If the Ghost was like the Rich Man, who was his Lazarus? (Part 2)

It is easy to be confused when the ghost in Shakespeare's Hamlet says that the poison his brother Claudius poured in his ear made King Hamlet's skin all "lazar-like." There are many possible sources of confusion:

LAZAR-LIKE? LAZAR-HOUSE? LEPROSY?

- First, many modern readers and potential audience members of the play don't know what leprosy is, or that a "lazar-house" was a hospital for lepers. This was common knowledge in Shakespeare's time, but is much less familiar to modern readers and playgoers.

SORRY TO DISAPPOINT SCHOLARS OF EARLY MODERN SCIENCE

We might imagine at this point that there may be a scientist or botanist

who is also a Shakespeare fan, and who wonders if there may have been

some poison known in Shakespeare's time that had the ability to curdle

the blood and change the victim's skin so quickly to be entirely covered

in crust. I hate to disappoint those scientists whose inclination might

be to start at the literal level and ask such questions. But to move in

that direction would be to take this passage far too literally, when

it's meant to be an allusion to the gospel story.

LAZAR-LIKE, AS IN LAZARUS OF GOSPEL PARABLE FAME?

- Second, many people today don't know the story of the beggar Lazarus and the rich man in Luke 16:19-31, whereas in Shakespeare's England where church attendance was mandatory by law, most people were familiar with the tale. So if a reader or playgoer is unfamiliar with the gospel parable, one might be tempted to check the footnotes and find that "lazar-like" relates to the condition of his skin, and leave it at that.

WHY DOES THE GHOST RETURN, WHEN LAZARUS COULD NOT?

- Third, in Luke 16, the rich man in hell asks Abraham if Lazarus can be sent back from the dead to warn his brothers, but is told he cannot: They have the law and the prophets, and if they will not believe those, they would not be convinced by someone returned from the dead. If Lazarus cannot return from the dead to warn the living, why has the ghost been allowed to return from the dead to warn Prince Hamlet?

This might be something like the Protestant thinking that would have denied the existence of purgatory and ghosts, and therefore concluded that any apparition claiming to be a spirit of a person returned from the dead is probably a demon in disguise. So by using the phrase, "lazar-like," the ghost is pointing to a chapter in the Bible that might be used to deny the very possibility of ghosts returning to warn the living. If we tug at this thread too hard, the whole fabric of the ghost's story might unravel.

TOO MANY FOUL CRIMES AND CRIMINALS?

- Fourth (and most important for the purposes of today's blog post), even if we know the gospel story, we might think at first that King Hamlet, a murder victim, was like the good though poor beggar in the gospel tale, and someone else (like his usurper-brother, Claudius) was the greedy rich man who was neglecting or oppressing him.

Readers and playgoers may experience some cognitive dissonance on this point, because the ghost describes his brother Claudius as being like the snake in the garden of Eden who brings about the downfall of Adam and Eve. Claudius in that sense is clearly the villain, while the ghost describes himself as the victim who, because his brother killed him before he had confessed his sins and received the last rites, he is to spend a time suffering while his sins are "purged away" to prepare him for heaven. Many readers and critics have assumed that the ghost was mostly a good king, and Hamlet certainly idolizes him, comparing him to Titans and gods of mythology.

But in fact, closer examination reveals the possibility that King Hamlet may have been more like the rich man, and his lazar-like skin may point to the fact that he is being punished for a lack of generosity in life. The play is ambiguous on this point, just as it is on the question of whether the ghost is from purgatory or a demon in hell, taking the shape of Hamlet's father to damn him.

King Hamlet is dead, and the ghost's detail of the lazar-like skin forces us to consider that he is being punished for his sins by becoming, after death, more like the beggar Lazarus was in life. The ghost says,

I am thy father's spirit,

Doomed for a certain term to walk the night,

And for the day confined to fast in fires,

Till the foul crimes done in my days of nature

Are burnt and purged away. (1.5.694-8)

He is "doomed," being punished for "foul crimes" he committed while in life, and this punishment will continue until his sins are purged.

Because so many critics ignore the detail of the lazar-like skin as a possible allusion to the gospel parable, and also ignore the ghost's reference to his "foul crimes," we should consider other possibilities.

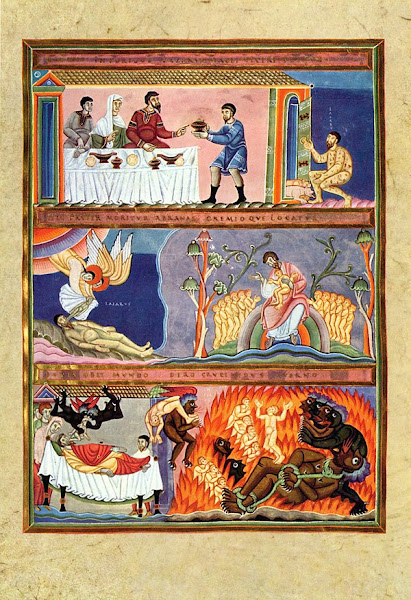

[Lazarus and Dives, illumination from the Codex Aureus of Echternach, circa 1035-1040. Public domain. Image via Wikipedia.

Top panel: Lazarus at the rich man's door.

Middle panel: Lazarus' soul is carried to Paradise by two angels; Lazarus in Abraham's bosom

Bottom panel: Dives' soul is carried off by Satan to Hell; Dives is tortured in Hades]

A REVERSAL OF FORTUNE TALE

The gospel tale is a story of a reversal of fortunes: Before their deaths, the rich man enjoys luxury and food inside his home or estate. The poor beggar Lazarus is hungry at his gate and suffers with sores that cover his skin and are licked by dogs. He is excluded, ignored by the ungenerouos rich man.

After they die, Lazarus is in heaven with Abraham, while the rich man suffers in hell. Their places have changed: Now the beggar Lazarus is rich with his heavenly reward, and the rich man is excluded, in pain, thirsty, begging for a drink, but it's too late for him because of how ungenerous he was in life.

By reading old criticism or commentary on Shakespeare's Hamlet, one finds that many readers and viewers of the play over the centuries have tended to downplay the "foul crimes" (1.5.697) that the king claims he committed, which resulted in his time in purgatory instead of being admitted to heaven. They tend to want to believe that Hamlet's father was a good king, in part perhaps because Hamlet remembers him that way - or idolizes him instead of remembering him. The prince has nothing bad to say of his father, and his praise is all hyperbole driven by analogies of Greek gods.

If we read the play that way, we might prefer to think that King Hamlet is in purgatory only on a technicality, for not having received the Catholic sacraments before his death. Some may believe that what the ghost describes as his "foul crimes" must have in fact been relatively minor sins which, in the Catholic view, have to be purged away before he can be admitted to heaven.

In this case, the ghost would be like the beggar Lazarus, and his brother Claudius would be like the unfeeling rich man. The ghost will only spend a short time in purgatory, like a car-wash for sins, before he will go to be in heaven like Lazarus. Claudius will eventually die and end up in hell, as many would assume because Claudius is absolutely unrepentant to the end, unrepentant at prayer, unwilling to expose himself as a murderer by crying out to prevent Gertrude from drinking the poison cup. Soon enough King Hamlet will be in heaven, Claudius in hell, and all will be right with the world.

Or not?

This is a tempting interpretation, but a very flawed one.

A PROBLEM WITH GOD AND PURGATORY

One problem with this reading is that it depends on a religious worldview that requires a God who is a nit-picker for perfection, a bean-counter, more harsh judge than merciful heavenly Father: Even if King Hamlet had been a mostly good king, he will not be admitted to heaven on a technicality. He didn't receive the last sacraments before he died.

In such a worldview, few souls would escape spending at least a little time in purgatory for at least the minor sins they had committed, and which had been unrepented or unconfessed. If one believes that God really works this way, then the old Catholic system of having priests and monks and convents of nuns pray for the souls of the departed (usually in exchange for some charitable donation) would seem quite helpful.

But did Shakespeare and his mostly-Christian audience really believe in such a God?

There were many in England who still believed and secretly practiced the Roman Catholic faith. But except for a brief return to Roman Catholicism under Mary I, English authorities (Henry VIII, his son Edward, and his daughter Elizabeth) had rejected this religious view in their separation from Rome. Henry VIII had made himself as monarch the head of England's church. All bishops and priests had to comply with a mostly-Protestant worldview. They viewed the old system of saying masses for the dead as a corrupt one that preyed on people's fears to take their money, and on this basis, they had closed monasteries and convents and seized their land.

If in fact people need to have their souls purged before entering heaven, why can't an omnipotent God accomplish this purging in an instant at death? Does this God delay the purging of souls by way of limited suffering, only to draw out the process so that convents and monasteries can attract more money from families over a longer period of time? (It is a silly idea. And I say this as a person who was baptized Catholic soon after birth. We do well to remember that religions are social constructs: God doesn't make religions; people do.)

THE PROBLEM OF KING HAMLET'S "FOUL CRIMES" AND THE CHANGE IN HIS SKIN

Another problem with assuming the ghost is mostly good and a Lazarus figure, while the only villain is only Claudius, is that it requires us to downplay what the ghost himself describes as "foul crimes." It also requires that we downplay the detail of the change in his skin after the poisoning.

What were King Hamlet's "foul crimes"? In the case of the rich man in Luke 16, his foul crimes were the way he neglected the beggar Lazarus.

What if King Hamlet's "lazar-like" skin points primarily to a reversal of fortunes? The man who had been a rich king (but a sinner, guilty of "foul crimes") must suffer and be delayed entry into heaven, while the brother who had been excluded ascends the throne quickly after murder?

If the detail of the lazar-like skin points to a reversal of fortunes, then we might consider how the ghost of the dead king is being forced to switch positions and know what it's like to be like Lazarus, the beggar.

The rich man becomes a beggar only after he dies and goes to hell. The ghost also becomes a beggar through his death by poison. He is being punished for a time for his foul crimes, begging for release from his punishment. He begs for admittance to heaven, but he was a serious sinner. And he begs for Hamlet to avenge his murder.

So if the ghost was like the rich man, who was his Lazarus? Claudius is an obvious but strange candidate because he is also the murderer and usurper, which creates cognitive dissonance. But there are other candidates as well.

CANDIDATES FOR NEGLECTED BEGGARS IN THE LIFE OF KING HAMLET

If the ghost is being punished for having been ungenerous like the rich man was toward Lazarus, then who are the main candidates for Lazarus-figures in his life?

1. The poor of his kingdom

- If the play gave any evidence that the dead king had been ungenerous with the poor, then we might take the Lazarus-skin reference literally, but there's no such evidence in the texts. We might assume that, like many kings, he enjoyed a luxurious lifestyle while some in his kingdom experienced poverty, hunger, and disease; perhaps that is a given?

But without clear evidence in the text, we might also look elsewhere for other Lazarus figures.

2. Old Fortinbras

- Some scholars, especially since the 20th century, have pondered the "foul crimes" of the dead king and wondered if it had anything to do with his killing of Old Fortinbras. The way the Danes tell the tale, it seems to have been a sort of gamble, settling a land dispute in single combat between King Hamlet and Old Fortinbras. In the first scene of the play, Horatio says,

...our last King,

Whose image even but now appeared to us,

Was as you know by Fortinbras of Norway,

Thereto pricked on by a most emulate pride,

Dared to the combat (1.1.97-101)

We're not told clearly if only one or both were "pricked on" by "emulate pride," or if it began as a land dispute in which perhaps Fortinbras had a valid claim. But we're told that in the Danish view, there was a pact sealed before the fight that the loser of the fight would forfeit land to the winner. The two would gamble with their lives in the hope of winning the other's land.

Some scholars dismiss the idea that one of King Hamlet's foul crimes was his killing of Old Fortinbras, merely because Horatio says that the Danish version of the story claims it was all fair and square according to law and heraldry.

But Christianity believed that pride was the worst of the deadly sins, so it's certainly possible that at least one of King Hamlet's foul crimes was being pricked on to a fight over land with Old Fortinbras. And regardless of law and heraldry, the Bible tale of the murder of Abel by his brother Cain was sometimes seen as an analogy even for the killing that occurs in war, when distant brothers in the human family kill one another.

The mere fact that there was a sealed pact before the fight took place between King Hamlet and Old Fortinbras does not, by itself, make it right for them to have tried to kill the other in a gamble over land. The commandment familiar to all Christians in Shakespeare's time still said, "Thou shalt not kill." Dressing up pride and ambition in law and heraldry doesn't justify the foul crime of killing. It might simply make the attempts at justification appear more convincing or deceptive.

3. Prince Hamlet

- I have mentioned in an earlier blog post the fact that Prince Hamlet is the character who is most often described as "poor" or "begging" by others or himself. He names more specific memories of the affection of Yorick than he does of the father he idolizes. We might assume from these details not only that, as others have said, Yorick was an emotional surrogate-father-figure, but also that King Hamlet may have been emotionally absent from the prince's life. According to the gravedigger, the king was killing Old Fortinbras on the day Prince Hamlet was born. Maybe he was too busy fighting and being king to play an intimate role in his son's life, leaving his son like a beggar at the gate; instead of having leg-sores that were licked by dogs, Prince Hamlet's emotional needs were tended to by the royal fool, Yorick.

Would this be enough of a sin for the ghost (if he is in fact the king's ghost) to call it a "foul crime"? Many generations of mostly-male Shakespeare scholars might not think so.

But Shakespeare had a son who died during the time he was off in London, trying to make a name for himself as a poet and playwright. Perhaps Shakespeare felt he had neglected his son Hamnet in favor of his ambitions, and then after his death, it was too late. Maybe he felt that neglect of his son was a kind of "foul crime" of misplaced priorities? The 2018 film, All is True, written by Ben Elton, directed by Kenneth Branagh, explores this possibility, among other things.

4. Gertrude and Claudius

In the same way that Hamlet may have been starved for affection from a father-figure, Gertrude may also have lacked attention from her husband. In that sense, Gertrude may have been a Lazarus-beggar figure in King Hamlet's life.

Claudius may have felt neglected, his talents unused in his brother's kingdom, leaving him hungry for ways to be of use. And if his love relationship with Gertrude had a history that preceded her marriage to his brother, Claudius and Gertrude may have felt that her marriage to King Hamlet had been an impediment perhaps to their stronger and earlier love.

There was a historical precedent for a queen like Gertrude who had a previous love, married a king out of duty, and then married quickly after the death of the king. Shakespeare and others of his time would have known the story: The last wife of Henry VIII, Catherine Parr, had been in love with Thomas Seymour before Henry proposed. So Catherine married Henry dutifully, but within four months after Henry's death, Catherine secretly married Seymour, which eventually caused a scandal when the news was public. It was considered an "over-hasty marriage" like that of Gertrude to Claudius.

If the character of Gertrude and her hasty remarriage was inspired in part by Catherine Parr, we might wonder if the fictional Gertrude and Claudius had been in love before she had married King Hamlet. We know that Hamlet is a play about the end of a royal house, written at the end of the house of Tudor, so if it contained characters inspired in part by historical figures, including Tudor kings and queens, this should not surprise.

But there is no evidence in the text of the play that Gertrude and Claudius were in love before Gertrude married King Hamlet, so while such speculation might inform some actors and productions, it is not in the text. Actors often imagine back-stories not implied in the text in order to understand what motivates their character, but this can vary a great deal from one set of actors to another.

5. Claudius as dark parody of Lazarus

It is possible that Claudius is a dark parody of Lazarus - a murderous and envious Lazarus who changes places with the rich man, his brother, who had been guilty of "foul crimes"? This is a strong possibility, as the play contains a number of other seemingly dark parodies of scripture tales:

- In the first scene, some aspects resemble Jerusalem after the crucifixion, but before the resurrection, so the ghost seems to echo Jesus. But the ghost doesn't follow the rest of the gospel script for Jesus, and in fact seems far more evil than the risen Christ who, upon his appearances, bids his disciples not to fear. So Shakespeare seems to discard this allusion and its analogy as quickly as he took it up.

- Later in the same scene, with the ghost fading at the crowing of the cock, he seems to echo Peter after he denies Christ three times.

No longer a Christ-victim, the ghost would seem to be a Christ-denier. Yet he never fits the rest of the gospel script for Peter. So again, we have a brief allusion that offers its limited light and is then discarded.

- The ghost in 1.5 seems like a Moses-figure, giving the tablets of the law to Hamlet, or as Jesus in a dark parody of the transfiguration. But unlike Moses, who delivers the commandments - including not to kill - the ghost's command is for his son to avenge his murder. Unlike Jesus, who preaches forgiveness and love of enemies, the ghost preaches vengeance. If the ghost is at all like Moses on the mountain, or Jesus at the transfiguration, he seems a dark parody.

- Later in the play, Claudius trying to pray in 3.3 resembles aspects of Jesus praying before the passion, but this, too, seems a dark parody, as Jesus prayed, "thy will be done," whereas Claudius cannot bring himself to do the will of God and repent of his sins and what he gained by them.

For this reason, we might view the Lazar-like skin of King Hamlet after the poisoning as pointing both to his own foul crimes, but also to the reversal of fortune, with Claudius taking his throne, and King Hamlet becoming a ghost who begs for release from purgatory.

This is not quite the same as the tale of Lazarus and the rich man: Something in the analogy is definitely out-of-joint, like a dark parody, because Claudius the murderer and usurper is still alive and on the throne, and because King Hamlet had committed those unexplained "foul crimes" that landed him in purgatory. King Hamlet is clearly no beggar Lazarus before his death by poison, but neither is he merely like the rich man with a reputation for living in luxury and neglecting the beggars at his gate. He is merely in purgatory and not in hell, so if we take the ghost at his word (an option), he won't be in purgatory forever.

If Claudius is like the beggar Lazarus for wanting to use his talents and win Gertrude, his love, once he murders his brother, he is no longer a Lazarus-figure but a usurper.

The parable analogy, like Denmark, is therefore out-of joint. But no analogy is perfect, and Shakespeare gives us this detail of the lazar-like skin of the king (or ghost) to call to mind the analogy of the parable, without fitting that analogy perfectly. Like many other aspects of the play, we're left with yet another point of ambiguity.

On the one hand, we might wish things were more simple. On the other hand, the foul crimes and lazar-like skin mentioned by the ghost force readers and audience members to ponder: Who is good? Who is evil? Who is the criminal? What is out-of-joint here?

The world of our experience can easily be at least as morally ambiguous as that of the play. I live in the United States, a nation described by 1964 Nobel Peace Prize winner Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., as "the greatest purveyor of violence in the world" - a nation with more than 700 military bases on foreign soil around the world, including more than 200 military golf courses, with a military budget greater than its major allies and enemies combined.

Citizens of the United States enjoy access to inexpensive goods because capitalism exploits the cheapest labor, and then transports goods long distances, at great cost to the planet and its oceans, so that corporations can maximize their profits, and so that the rich can get richer. People around the globe who would dare to challenge practices of US corporations and the hegemony of the US petrodollar face a very strong adversary.

If I am so lucky as to live in a safe neighborhood and to enjoy many creature comforts - a warm house in winter, an air-conditioned house in summer, a roof over our heads and food on the table every day - I enjoy that lifestyle only because many things are out-of-joint, and capitalism has removed from my sight the unpleasantness of most of the exploited labor and ecological damages on which my lifestyle depends.

So if the play heightens our awareness of moral ambiguity by having the ghost of the dead king mention his "foul crimes" and lazar-like skin, it may be exactly what we need.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

INDEX OF POSTS IN THIS SERIES ON THE RICH MAN AND LAZARUS:

See this link:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2021/02/index-series-on-rich-man-and-beggar.html

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hamlet quotes: All quotes from Hamlet (in this particular series on The Rich Man and Lazarus in Hamlet) are taken from the Modern (spelling), Editor's Version at InternetShakespeare via the University of Victoria in Canada.

- To find them in the first place, I often use the advanced search feature at OpenSourceShakespeare.org.

Bible quotes from the Geneva translation, widely available to people of Shakespeare's time, are taken from an internet source somewhat close to their original spelling, from studybible.info, and in a modern spelling, from biblegateway.com.

- Quotes from the Bishop's bible, also available in Shakespeare's lifetime and read in church, are taken from studybible.info.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

YOU CAN SUPPORT ME on a one-time "tip" basis on Ko-Fi:

https://ko-fi.com/pauladrianfried

IF YOU WOULD PREFER to support me on a REGULAR basis,

you may do so on Ko-Fi, or here on Patreon:

https://patreon.com/PaulAdrianFried

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Disclaimer: If and when I quote or paraphrase bible passages or mention religion in many of my blog posts, I do not intend to promote any religion over another, nor am I attempting to promote religious belief in general; only to explore how the Bible and religion influenced Shakespeare, his plays, and his age.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

My current project is a book tentatively titled Hamlet’s Bible, about biblical allusions and plot echoes in Hamlet.

Below is a link to a list of some of my top posts (“greatest hits”), including a description of my book project (last item on the list):

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2019/12/top-20-hamlet-bible-posts.html

I post every week, so please visit as often as you like and consider FOLLOWING.

To find the FOLLOW button, go to the home page: https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/

see the = drop-down menu with three lines in the upper left.

From there you can click FOLLOW and see options.

Paul,

ReplyDeleteThis might be of some interest regarding Lazarus. https://www.jewfaq.org/olamhaba.htm

Interesting! I agree with your source, from my own theology background, that the idea of an afterlife was a late development, perhaps in response to times of suffering. Witness the suffering of the innocent, just, and kind, and witness how the guilty sometimes get away with their wrongdoing and enjoy the spoils of their injustices, and it's easy to hope and hunger for some form of correction that might come in an afterlife.

Delete"...the ongoing process of tikkun olam, mending of the world." I have also read of this in relation to the work of social justice activists and nonviolent demonstrators. I like the idea.

"...humanity is capable of being considered righteous in G-d's eyes, or at least good enough to merit paradise after a suitable period of purification."

"Gehinnom" sounds a bit like purgatory.

But as I've said of Hamlet, the best time for purification is in this life, not in the next (hence the prince must reconcile with Laertes, and give his dying voice to Fortinbras - if there is anything the prince might do to help get his father out of "purgatory," these two acts might do more than paying for a hundred masses to be said, and perhaps even more than killing a hundred murderous usurpers?)

It is interesting that the period spent in Gehinnom is no more than 12 months, and how that coincides with the idea of a traditional mourning period of a year (before, say, remarriage). It's perhaps not that it takes a soul (or G_d) that long to purify, but it takes the survivors time to process the loss, and to consider the difference that the life of the deceased made to them and to the world?

Many things we project onto religion are about human processes: I once heard it phrased, "Metaphysics reinterpreted as phenomenology." Ha. Someone always needs it translated into jargon, for someone's doctoral thesis committee. ;-D