Part 1: Hamlet Before Freud ("Tough Love" for Gertrude and Ophelia)

If we take seriously that Hamlet, Horatio and the sentinels saw a ghost from purgatory, [1] then we have to consider this possibility:

Hamlet is harsh with his mother and Ophelia because he thinks he has seen his father’s ghost from purgatory who claims to be there because he had sinned, committed foul crimes. Hamlet doesn’t want the two women he loves most to end up in purgatory like his father, or worse, in hell. He scolds Ophelia and tells her to get to a nunnery; he scolds his mother, tells her to repent of her incestuous marriage, a relationship that began, according to the ghost, with adultery when his father was still alive.

Hamlet feels a duty to be harsh with them because he fears for their eternal fate. If one encountered a ghost from purgatory as Hamlet did, and loved his mother and Ophelia, it makes sense that one might want to warn them, to spare them such a fate. [2]

To be clear, while many in Shakespeare’s time believed in ghosts [3], there were also those who did not, so the portrayal in the play of a ghost from purgatory or a demon in disguise would give expression to the beliefs and fears of some, but would have been beyond belief for others.

Religious belief of some kind was more common in Shakespeare’s time, but has been less so in the centuries that followed. Elizabethans tended to be more indoctrinated to adhere to Christian beliefs.

Since then, and especially since Freud, many readers and playgoers have been indoctrinated to assume that ghosts cannot exist, and that gods are merely projections of human myths, fears, ambitions, [4] and unresolved child-parent conflicts. It is harder to take ghosts seriously or literally.

A Freudian reading of Hamlet as having an Oedipal complex [5] was not an option before Freud invented the idea. But reading Hamlet as Oedipal is common in a modern, more agnostic or atheistic age.

For those who doubt the existence of gods and of ghosts, it is easier to conclude that Hamlet is merely delusional, driven by madness. The idea of an Oedipal complex is a convenient explanation. To them, the ghost is a figment of imagination for Hamlet, the sentinels, and Horatio [6].

A Freudian reading of Hamlet as Oedipal is sometimes described as applying a “hermeneutic of suspicion,” suspecting that characters’ real motives are not those they claim to have, but instead, hidden and related to parental attachments and sexual desire, decoded by Freud via the analogy of Oedipus. [7]

Yet the play asks us to suspend our disbelief, and to imagine that ghosts, purgatory, hell, heaven, and God, or “Providence,” exist. Heavy-handed Freudian interpretations of the play make their Freudian assumptions more important than the text, so instead of reading the play, they “botch the words up fit to their own thoughts” [8], playing out (and projecting) their Freudian assumptions. [9]

~~~~~~~~~

NOTES:

[1] I do not believe in ghosts literally, but I do take the idea seriously as figurative in literature and film. Shakespeare’s England was haunted by many ghosts: Past monarchs whose thrones were usurped, people in the line of succession who were poisoned (such as Lord Strange), Catholics who were executed, including Thomas More and John Forest (Franciscan confessor of Catherine of Aragon), Protestants burned at the stake as heretics by Mary I, and Catholics executed as treasonous, as well as many others.

[2] It also makes sense that Hamlet might not reveal to Ophelia that he saw a ghost, or she might think him crazy, or that she might reveal, or be endangered by, knowing the Hamlet’s secret, that Claudius poisoned Hamlet’s father.

[3] Mostly Catholics in Shakespeare’s time were those who considered that ghosts might visit from purgatory. Catholics and Protestants both thought that ghosts might be demons in disguise sent to tempt the living.

[4] In fact, the idea that gods are human projections is very old. From the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

“Xenophanes of Colophon was a philosophically-minded poet who lived in various parts of the ancient Greek world during the late 6th and early 5th centuries BCE. He is best remembered for a novel critique of anthropomorphism in religion [...]

[Fragment] B15 adds [...], that

if horses and oxen had hands and could draw pictures,

their gods would look remarkably like horses and oxen.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/xenophanes/

[5] Freud (Interpretation of Dreams, 1899) introduced the idea of Hamlet as having an Oedipal complex, which Ernst Jones later elaborated: “Jones' investigation was first published as "The Œdipus-complex as an Explanation of Hamlet's Mystery: A Study in Motive" (in The American Journal of Psychology, January 1910); it was later expanded in a 1923 publication; before finally appearing as a book-length study (Hamlet and Oedipus) in 1949.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hamlet_and_Oedipus#Analysis

[6] In a Freudian reading, Hamlet is envious of his uncle for getting the throne, and for marrying Gertrude. Hamlet, like all boys, had fantasies of replacing his father, killing him if necessary. He felt too guilty about such feelings to act on them. Claudius killed Hamlet’s father for him, so now Claudius is a new father figure that Hamlet hesitates to kill. Hamlet is harsh with his mother in her closet because he wants to control her, dominate her and replace his father, but feels guilty doing so.

But it strains credibility to assume that Horatio and the sentinels, who see the ghost first, also share Hamlet’s Oedipal complex, or that they happen to have their own in such a manner that it allows seeing apparitions simultaneously later with the prince.

[7] Applying a “hermeneutic of suspicion” and imagining Hamlet with an Oedipal complex is a very modern thing, perhaps a necessary thing: As time goes on, perhaps lies by powerful people and corporations become more sophisticated, accepted, and commonplace, and for survival, more suspicion of stated motives is necessary?

[8] This is what a "gentleman" or Horatio says in Hamlet 4.5.12 regarding people's reception of Ophelia's "mad" words. All references to Hamlet are to the Folger Shakespeare Library online version: https://shakespeare.folger.edu/shakespeares-works/hamlet/entire-play/

[9]Richard Strier: “I want to argue for the desirability of approaching individual texts with as few presuppositions—theoretical and historical—as possible. The more that the critic knows in advance what a text must or cannot do, the less reading, in the strong sense, will occur.” (2)

“Differing interpretations of a text generally share a large number of particular agreements before they part company. And when they part company, they are still responsible to the features—I would call them facts—that they share. Interpretive conclusions, even widely held ones, do not become facts. That Hamlet delays in killing Claudius is a fact. That Hamlet is neurotic (or whatever) in doing so is not.” (3)

From the book,

Resistant Structures: Particularity, Radicalism, and Renaissance Texts,

by Richard Strier, Number 34 in the series, The New Historicism: Studies in Cultural Poetics, Stephen Greenblatt, General Editor. (Berkeley, California: Univ. of Calif. Press, 1995), pp. 2-3.

IMAGES:

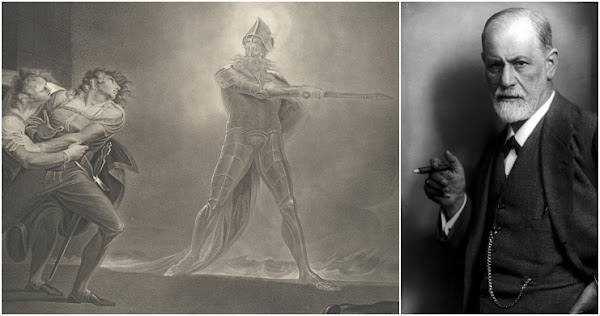

Notice that the ghost of Hamlet’s father is holding a phallic symbol, a sword, pointed toward the photograph of Sigmund Freud, holding a phallic symbol, a cigar, pointing generally toward the phallic regions for Hamlet and the ghost. On this point, the saying apocryphally attributed to Freud is, “Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.” But we might safely assume that if Freud ever said it, he was sublimating.

Left: Title: Hamlet, Horatio, Marcellus and the Ghost (Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 1, Scene 4)

Series/Portfolio: The American edition of Boydell's Illustrations of the Dramatic Works of Shakespeare

Engraver: Robert Thew (British, Patrington 1758–1802 Stevenage)

Artist: After Henry Fuseli (Swiss, Zürich 1741–1825 London)

Originally published by John & Josiah Boydell (British, 1786–1804)

First published 1796; reissued 1852

Pubic Domain, via The Met:

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/365584

Right: Sigmund Freud, founder of psychoanalysis, holding a cigar. Photographed by his son-in-law, Max Halberstadt, c. 1921

Public Domain, via The United States Library of Congress and Wikimedia

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sigmund_Freud_LIFE.jpg

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Disclaimer: If and when I quote or paraphrase bible passages or mention religion in many of my blog posts, I do not intend to promote any religion over another, nor am I attempting to promote religious belief in general; only to explore how the Bible and religion influenced Shakespeare, his plays, and his age.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

My current project is a book tentatively titled Hamlet’s Bible, about biblical allusions and plot echoes in Hamlet.

Below is a link to a list of some of my top posts (“greatest hits”), including a description of my book project (last item on the list):

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2019/12/top-20-hamlet-bible-posts.html

I post every week, so please visit as often as you like and consider subscribing.

To find the subscribe button, see the = drop-down menu with three lines in the upper left.

Comments

Post a Comment