TRANSCRIPT: Presentation for Post Graduates, N.S.S. College, Kerala, India, 7 December, 2023

TRANSCRIPT: Presentation for Post Graduates, N.S.S. College, Kerala, India, 7 December, 2023

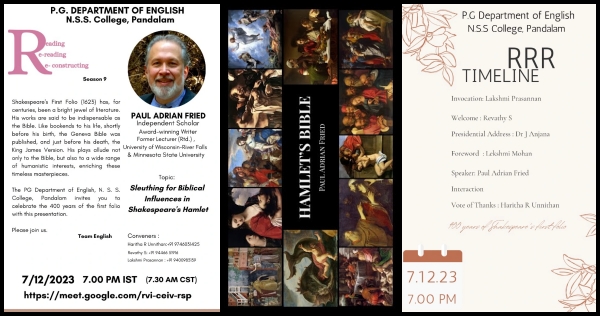

Edited planned transcript of remarks delivered on 7 December, 2023, in an online presentation for the Post Graduate program, N.S.S. College, Kerala, India, 7 P.M. IST, 7:30 A.M. CST.

(A few words and points below were cut from the live presentation for time considerations, and I made a few additional extemporaneous remarks, but for the most part, this is the transcript.)

(I did not have time to talk about allusions that fit into the theme of orphaned children who find transcendent parents in others or in a heavenly parent, but perhaps some other time....)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Informal outline (followed by transcript):

INTRODUCTION: [Disclaimers]

- Contested times, contested scripture

LIST OF BOOKS cataloging Bible allusions in Shakespeare, some open-access:

Sleuthing scripture allusions in Hamlet

CHANGE THOSE NAMES WITH YOU: Servant-Prince, & Renunciation of Fruits

DOUBTING THOMAS (introduced in 1.1)

HEROD ANTIPAS, SALOME, and JOHN THE BAPTIST

JONAH ECHO in Hamlet’s sea-voyage

DELICATE AND TENDER (insult, not compliment)

PRODIGAL (read whole Bible tale)

JEPHTHAH and FORTINBRAS (read whole bible tale)

AMAZE AND ASTONISH (two words plus very ironic echoes)

Three hospitality tales:

1. “WHEN YOU ARE DESIROUS TO BE BLEST, I WILL BLESSING BEG OF YOU”

2 & 3: TWO MORE HOSPITALITY TALES: TWO FACES TO THE SAME COIN

(Tragic vs. happy/comedic endings)

Tragic:

2.a. THE RICH MAN AND THE BEGGAR LAZARUS /

2.b. THE OWL WAS A BAKER’S DAUGHTER

- Horatio’s hunch in 1.1: the ghost having “uphoarded” treasure in the earth;

- Hamlet scolding Polonius for being inhospitable to the players

- Ophelia’s allusion to Robin Hood

- Horatio 5.2 compares compares Hamlet to the beggar Lazarus (Requiem Mass allusion)

Happy/Comedic:

3. THEOXENY TALES: OVID & EMMAUS

Ophelia: “God be at your table.”

Ovid, Zeus and Hermes visit Baucis and Philemon

EMMAUS PLOT ECHO IN GRAVEYARD SCENE 5.1

OPHELIA alludes to both tragic and comedic hospitality tales

GRAVEYARD SCENE WITH CLOWN AS CAREFUL, IMAGINATIVE,

POSSIBLY HERETICAL REINTERPRETATION OF EMMAUS TALE

Thanks!

~~~~~~~~~~

TRANSCRIPT:

Edited transcript of remarks delivered on 7 December, 2023, in an online presentation for the Post Graduate program, N.S.S. College, Kerala, India, 7 P.M. IST, 7:30 A.M. CST.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thank you to the college and your president, the English Department, administrators, technical staff, conveners, Haritha, Revathy and Lakshmi, and especially to Haritha for her kind and cordial invitation, her infectious enthusiasm, and her clear and helpful communication.

Instead of speaking extemporaneously (at the risk of going overtime), I will be reading my remarks, and will also make a transcript of my planned remarks available on my blog,

with links to resources and related blog posts that explore today's topics in greater detail.

Two disclaimers:

First, to make clear who I am, and who I am not:

I have B.A. in English and Theology and an MFA in English and Creative Writing, not a PhD in Shakespeare or Early Modern Literature. During my twenty-some years of teaching, and even more so after retiring, I made it a hobby to study Shakespeare and Religion, especially Hamlet and the Bible. I have been blogging about these topics once a week weekly since June of 2017.

Although I have presented papers at a number of national conferences, and although some of those same ideas are contained in this presentation, my remarks today and in my blog are not from papers submitted to editorial scrutiny and published in academic journals. Some college and university instructors would therefore discourage quoting from work like mine in academic papers, as a blog like mine represents informal opinion.

Second: It is not my intention to promote any religion over another, nor to promote religious belief in general, but rather, to better understand how religion and the Bible influenced Shakespeare’s work and how that influence seems to have manifested itself in his plays.

With those considerations in mind…

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Contested times, contested scripture

It is said that Shakespeare lived in “contested” times, when Protestants, Puritans, Catholics and others argued about how to interpret scripture, relating not only to the Mass and the Last Supper’s words, “This is my body,” but also saints, martyrs, intercessory prayer, and issues like whether purgatory exists, whether a priest is needed to confess sins, and whether churches and homes should be adorned with paintings and statues, perhaps “graven images” prohibited in commandments allegedly given by God to Moses.

Hamlet was written and first published very near the time of the death of Elizabeth I. The queen had not announced an heir, and had made it against the law to publicly discuss who might, or should, become England’s next monarch. This law was also contested.

- “Who’s there?” (the first words of the play) have been said to be interestingly similar to, “Who’s th’ heir?” Some Catholics hoped Mary, Queen of Scots, a Catholic, would follow Elizabeth.

- Before his death, suspected by poison, Lord Strange, Ferdinando Stanley, had a playing company, The Lord Strange’s Men, in which many of Shakespeare’s fellow players had been members. These players may have known his family tree made him and his mother possible heirs to the throne. The word “Strange” appears often in Hamlet, especially Act I, and this underscores a possible connection between the question of England’s heir, the lack of hospitality to the “stranger,” the possible manipulation of succession by poison (a theme in the play), and the biblical command to welcome strangers.

See blog post:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2021/04/welcome-lazarus-lord-stranges-men-for.html

People in Shakespeare’s lifetime were avid readers of the Bible in the mother tongue, because this had long been denied them by Roman Catholicism and its Latin translation of the Bible. Citizens were required to attend English Protestant church services or face fines and possibly suspicion of treason, punishable by death. Such punishment could involve being “drawn and quartered”: hanged until nearly dead, then cut open and shown one’s own intestines, and one’s body cut into quarters to be displayed in various corners of the land, and one’s head placed on a spike on London Bridge. (Doesn’t sound very Christian!)

See blog post:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2023/03/see-inmost-part-of-you-gertrudes.html

With all of this interest in the Bible and religious disputes, and possible suspicion of government hypocrisy for lack of tolerance and mercy, it should come as no surprise that Shakespeare might allude to scripture often in his plays, and especially in Hamlet, with its question of who’s the rightful heir, and the recurrent Bible theme of who gets the birthright, or who the prophet of God claims is the rightful king. Shakespeare is often noted as alluding more often to scripture than any other playwright of his time, and in part perhaps because Hamlet is so long, it has been noted to contain more of these allusions than any of his other plays.

LIST OF BOOKS cataloging Bible allusions in Shakespeare, some open-access

Since the mid-1800s, a number of books have been published that attempt to comment on and sometimes catalog at least the most obvious of Shakespeare’s biblical allusions. Two of the earliest books of this kind were published within five years of when Charles Darwin published his major work, "On the Origin of Species" (1859). Here are some that mention Hamlet:

Thomas Ray Eaton - Shakespeare and the Bible (1858)

https://archive.org/details/shakespeareandb00eatogoog/page/n8/mode/2up?q=Hamlet

Charles Wordsworth - Shakespeare's Knowledge and Use of the Bible (1864) *

https://archive.org/details/shakespeareskno00wordgoog/mode/2up?view=theater

William Burgess - The Bible in Shakspeare (1903) *

https://archive.org/details/bibleinshakspear00burg/page/n3/mode/2up?view=theater

Thomas Carter - Shakespeare and Holy Scripture, with the version he used (1905) *

https://archive.org/details/ShakespeareAndHolyScripture/page/n5/mode/2up

Richmond Noble - Shakespeare's Biblical knowledge and use of the Book of common prayer... (1935)

Peter Milward - Biblical influences in Shakespeare's great tragedies (1987)

Naseeb Shaheen - Biblical References in Shakespeare's Plays (1999)

Hannibal Hamlin - The Bible in Shakespeare (2013)

Shaheen finds about 100 passages in Hamlet that may allude to an even larger number of verses in the Bible, or lines from The Book of Common Prayer, or official sermons.

Sleuthing scripture allusions in Hamlet

I want to share with you today some of my favorite biblical allusions or plot echoes in the play, and tell some stories of how my mind was working, and conclusions I reached about finding allusions. Many of these, or at least some of their ramifications, have not been identified by the major authors of reference books that attempt to catalog biblical allusions in Shakespeare’s plays

CHANGE THOSE NAMES WITH YOU:

Servant-Prince, and Renunciation of Fruits

Late in Act 1, scene 2, Horatio enters with Marcellus and Bernardo. Hamlet doesn’t expect or notice Horatio at first, who seems to have surprised him by coming to Elsinore Castle on his own initiative, to pay his respects on the occasion of the death of Hamlet’s father. Horatio calls his friend Hamlet “My lord,” because Hamlet is the prince, and Horatio offers himself to his friend as “Your servant ever.”

Hamlet replies, “Sir, my good friend- I'll change that name with you.” (1.2.169 [Folger])

Of the five major authors of reference books cataloging biblical allusions in Shakespeare (C.Wordsworth, T. Carter, R. Noble, P. Milward, and N. Shaheen), only one of these, Milward, noticed that this echoes an important biblical theme.

Hamlet corrects Horatio, calling Horatio his “good friend” and offering not only to call Horatio good friend instead of servant, but also to exchange the name “servant” with Horatio, so that Hamlet would be servant to his friend. // This echoes Jesus saying that those who would be first must be last and servant to all, and in one gospel, Jesus washes the feet of the disciples to demonstrate and symbolize service.

For a prophet of God and teacher to wash his students feet, or for a prince to aspire to be servant, implies a form of renunciation of fruits, to which the motto of your college refers in the Gita, as Haritha kindly translated the relevant passage for me. And service is part of your college’s name, in the initials, N.S.S.

This allusion is, I believe, quite important, and reveals something about Hamlet’s character before he is tempted by the ghost to revenge.

TAKEAWAY:

The words “I'll change that name with you” may seem commonplace, perhaps unworthy of close scrutiny, but sometimes biblical allusions or plot echoes can be found in the commonplace.

Blog link on this topic:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2017/05/hamlet-as-servant-prince-paraphrased.html

~~~~

DOUBTING THOMAS: Horatio (and belief or doubt in Hamlet, Polonius, and Gertrude)

When I was first invited to speak online at a college in Kerala, I did some research on Kerala and on your college’s founder, and it turns out that one allusion in the very first scene of the play points to a historical figure mentioned in John’s gospel, with connections to Kerala:

It is said that Thomas the apostle traveled to India and established a church there, and there was some controversy related to that church during the career of your college’s founder. (I am no expert on that history, but it was worth noticing for this connection).

In Act 1, scene 1, before the ghost appears, Marcellus says Horatio won’t believe that they’ve seen a ghost: He is a skeptic.

The ghost appears, frightens them, and Horatio, having seen it himself, shifts from disbelief to belief. This clearly implies that Horatio a kind of doubting Thomas, but the ghost is not the risen Jesus, perhaps a malevolent figure, so biblical allusions in Shakespeare are often complicated.

Shakespeare will often use and then discard an analogy, or perhaps use it in such a way to highlight contrast and create cognitive dissonance: Horatio is a doubting Thomas, but the ghost is either a demon in disguise, or at least a soul in purgatory for foul crimes, unlike Jesus.

Marcellus says they’ve already seen the ghost twice before, which corresponds to the gospel story in which the women see the risen Jesus first, and then the disciples, and then in John’s gospel alone, having missed out on the first two appearances, Thomas witnesses the third.

This corresponds to the play: The ghost in the play appears twice, then to Horatio on the third time. Doubting Thomas.

But strangely, this connection is not mentioned by five major authors of reference works on Bible allusions in Shakespeare, Bishop C. Wordsworth, T. Carter, R. Noble, P. Milward, and Shaheen.

Although these lines do not use the name “Thomas” or the word “doubt,” the context, the previous appearances, and the word “belief” echo Thomas in John’s gospel.

At the end of this encounter, Jesus says, “Thomas, because thou hast seen me, thou believest: blessed are they that have not seen, and have believed.” (John 20:29)

Until recently, I had not realized: Hamlet doesn’t doubt Horatio’s word about the ghost.

When Horatio tells Hamlet, I think I’ve seen your father, Hamlet doesn’t say, “No way!”

“...blessed are they that have not seen, and have believed.”

Whereas in the next scene, Act 1, scene 3, Laertes and Polonius distrust the motives of Hamlet and his vows to Ophelia, we might note that Hamlet’s trust here in Act 1, scene 2, may show that he is more trusting than the skeptic Horatio. In fact Hamlet is initially quite trusting of the ghost, but perhaps Hamlet benefits the second opinion of his skeptical friend, the way the parts of the body need one another, as the Christian scriptures say.

Also, Gertrude enacts the lesson of the tale that Jesus offers, that of not seeing yet believing, when she tells of Ophelia’s drowning as a kind of good death, a death-in-faith, true to faith.

Gertrrude does not say whether she was an eye witness of the drowning, or heard it from others;

The drowning of Ophelia is not enacted on stage, so WE are not eyewitnesses..

Gertrude tells her account and asks characters on stage (and us, perhaps)

to accept that account “on faith,” without witnessing a staged drowning of a faithful Ophelia.

Gertrude may have made up the story out of kindness,

to spare Ophelia the indignity of a suicide’s funeral,

or out of prudence, to prevent Laertes from a new tantrum or rebellion.

So she asks us to believe her, without seeing,

to trust either her truthfulness, or her kindness and prudence as queen and fellow Christian.

So to summarize:

- In Act 1, scene 1, the initial allusion is acted out with Horatio as doubting Thomas;

- In Act 1, scene 2, Hamlet believes Horatio about the ghost, taking him on faith, without seeing, and soon, he will also take the ghost at his word, at least at first, but will seek proof of the ghost’s honesty by way of The Mousetrap.

- In Act 1, scene 3, Laertes and Polonius doubt Hamlet's intentions toward Ophelia

- in Act 4 scene 7, belief without seeing is invited of all spectators by Gertrude:

“...blessed are they that have not seen, and have believed.”

For more, see this blog post:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2020/01/doubt-thomas-hamlet-reduct-rabbit.html

TAKEAWAY 1:

It is far easier to recognize the first allusion, with Horatio’s disbelief changed to belief,

than with Hamlet believing, or with Queen Gertrude asking us to take her at her word, in faith.

TAKEAWAY 2: IT’S COMPLICATED

The allusion to doubting Thomas doesn’t mean the ghost is the risen Jesus. He seems malevolent and vengeful. So just because an allusion is there doesn’t mean it will be simple: it may be ironic, to highlight contradictions and create cognitive dissonance.

TAKEAWAY 3: the art of sleuthing for biblical allusions may involve finding a more explicit allusion in one spot, and then seeking other less explicit connections in actions of other scenes, or even - like some Freudians - viewing a scene or the play itself through the lens of a biblical tale (instead of a Greek one like Oedipus or Orestes).

~~~~~

HEROD ANTIPAS, SALOME, and JOHN THE BAPTIST:

ANOTHER EXAMPLE where an allusion is explicit in one spot but pops up elsewhere…

There is a biblical tale about how John the Baptist had condemned the incestuous marriage of Herod Antipas to his brother’s divorced wife. Her daughter, Salome, danced for King Herod in a way that pleased him so much that he promised her any wish, up to half his kingdom, to reward her. At her mother’s bidding, she asked for the head of John the Baptist who had condemned the marriage.

This is echoed in scattered references, most obviously when Hamlet uses the name Herod,

and names the player queen in the play-within-the-play as “Baptista,”

but also perhaps in Ophelia acting as bait for Claudius and Polonius’ spying,

and Hamlet speaking of how women jig and amble (dance). Note also:

Claudius in Act 1 scene 2 asks Laertes what he could possibly ask that he would not be willing to give to the son of his trusted advisor,

and later in the play after Laertes’ angry return from France, promising Laertes his whole kingdom

if Laertes can prove Claudius had anything to do with the death of Laertes’ father.

Laertes and Ophelia figuratively dance for the king: they do his bidding, like Salome.

See blog posts:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2018/10/in-hamlet-do-laertes-ophelia-echo.html

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2018/11/hamlet-footnotes-in-need-of-updates.html

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2018/11/hamlet-which-herod-which-baptista-in.html

Again, the takeaway:

More explicit references in certain places might lead one to notice less explicit ones elsewhere.

ANOTHER TAKEAWAY:

Some critics think the herod allusion can only point to Herod the Great,

who slaughtered the innocents in the Jesus infancy tales,

and some think “Baptista” is not a reference to John the Baptist, because to them,

that might make the play and its author seem more religious than they’d prefer.

So sometimes identifying possible biblical allusions may mean disagreeing

with what some assume should be scholarly consensus.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

JONAH - and Hamlet's sea-voyage

The next allusion I want to talk about

I would not have noticed if a student in my literature class

had not asked me to display on the class screen

a map showing England’s distance from Denmark,

so he could better understand Hamlet’s sea voyage.

I looked at the screen and showed how, sometime before they got to England,

Hamlet switched from that first ship to a pirate ship, which took him back to Denmark.

I thought: JONAH and the fish!.

Because I had studied theology and the Bible as well as English for my B.A., I had seen maps of Jonah’s voyage, of how the prophet was supposed to go a bit north-east to Nineveh, but instead he tried to go more than three times that distance westward, to Tarshish, like the western edge of the known world. - but after a storm, Jonah asked to be thrown overboard, and was swallowed by a fish.

I felt certain that scholars over the last four centuries must have noticed this similarity in the sea voyages of Hamlet and Jonah, and the fact that both Jonah and Hamlet change mode ot transportation mid-sea, Jonah swallowed by a fish, Hamlet figuratively swallowed by a pirate ship.

But I found no scholars who spoke of Hamlet’s voyage as a kind of Jonah parallel, although I did find some helpful information on another play, a decade or two before Shakespeare’s Hamlet, a play called A Looking Glass for London, which (like Hamlet) had

(1) a theme of an incestuous marriage, and

(2) Jonah himself as a character in the play.

The Jonah echo also brings to mind how in the gospels Jesus claimed he would be put to death and rise again. He refers to this as “the sign of Jonah”:

The prophet was in the belly of the fish, like Jesus in the tomb for three days.

Jonah had to repent of his running from his destiny,

perhaps as Hamlet had to face his destiny in some better way,

instead of “My thoughts be bloody, or be nothing worth!” (4.4)

Five blog posts related to this:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2018/04/the-ghost-of-jonah-haunts-hamlet.html

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2022/04/hamlets-sea-voyage-christ-in-tomb-and.html

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2022/05/hamlets-unnamed-ghost-of-jonah-and.html

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2022/05/the-elizabeth-jonas-and-hamlets-sea.html

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2020/03/two-late-eliz-plays-royal-incest-jonah.html

TAKEAWAY:

Just because scholars ignore or downplay the importance of a part of a text,

that doesn’t mean you have to go along with them. They may have missed something important.

And just because the words “Jonah” and “fish” are not used in the play regarding Hamlet’s voyage,

that doesn’t mean the plot echo isn’t there. It clearly is, but it’s obscured.

As Theseus says in “A Midsummer Night's Dream,”

“...as imagination bodies forth / The forms of things unknown, the poet's pen /

Turns them to shapes and gives to airy nothing / A local habitation and a name.”

Shakespeare takes essential plot elements of the Jonah tale and gives them

a new local habitation and names in Hamlet’s sea voyage.

~~~~~

DELICATE AND TENDER

Next, I want to show how a small correction in understanding through identifying a biblical allusion might correct a commonly held scholarly misunderstanding with larger ramifications for the meaning of the play.

I am a fan of David Bevington’s work, not only in books like Murder Most Foul: Hamlet through the Ages, but also in his editing, which you may already have enjoyed if you ever accessed the Internet Shakespeare Editions through the University of Victoria.

But in my reading of Bevington, I came across a passing reference to how Hamlet, in Act 4, scene 4, calls Young Fortinbras a “delicate and tender” prince. It’s a small, passing reference, and many scholars assume this is a compliment, perhaps saying Fortinbras is not a harsh and stone-hearted prince, but a kind one.

But in fact, in the Bishop’s bible, read in church in Shakespeare’s time, Deuteronomy 28:54-57 describes a “delicate and tender” man and woman who fail to follow Mosaic law, pamper themselves, neglect spouse and children, and who, if the city were under siege, would eat their own children: So it turns out that “delicate and tender” is not a compliment at all, but a sarcastic insult, like calling someone pampered, spoiled, and too entitled.

In Luke 16:19, in the Geneva translation of the tale of the Rich Man and Lazarus, the hell-bound rich man is described as faring “well and delicately every day.” He is pampered and spoiled while neglecting the beggar Lazarus.

This allusion was missed by three of the four major authors of reference books on Bible allusions in Shakespeare, caught only by Shaheen, who also notes the phrase “delicate and tender” in Isaiah 47:1. But Bevington and many others missed it.

This is important, because if we assume incorrectly that Hamlet gives Fortinbras a compliment here, that colors our understanding of why Hamlet decides to give Fortinbras his dying voice

as the next king of Denmark.

If it’s NOT a compliment, then Hamlet chooses him IN SPITE of certain perceptions of him, and not out of admiration.

This scholarly misunderstanding might have been cleared up by simply googling three words:

< Bible / delicate / tender >

This would lead right to the Deuteronomy passage.

See blog post:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2018/11/to-hamlet-delicate-tender-isnt-about.html

TAKEAWAY:

Even small phrases and words can convey biblical allusions,

and the implications can be enormous,

so if something seems strange in the text, trust your instincts and check reference books,

or do a web search for biblical phrases.

~~~~~

PRODIGAL - the importance of one word

In Act 1, scene 3, Laertes uses the word “prodigal” to warn his sister Ophelia about protecting her chastity and not to get too involved with Hamlet. She says she’ll remember his advice, but warns him not to go off to France and be a hypocrite regarding his own chastity.

Later in the same scene, she tells her father Polonius that Hamlet made to her “Almost all the holy vows of heaven,” and he dismisses this, claiming I do know, / When the blood burns, how prodigal the soul / Lends the tongue vows.” (So he’s accusing Hamlet of being a prodigal for making perhaps insincere vows to her.)

Both Laertes and Polonius use the word “prodigal” to frighten and shame Ophelia so as to control her sexual behavior.

But it occurred to me about four years ago that the heart of the gospel tale of the prodigal son

is not about shaming people or calling them prodigal, but about the father who mercifully and generously welcomes the wayward son home.

Perhaps the best example of a merciful and generous parent in the play might be if we were to read Gertrude in the last scene as being secretly suspicious that the chalice from which Hamlet is meant to drink might be poisoned, and without saying so, volunteering to test it, then disobeying her husband Claudius when he tells her not to drink.

That scene is sometimes played that way, with Gertrude suspecting poison.

Blog post related to this topic:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2019/01/getting-prodigal-wrong-in-hamlet-13.html

TAKEAWAYS:

1. Every word matters.

2. Read the whole Bible tale when you find an allusion,

and see if an important echo of the rest of the tale

might be found in some other part of the play.

3. Notice that the word “Prodigal” sort of rhymes with “Oedipal,” and if you swap the R and G in Prodigal for an E, you could spell Oedipal. So Prodigal is Oedipal spelled badly. 😉😜

- But more seriously: Instead of reading the play through Freud’s Oedipal lens, one could read the play through the lens of many of the biblical allusions, such as the tale of the prodigal son, or other biblical tales I discuss today.

~~~~~

JEPHTHAH

Hamlet calls Polonius a “Jephthah” by reciting lines from a poem or song about him, and much has been said about this, as Jephthah is a biblical character who made a bad oath and then felt he had to keep it by ritually sacrificing his daughter.

Sermons of the time discouraged bad oaths, and scholars connect this allusion to William Cecil and the Bond of Association, whereby English nobles swore that should Elizabeth be assassinated, or attempts made on her life, they would avenge her. Vengeance as something promised in an oath goes against Christian ideals of forgiveness and of loving one’s enemies. So some believed the Bond of Association was a bad oath.

But if one reads the whole Jephthah tale, one finds many correlations with details we learn about Young Fortinbras in Act 1, scenes 1 & 2:

he was a kind of orphan, or suffers a type of interrupted parentage, as did Jephthah;

he was aggrieved about a loss of his family’s land or inheritance, as did Jephthah;

he pestered his opponent with messages asking for return of the land, as did Jephthah;

he recruited lawless resolutes, as did Jephthah;

he gets the throne or high position of authority in the end, as did Jephthah.

Many claim Fortinbras, prince from the north who inherits the throne by someone’s dying breath,

is like James, prince from the north, who succeeded Elizabeth perhaps in her figurative dying breaths.

But this would imply that Shakespeare is subtly, indirectly, alluding to James as an ambitious Jepthah figure, or at least a potential maker of bad oaths for which some people may eventually have to suffer.

This is a politically charged angle to the Jephthah allusion and Fortinbras correlations with which some scholars would certainly disagree, but still, worthy of consideration.

More on Jephthah and Fortinbras:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2021/02/fortinbras-jephthah-james-stealthy.html

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2020/12/jephthah-polonius-cecil-ambitious.html

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2021/01/gertrude-ghost-as-jephthahs-loss-of-eden.html

Takeaway: Again,

read the whole scripture tale when you find an allusion and look for other correlations.

They might be important.

~~~~~

AMAZE AND ASTONISH

I want to briefly mention an allusion I spotted in Hamlet less than a year ago, one that comes just after The Mousetrap, after Claudius and Gertrude have left the room.

Guildenstern comes to Hamlet and they have some humorous misunderstandings, almost like a comedy routine, where Guildenstern is the straight man, and Hamlet cracks the jokes.

Guildenstern says Hamlet’s behavior has struck Gertrude “into *amazement* and admiration.

Hamlet replies, “O wonderful son that can so [a-]’stonish a mother!”

This is actually an allusion to the story of the boy Jesus, lost on a trip to Jerusalem, and found at the temple, speaking with the temple elders, who, with his mother, are “astonished” and “amazed” at this remarkable boy.

This is a very ironic allusion. Hamlet, like Jesus who has a step-father Joseph, also has a step-father, his uncle Claudius.

In catching the conscience of the king, Hamlet thinks he is like the boy Jesus, astonishing and amazing all who look on.

But Hamlet is doing this to find justification for killing his uncle, and will soon accidentally stab and kill the father of his beloved Ophelia, thinking it’s Claudius. This is not something Jesus would do.

For more on this topic, I did a 12-part series of blog posts that begins here:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2023/01/hamlet-as-boy-jesus-among-synagogue.html

Takeaway:

Although the main scholars in this field missed this,

pay attention to words and context that may echo something in a Bible tale.

And don’t let ironic twists like this one distract you from the allusion.

~~~~~

Next, consider allusions to

three hospitality tales:

1. “WHEN YOU ARE DESIROUS TO BE BLEST, I WILL BLESSING BEG OF YOU”

First, I believe there is a subtle biblical allusion when Hamlet tells his mother in her closet,

“When you are desirous to be blest, I will blessing beg of you”

If she desires to be blest, it would seem counterintuitive and rude

for him to choose that future moment to beg a blessing of HER.

But something about this reminded me of a BIble tale: In first and second Kings,

there are tales of the prophet Elijah visiting a widow and her son or sons.

In one of these, (1 Kings 17:7-16) in a time of famine,

a widow and her son are hungry and near starvation and death.

But the prophet, as if to test her, asks her for a little food.

Remarkably, she does not refuse him this hospitality,

although it may only hasten the death of her son and herself.

He blesses her so that her jar of flour and jug of oil will not run out

until the end of the famine, and this comes true.

For more on Hamlet and 1 Kings 17:7-16, see this post:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2022/11/hamlet-to-gertrude-when-you-are.html

In a later similar tale, (1 Kings 17:17-24) he raises her son back to life,

perhaps correlating to when Hamlet is spared from death on his sea voyage.

For more on Hamlet and 1 Kings 17:17-24, see this post:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2022/12/part-2-hamlet-and-inherited-debt-2.html

In yet another (2 Kings 4:1-7), a widow’s husband died in debt, so her sons are to be taken off

into debt slavery until the debt is paid, but the prophet helps her with a miracle

that allows paying off the debt and sparing the sons from debt slavery.

How does this relate to Hamlet?

The ghost of Hamlet’s father says he died with “foul crimes” on his soul,

and by asking his son to avenge his murder, he is passing that debt to Hamlet.

For more on Hamlet and 2 Kings 4:1-7, see this post:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2022/12/part-3-when-you-are-desirous-to-be.html

But in Gertrude’s actions, expressing solidarity with Ophelia, and delaying her son’s death by poison by drinking from the chalice, and by Hamlet passing the crown to Fortinbras, perhaps the father’s debt is repaid. Hamlet’s father had killed Old Fortinbras, but giving Young Fortinbras the crown is like reparation, as other critics have speculated.

TAKEAWAY:

Even an abstract line like

“When you are desirous to be blest, I will blessing beg of you”

Might convey an allusion to a moment in a biblical tale.

~~~~~

2 & 3: TWO MORE HOSPITALITY TALES (TWO FACES TO THE SAME COIN)

(Tragic vs. happy/comic endings)

Finally, I want to end with two allusions to other hospitality tales: One has a tragic ending, the other a happy ending, so they are like two faces to the same coin.

2.a. THE RICH MAN AND THE BEGGAR LAZARUS /

2.b. THE OWL WAS A BAKER’S DAUGHTER

Tragic ending:

The ghost thinks the poison made his skin “lazar-like,” an allusion to the tale of the Rich Man and the beggar Lazarus in Luke 16:19-31, read every First Sunday After Trinity Sunday, and also read every 5 March, 4 July, and every 30 October as the second lesson for Morning prayer, every year of Shakespeare’s life.

This same tale is retold in folktale form in the story to which Ophelia refers when she says, “They say the Owl was a baker’s daughter.” The baker’s daughter, like the rich man, is ungenerous with a beggar at the door. In the Baker tale, the beggar is Jesus in disguise.

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2021/04/the-begggar-lazarus-at-bakers-door-in.html

In Luke, in the Lazarus tale, the beggar has sores all over his skin licked by dogs, perhaps leprosy. Also in Luke, the rich man and the beggar both die, but Lazarus goes to heaven where he is finally treated well, and the rich man goes to hell, where he suffers in flames, which probably make his skin all full of burn-sores, like the skin of the beggar he neglected.

I think the dead king has “lazar-like” skin, not because of the poison, but because like the rich man, he is being punished by God for ill-treatment and lack of hospitality toward someone who was, without his knowing it, vitally important to his salvation.

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2021/02/new-series-on-rich-man-lazarus.html

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2021/02/if-ghost-was-like-rich-man-who-was-his.html

This is an important allusion because it is repeated:

- in Horatio’s hunch in 1.1. about the ghost being like a person who had “uphoarded” treasure in the earth;

- in Horatio and Hamlet’s frequent use of the words “strange” and “stranger,” pointing perhaps to the (inhospitable!) suspected poisoning of Lord Strange (previously mentioned early in this talk: see above);

- in Ophelia’s folktale “owl” reference:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2023/10/part-17-ophelias-owl-and-false-steward.html

- the theme is present in Hamlet scolding Polonius for not being hospitable toward the players. Polonius assumes he can be judgmental about what sort of lodging the players deserve. Hamlet replies:

God’s bodykins, man, much better! Use every

man after his desert and who shall ’scape

whipping? Use them after your own honor and

dignity. The less they deserve, the more merit is in

your bounty. Take them in. (2.2.555-559 Folger)

- So in other words, Hamlet assumes Polonius should avoid being like the Rich Man was to the beggar Lazarus, and instead be more generous and perhaps avoid the fate of the Rich Man.

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2021/03/beggars-players-ill-report-poloius.html

- the contrast between rich and poor in Ophelia’s allusion to Robin Hood: ““For bonny sweet Robin is all my joy” (4.5.210), as Robin Hood was a trickster who robbed the rich to give to the poor:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2023/10/part-21-ophelias-bonny-sweet-robin.html

Horatio in 5.2 also compares Hamlet to the beggar Lazarus when he alludes to the lines from the Requiem Mass about the angels that bring Lazarus to the heart of Abraham, “angels sing thee to thy rest”:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2021/06/horatio-alludes-to-requiem-mass-lazarus.html

These allusions and phrases all repeat the theme of the rich being hoarders, and neglecting the poor.

But if this is the tragic ending version of the hospitality tale,

what is the happy ending version?

At one point in Act 4, scene 5, Ophelia says, “God be at your table.” There are old Greek and biblical tales, one in Ovid with which Shakespeare was familiar, where gods or angels visit people in disguise, and they are shown hospitality, and later reveal themselves, sometimes at table.

In Ovid, Zeus and Hermes visit an elderly couple (Baucis and Philemon) who are kind and generous with hospitality and food; the gods reveal themselves at table.

This is an example of a theoxeny or theoxenia tale: Be hospitable, for the stranger may be a god in disguise.

EMMAUS WITH CLOWN IN GRAVEYARD

At least five years ago or more, I realized that the graveyard scene with the gravedigger-clown and the discovery of Yorick’s skull echoes a Christian theoxeny tale, the plot of the Emmaus tale.

Instead of two disciples on the road to Emmaus,

two Danes are on the road to Elsinore.

They meet a stranger who does for them many things very much like what a recently deceased important person in their lives had done:

- In the Emmaus tale, the stranger does things like what Jesus had done.

- In Hamlet, the gravedigger-clown does things like what Yorick had done.

- In the Emmaus tale, they recognize Jesus in the breaking of bread,

something that happened at the Last Supper.

- In Hamlet, the moment of recognition comes in a tale of poured wine: The gravedigger tells a tale that reveals he was a drinking buddy of Yorick, who poured a bottle of Rhenish wine on his head -

and pouring wine was another important action at the last supper (as was foot-washing, in response to which Peter tells Jesus that if it must be done, why not wash all of him, head to foot? And Yorick pouring of wine on the sexton/gravedigger’s head echoes Peter also in this way).

- In the Emmaus tale, Jesus seems to have transcendent, divine qualities.

In Hamlet, Yorick was a man of “infinite jest,” as if like a god of fools.

For more on this Emmaus echo in the graveyard scene, see these blog posts:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2018/04/emmaus-plot-echoes-in-shakespeare-when.html

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2018/05/emmaus-in-hamlet-in-emmaus-story-1.html

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2022/05/from-fear-power-to-fools-affection.html

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2022/05/why-rhenish-not-bread-emmaus-in-hamlet.html

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2022/05/hamlet-emmaus-eucharistic-controversy.html

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2022/05/emmaus-key-change-in-hamlet-merchant-of.html

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2023/04/hamlets-emmaus-in-jonahs-belly.html

OPHELIA alludes to both kinds of hospitality tales:

First to the tragic ending version, the owl was a baker’s daughter (4.5.47-48),

then to the happy ending: God be at your table. (4.5.49).

The play is careful not to say all kings are like the rich man, but implies the dead king’s foul crimes may have involved some grave lack of hospitality, like killing Old Fortinbras, or neglecting his brother, wife, and son.

GRAVEYARD SCENE WITH CLOWN AS CAREFUL, IMAGINATIVE,

POSSIBLY HERETICAL REINTERPRETATION OF EMMAUS TALE

But the scene also reinterprets Emmaus, not with an appearance of a supernatural Yorick risen in the graveyard, who can shape-shift, or do Jedi mind-tricks, but rather, with Yorick appearing in a kindred spirit of one of his old drinking friends, a fellow fool and clown: a more natural than supernatural interpretation of the Emmaus tale.

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2022/05/blasphemy-and-heresy-in-hamlets-emmaus.html

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2022/05/heresy-in-hamlet-51-emmaus-figures-part.html

It may have been too heretical and dangerous for Shakespeare to say simply that he did not believe Jesus appeared literally, a resuscitated corpse on the road to Emmaus, but by enacting a naturalistic reinterpretation, it seems to have avoided the censors.

Takeaway: Plot echoes are subtle, but if you think about the structure of stories in the abstract, such as the Rich Man and Lazarus, the Owl and the Baker’s Daughter, and the Emmaus tale, you might spot them, so be on the lookout!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thank you SO MUCH for listening to this presentation.

I have only identified a small number of the many biblical allusions in Hamlet, and hardly scratched the surface regarding their significance, how to interpret the play in light of them.

If you enjoyed my remarks and wish to learn more, please do consult some of the many published works by other authors on Shakespeare and the Bible (list above, earlier in this edited transcript), and feel free to visit my blog, to comment, and subscribe.

Again, within the next day or two, I will be posting my planned transcript of these remarks today on the blog with links and more resources.

Again, my sincerest thanks.

How to find me on LinkedIn:

www.linkedin.com/in/pauladrianfried

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

INDEX OF OPHELIA POSTS:

My 2023 series on Ophelia, and earlier Ophelia posts:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2023/10/index-of-ophelia-posts-2023-series-and.html

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

YOU CAN SUPPORT ME on a one-time "tip" basis on Ko-Fi:

https://ko-fi.com/pauladrianfried

IF YOU WOULD PREFER to support me on a REGULAR basis,

you may do so on Ko-Fi, or here on Patreon:

https://patreon.com/PaulAdrianFried

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Disclaimer: If and when I quote or paraphrase bible passages or mention religion in many of my blog posts, I do not intend to promote any religion over another, nor am I attempting to promote religious belief in general; only to explore how the Bible and religion influenced Shakespeare, his plays, and his age.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

My current project is a book tentatively titled Hamlet’s Bible, about biblical allusions and plot echoes in Hamlet.

Below is a link to a list of some of my top posts (“greatest hits”), including a description of my book project (last item on the list):

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2019/12/top-20-hamlet-bible-posts.html

I post every week, so please visit as often as you like and consider FOLLOWING.

To find the FOLLOW button, go to the home page: https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/

see the = drop-down menu with three lines in the upper left.

From there you can click FOLLOW and see options.

Comments

Post a Comment