what he would have been called in his own land), son of a carpenter, the last person most Jews may have expected to become a teacher and leader of people. The synoptic gospels (Mt 21:42; Mk 12:10–11; Lk 20:17) quote Psalm 118 to describe Jesus similarly as "the stone the builders rejected" that "becomes the cornerstone" even as David had been rejected by Saul but "obtained the kingdom" (1599 Geneva translation notes).

So Jephthah is in this Biblical-literary tradition of marginalized, rejected, or overlooked outsiders or underdogs who prevail.

THE ABUSED BECOMES AN ABUSER

But in the case of Jephthah, we might especially note how the trauma of that marginalization may not only have played a role in his becoming a fighter, but may also have played a role in his desperate vow to God that he would sacrifice whatever first crossed his threshold, if only God would help him be victorious.

They say that victims of abuse sometimes become abusers themselves, and in the case of Jephthah, it would seem that he is passing on to his own daughter, in sacrificing her, something of the trauma and violence of the abuse he suffered at the hands of his half-siblings. Freud's idea of repetition compulsion is that sometimes people feel compelled to repeat some aspect of their trauma, perhaps especially if it's a memory they'd rather forget. (In Marjorie Garber's book, Shakespeare After All, in her Hamlet chapter, she mentions Freud's idea of repetition compulsion in association with the prince (496), but it may apply even more clearly to Jephthah).

In Shakespeare's Hamlet, not only is the Danish prince presented as a traumatized and excluded person (who lost his father but is kept from inheriting the throne); Fortinbras is similarly portrayed, and eventually Ophelia and Laertes fit the pattern as well.

And yet it is not these but Polonius to whom Hamlet assigns the analogy of Jephthah.

[Above, images from ShakespearesGlobe.com for 2019 event.]

POLONIUS AS OUTSIDER AND TRAUMATIZED POLE?

In the First Quarto (Q1), the character who is later named Polonius was called Corambis. Because Q1 had been mostly lost to history and collective memory until rediscovered in 1823, some assumed it was a bad attempt to transcribe from memory the supposedly superior Q2. Eventually, others speculated that Q1 may have been a shorter, touring copy for when Shakespeare's acting company was unable to play in London (or across the Thames) due to theater closures during the plague. Still others believe that Q1 reflects an earlier draft, but that Shakespeare and his company later added material (as the Q2 title page claims) and made refinements (resulting eventually in Q2 and the First Folio, or F1).

So at least one possibility is that the name "Polonius" is a refinement, not merely to avoid trouble for satirizing the family motto of William Cecil, but also to draw a connection between the counselor as having ancestral roots in Poland, and Polish enemies of the dead King: Horatio in 1.1 describes the dead King Hamlet as having fought "the sledded Polacks on the ice" during "an angry parle," what footnotes sometimes describe as implying a truce negotiation (parle/parley) gone wrong.

If Shakespeare wanted to connect Polonius with Poland and King Hamlet's enemy, what might that imply for Shakespeare the writer, in his own time, and what might it imply for Polonius, the character?

For Shakespeare:

Shakespeare's England was officially Protestant, although historians have noted that, for decades after Henry VIII broke from Rome, and later after the death of (Catholic) Mary I, the majority of the population, especially those far from London, may still have considered themselves more Roman Catholic in religious allegiance than Protestant.

Poland and Lithuania had joined, after Lithuania had been strong-armed by Poland, eventually resulting in the Union of Lublin of 1569; he Lithuanian church that had been more allied with the Eastern Orthodox church agreed to come under Roman Catholic jurisdiction. The presence of Jesuit priests in Poland was expanding in Shakespeare's lifetime.

Jesuits and other Roman Catholic priests in England had to operate in secret, and some were suspected of conspiring against Elizabeth. With the help of bad weather at sea, England had defeated the Armada of Catholic Spain. So for Shakespeare to choose (Catholic) Poland as the enemy of King Hamlet to smite on the ice, makes sense: The sympathies of London Protestant theatergoers might be inclined toward the brave Danish king, making war with those demonized Catholic Poles.

While many of the English converted to Protestantism or were at least outwardly observant, many others there remained at least secretly Catholic, harboring priests so that they could continue to observe the mass and other Roman Catholic sacraments. Some were split in their allegiances - "double-hearted" as the name "Corambis" implies - and wanted to remain faithful Catholics while still trying very hard to demonstrate to Elizabeth that they were also loyal subjects, faithful to the crown.

These Catholics - openly Catholic, but perhaps trying very hard to demonstrate English crown loyalties - were perhaps very much like Claudius describes himself in 3.3, using a gospel allusion: "like a man to double business bound" (see Mt 6:24, "No man can serve two masters: for either he shall hate the one, and love the other, or else he shall lean to the one, and despise the other"). They were also perhaps like Gertrude in her closet who tells Hamlet he has "cleft [her] heart in twain" (3.4.2539); he responds that she should "throw away the worser part of it, / And live the purer with the other half" (2541-2), alluding to the gospel verses about how, if a person's eye or hand offends them, they should "pluck it out" or "cut it off" because it's better to enter heaven without them than to have the whole body burn in the flames of hell (Mk 9:43-49; Mt 5:29-30).

Besides a possible satire of William Cecil, Polonius the ambitious boot-licker may have seemed to Shakespeare - and to some in his audiences - like some of the Catholic nobles who bent over backwards to remain in the good graces of the crown. This would seem consistent with Poland having been an enemy to Denmark, and the Danish monarchy having a key advisor who is Polish, and a sycophant.

But if at least in part Shakespeare is offering a satire of William Cecil in the character of Corambis/Polonius, we might observe: Cecil traced his ancestry to Walterstone and the Welsh Marches on the eastern border that Wales shares with England, about twice as far from London as Stratford-Upon-Avon. His ancestor David Cecil moved to Stamford, Lincolnshire, about as far from Walterstone as London.

Why the move? Ambition? Famine (and its associated trauma)? Family or local strife (trauma)? Did Cecil in some part of his consciousness view himself as an outsider motivated in part, like Jephthah, by fear for his survival that may have expressed itself as extreme ambition?

As many have observed, the play hints at possibilities, but in the end, its ambiguities raise more questions than they answer.

For Polonius:

But what does this imply for Polonius to be the key and senior counselor to the Danish monarchy, if he or his ancestors were Polish? What occurred to make a man whose nation had been enemies of Denmark become welcomed as chief advisor?

Some possibilities:

- His ancestors immigrated to Denmark, for any number of reasons, before the armed conflict with Denmark referred to by Horatio in 1.1.

- He personally immigrated to Denmark, perhaps with family members, during peacetime, and to take advantage of new opportunities.

- He was a refugee of war.

- He was expelled from Poland for some reason, deported (rejected, marginalized, as Jephthah was by his half-siblings).

- He was an advisor to the Polish throne who became a prisoner of war and changed allegiances.

- He left his homeland due to dissatisfaction there (any number of reasons).

- He was a traitor to his homeland of Poland, perhaps a spy and informant for Denmark, betraying Poland in favor of ambition for greater opportunities offered by the Danish king.

Even if he or his ancestors immigrated to Denmark during a time of peace, most of these possibilities could be wrapped in fear or prompted in part by some kind of trauma, at least relating to King Hamlet's violence against the "the sledded Polacks on the ice." While others from his homeland were dying, he may have had fears for his own survival and that of his family.

When Claudius in 1.2 speaks of his gratitude toward Polonius, which extends toward the son Laertes, it is clear that the relationship is at least tinged with fear, as Laertes speaks of Claudius in that scene as "dread lord," and as Polonius later tells Claudius and Gertrude they can take his head from his shoulders ("this from this," 2.2) if he is wrong in his hunch that Hamlet is mad due to disappointed love for Ophelia.

In other words, he is telling his boss and monarch, who has the power to order people to be beheaded, that he can have him beheaded if he is wrong. This seems a very unwise gamble, and in fact the madness in Hamlet may be far more due to the news of his father's murder and the ghost's command to revenge, than due to the loss of Ophelia.

This offer by Polonius, for the monarchy to take his head from his shoulders if wrong, is like a Jephthah vow:

Jephthah: I will sacrifice whatever crosses my threshold if you bring me victory, O God.

Polonius: You can take my head if I'm wrong about the cause of Hamlet's madness, dread lord.

In Jephthah's case, because we learn the back-story of the family history and Jephthah's marginalization as the son of a prostitute, it seems there may be a connection between his early trauma of being driven out and excluded, and his desperate vow to God. The vow may be motivated by a hunger to be included, with a vengeance: to come out on top, where he was previously made to feel that he was at the bottom of, or simply excluded from, the family and larger social hierarchy.

In the case of Polonius, we are not told his family's history, but Prince Hamlet's Jephthah allusion offers us an analogy for Polonius that hints at these possibilities.

Addendum, 1 February 2021: I realized as I thought back on this blog post that the Jephthah tale is thematically related to the Lazarus/Rich Man allusions in the play: Like the beggar Lazarus who is marginalized, kept out of the rich man's house, Jephthah is marginalized by his family. In the end, the beggar Lazarus is in heaven; in the end, Jephthah becomes the ruler of the people of Gilead.

There are differences in the story, to be sure: Lazarus does not sacrifice a daughter. But the similarities are important as well.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hamlet quotes: All quotes from Hamlet are taken from the Modern (spelling), Editor's Version at InternetShakespeare via the University of Victoria in Canada. They are often first identified by way of the advanced search feature at OpenSourceShakespeare.org.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

RECENT BLOG POSTS ABOUT POLONIUS & JEPHTHAH:

October 6, 2020: Power-Broker Polonius, Ungenerous Jephthah

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2020/10/powerbroker-polonius-ungenerous-jephthah.html

November 24, 2020: Is Hamlet's Jephthah remark in part about Cecil & the Bond of Association?

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2020/11/hamlet-jephthah-cecil-bond-assn.html

December 1, 2020: Polonius, Apuleius, Golden Ass, Arras, & Hidden Lovers

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2020/12/polonius-apuleius-golden-ass-arras.html

December 8, 2020: William Cecil: Top Among 12 Polonius Satire/inspiration Candidates

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2020/12/william-cecil-top-among-12-polonius.html

December 15, 2020: Jephthah-Figures in Hamlet: Ambitious, Desperate, Traumatized Outsiders?

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2020/12/jephthah-polonius-cecil-ambitious.html

December 22, 2020: Jephthah, Cecil, & Three Instruments in Hamlet

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2020/12/jephthah-cecil-three-instruments-in.html

December 29, 2020: J.G. McManaway: Ophelia & Jephtha's Daughter

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2020/12/jg-mcmanaway-ophelia-jephthas-daughter.html

January 5, 2021: What Art Might Remind Us About Jephthah, Polonius, & Ophelia

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2021/01/what-art-might-remind-us-about-jephthah.html

January 12, 2021: Jephthah & Polonius: What’s prostitution got to do with it?

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2021/01/jephthah-polonius-whats-prostitution.html

January 19, 2021: What's Jephthah to Hecuba, or She to Him?

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2021/01/whats-jephthah-to-hecuba-or-she-to-him.html

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Disclaimer: If and when I quote or paraphrase bible passages in many of my blog posts, I do not intend to promote any religion over any other, nor am I attempting to promote religious belief in general; only to point out how the Bible may have influenced Shakespeare, his plays, and his age.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading!

My current project is a book tentatively titled Hamlet’s Bible, about biblical allusions and plot echoes in Hamlet.

Below is a link to a list of some of my top posts (“greatest hits”), including a description of my book project (last item on the list):

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2019/12/top-20-hamlet-bible-posts.html

I post every week, so please visit as often as you like and consider subscribing.

Comments

Post a Comment