In service of art: How visual arts may have influenced the Lazarus theme in Hamlet - part 18

Scholars often think of how texts influence other texts. But what about other arts influencing texts? Some scholars consider this, but it seems that they are not in the majority.

By the time Shakespeare wrote or revised his version of Hamlet for the stage, the Luke 16 tale of the rich man and Lazarus already had centuries of history of being interpreted in many forms, perhaps not only for a folksong-ballad whose origins may be older than Shakespeare,* but also by sculptors and artists.

*(Another reference regarding an Elizabethan version of the ballad, noted by Bronson:

"Bronson (Vol. II, p. 17) writes: "CHILD NO. 56: As Child's note informs us, something on the order of this ballad was in print in early Elizabethan times, and seventy-five years later was still matter for common allusion as 'the merry ballad of Diverus and Lazarus.' No early text survived, how ever, and Child had to resort to nineteenth-century reprinting: of eighteenth-century broadsides for his copy."

<http://mysongbook.de/msb/songs/d/divesand.html>)

The many visual renderings of the Lazarus tale had a rich and remarkable variety. Shakespeare lived in a culture that had inherited a rich legacy of art works which had already explored many possible ways of imagining the tale.

In this multi-part series about the influences of the Lazarus allusion in Hamlet, I have been exploring various incarnations in the play of the theme of the beggar Lazarus, neglected by the rich man. I have considered many scenes where the dynamics seem to place specific characters in the role of beggar or "rich," "have" or "have not," as well as laws relating to beggars and vagabonds, and approved, official sermons that also allude to the beggar Lazarus or the rich man.

But this week, I would like to suggest that diverse works of visual art that rendered this gospel story may have helped Shakespeare feel he had the permission, support, and freedom to explore the theme in its many manifestations in the play as we know it. In this way, it was not only the Biblical text that influenced Shakespeare's play text, but also visual incarnations of the story.

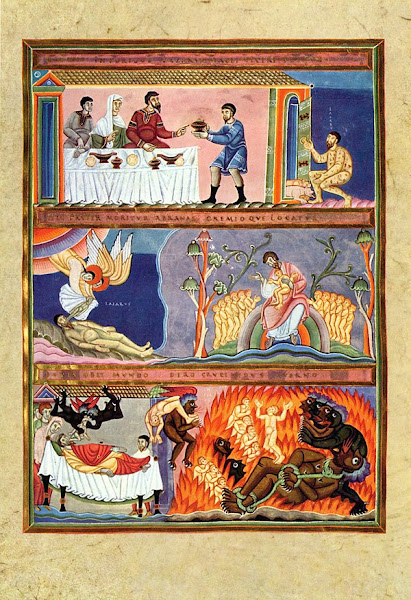

ILLUMINATION FROM THE CODEX AUREUS OF ECHTERNACH, 1035-40

One of the oldest images I've drawn upon in this series appeared in Part 2, an illumination from the Codex Aureus of Echternach, circa 1035-1040. This is made up of three main sections, top, middle, and bottom, each of which is also divided in two. In the top section, the rich man is shown in the larger part at middle and left, while the beggar Lazarus is shown to the right, excluded from the feasting, his sores licked by dogs.

The central section shows, at left, the death of Lazarus, his soul taken by angels, and at right, in heaven with Abraham.

The bottom section shows, on the left, the death of the rich man, his soul taken by demons, and on the right, his torment in hell.

We might note that this follows the apparent structure of the gospel story, but does not include the dialogue in which the rich man asks that Lazarus act as a servant to quench his thirst, or to act as a messenger to his brothers; nor does it explicitly identify the corruption of the Jerusalem priesthood portrayed in the rich man, as discussed in a previous post, informed by biblical research.

[Lazarus and Dives, illumination from the Codex Aureus of Echternach, circa 1035-1040. Public domain. Image via Wikipedia.

Top panel: Lazarus at the rich man's door.

Middle panel: Lazarus' soul is carried to paradise by two angels; Lazarus in Abraham's bosom

Bottom panel: Dives' soul is carried off by Satan to hell; Dives is tortured in hell.]

I do not suggest that Shakespeare ever saw the Codex Aureus of Echternach, but it is very possible that he saw other, similar illustrations of this gospel tale. Seeing an image such as this might nudge a future playwright toward a greater awareness of the structure of the tale.

THREE EXAMPLES FROM ENGLAND

The next three examples I will offer below are from England, from locations shown on the map below, with Stratford to the west, Lincoln Cathedral to the north, Canturbury to the east, and Pittleworth Manor to the south near the estate of Shakespeare's patron, the Earl of Southhampton.

LINCOLN CATHEDRAL FRIEZE PANELS

About 99 miles from Shakespeare's home in Stratford-upon-Avon, Lincoln Cathedral included many frieze panels that illustrated various Biblical tales. One of these (left, below) depicted the feast of Dives, or the rich man, and another (right) depicted (top) Lazarus taken to heaven, and (bottom) the rich man's fate in hell.

[Dr. Alison Stones of Pitt.edu lists the above black and white photograph as from Prior and Gardner (Prior, Edward Schröder. An account of medieval figure-sculpture in England, with 855 photographs, by Edward S. Prior... and Arthur Gardner... Cambridge, University Press, 1912. LC Call Number: NB463.P95. Dr. Stones claims copyright of the digitized images from the 1912 book. Image reproduced here by fair use.]

A more recent, color photograph of the second panel is shown below, depicting the judgment of Lazarus (above) and the rich man (below), being swallowed by a "hell mouth," which is sometimes discussed as a feature of late medieval and Early Modern theater.

Again, there is no way of knowing whether Shakespeare ever saw these panels on Lincoln Cathedral, but he may have, and if not, he may have seen others like it among the various churches of London.

EADWINE PSALTER

The Eadwine Psalter is an illuminated book of psalms that originated at Christ Church, Canterbury, which later became Canterbury Cathedral. It has been dated to around 1155-1160, and contains images relating to the rich man-Lazarus tale. So this dates later than the Codex Aureus of Echternach, and around the same time as the frieze panels on Lincoln Cathedral. [Eadwine psalter - Morgan leaf M.521 (recto) (cropped, Dives and Lazarus). Public domain. Via Wikipedia.]

The system of partitions in this is a bit similar to the Codex Aureus of Echternach, but while it begins with the rich man at his banquet in the upper left, it then shows, in the upper right, the beggar Lazarus, his sores licked by dogs, but also dying and his soul being taken to heaven.

The death of the rich man then has its own section at bottom left, and at bottom right, we see Lazarus in heaven with Abraham (top) and the rich man in hell (bottom). These may seem like small details and differences, but such choices have to be made to translate the story into some form in which it can be recognized in the visual representation.

LAZARUS AND DIVES DINING ROOM MURAL, PITTLEWORTH MANOR, EARLY 1500s

In the 1920s, in an old tudor era home in England, a mural was discovered depicting the story of the beggar Lazarus and the rich man, or "Dives." The mural had been covered over with paneling, but it was fairly well preserved and is thought to have been typical of wall decorations of the period. One wall featured a pomegranate pattern which would have been associated with Katharine of Aragon, first wife of Henry VIII. The owner of the house at the time was a known Catholic and recusant (refusing to take communion in the English Protestant church). The discovery drew great interest and was featured in the November 11 issue of Country Life Magazine.

More discussion of the murals at Pittleworth Manor can be found in a variety of sources, including "Lodging Dwelling Painting: Dives and Lazarus at Pittleworth Manor" by Elizabeth Alice Honig, among the essays in a 2020 book called Explorations in Renaissance Culture published by Brill. [Image 2, Pittleworth Manor, via Brill. Fair use.] [Image 3, Pittleworth Manor, via Brill. Fair use.] [Image 4, Pittleworth Manor, with the inscription mentioning "poor Lazarus." Via Brill. Fair use.] [Image 5, Pittleworth Manor, featuring a bearded man at right at a banquet table with two women, and dogs under the table. Via Brill. Fair use.]

Pittleworth Manor is not far north of Southampton and Titchfield, both associated with Shakespeare's patron, Henry Wriothesley, 3rd earl of Southampton and Baron of Titchfield. Some over the years have claimed that Shakespeare was a school teacher in Titchfield in southern Hampshire. It would have been on the way from Stratford-upon-Avon to either Southampton or Titchfield for Shakespeare.

But this does not mean that Shakespeare might have stopped there or known the owners. More important is the observation that wall decorations like this were typical of the period, as were illustrations of other Biblical tales, painted on walls and carved into furniture and funerary monuments.

JACOPO BASSANO, 1550, ITALIAN

The image below of an italian painting by Jacopo Bassano was done in 1550, more than a decade before Shakespeare's birth.

[Lazarus and the Rich Man, 1550, by Jacopo Bassano (1510-92), Italian. Cleveland Museum of Art. Fair use.]

This rendering of the gospel story is interesting for how it foregrounds the beggar Lazarus: He is not marginalized, but rather, one must look over and past him, and perhaps past the son of the rich man as well, to see the rich man at his table. Will the son or boy pay any better heed to the beggar? Time will tell.

Given the fact that Shakespeare shifts his perspective and represents a variety of characters as analogous to the beggar Lazarus, this would seem significant. Even if Shakespeare was not familiar with this particular painting, experimentation with point of view was a characteristic of his age.

BARENT FABRITIUS, 1661

Barent Fabritius (1624-73) was born after Shakespeare's death in 1616, but his painting of Lazarus and the Rich Man has some features that foreground a servant (as do two later paintings considered). His method also harkens back to an older style of including many elements of the story in images in a non-chronological way, as if all moments of the story have some eternal character.

At the far left, the painting shows the rich man on his death bed some time in the near future. In the center are the rich man and his wife, but center left and foreground is the servant, and she is quite important to allow the rich man to enjoy a life of luxury. To the near right is what may be another servant, keeping the beggar Lazarus at bay, perhaps with a cane to strike him. To the far right and above are images from a slightly more distant future, with Lazarus in heaven, top right, and under him, the rich man in hell, or the torments that await him.

FORMERLY ATTR. PIETER CORNELISZ VAN RIJCK, 1610

The next painting had been attributed to Pieter Cornelisz van Rijck, whom Karl van Mander (I) said was a follower of Jacopo Bassano (above). One might notice that it seems to have been a tradition to place the rich man on the left in many of these renderings, and the beggar Lazarus on the right. But this painting challenges those expectations and not only foregrounds three servants (especially two women center and left), but also places both the rich man and his family, and also the beggar Lazarus, in the far back on the right, with an open door suggesting some heavenly judgment. [Kitchen Scene with the Parable of the Rich Man and Poor Lazarus. Anon, formerly attr. to Pieter Cornelisz van Rijck, circa 1610. Rijksmuseum, via Wikipedia. Image in the public domain.]

The scene is littered with dead animals of many kinds being prepared for the rich family's supper, and also a dog in the lower foreground growling at a cat, jcenter left. The viewer is forced to hunt for an image of the beggar, almost lost at the upper right, as if this should be a purpose in our lives, to pay attention, to notice the usually unnoticed beggar. Also almost lost is the image of the rich family: They are in a minority, while the servants in this culture seem to be what makes all the feeding occur. The servants here are the engine for the living, but perhaps also an obstruction: Even if we are among the servant class, we might forget to notice the beggar.

It is very possible that the servants portrayed here were actual servants to some family. But in a broader sense, even the servants here are beggars, in their own way, arresting the attention of the average viewer unfamiliar with the models who sat for the painting.

It is also possible that some rich families might give scraps of food to the poor, thinking they have done their duty, but still unfairly exploit the long and hard labors of their servants. To the rich, servants might be considered paid to be efficient and relatively invisible, always quite replacable as long as there are others willing to work hard and master the tasks. But when a painting like this foregrounds them in this way, they are rescued from invisibility and anonymity.

WORKSHOP OF DOMENICO FETTI, c.1618-28

The image below was created after Shakespeare's play was already performed and published, and in Italy, not England, and yet it demonstrates how artists who lived during Shakespeare's lifetime imagined the gospel tale. [The Parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man, from the Workshop of Domenico Fetti. National Gallery of Art. Samuel H. Kress Collection. Image is in the public domain. Via Wikipedia.]

Alfred Moir, in The Italian Followers of Caravaggio (1967, 2 vols., Harvard University Press) claims that Fetti was influenced in the direction of realism by Caravaggio. Instead of choirs of angels ready to take Lazarus to heaven, the artist shows us that the rich man has simulated the angelic choir in the form of musicians above the banquet, an irony. There is no roof, so we can see the clear blue sky representing the heavens, but there is no angry God looking down in judgment, and the rich man is left to his own devices, to ignore the beggar and be damned. The beggar Lazarus is in the bottom left, legs licked by dogs, but he is speaking to someone who looks above, not above the rich man's head, but above the heads of the viewers of the painting, and off to the left, as if mediating between the beggar and heaven.

And in the center at the bottom, between the rich man and Lazarus, is a hard-working servant, central here as if to imply that all of the luxury depicted in the painting is only present because of servants who work hard to do the bidding of the rich man. Service makes all of this hapen. Service creates the illusion for the rich man that the world is a comfortable place. Service is also a central theme in the gospels that Shakespeare was required to hear each Sunday of his life. And recall that service is what the rich man expects of Lazarus when the rich man is suffering in hell: Send Lazarus to wet my lips! Send Lazarus to warn my brothers! The rich man expects service, but does not offer it to others.

SERVANTS IN HAMLET

The images of servants that were included, and sometimes centered or foregrounded in paintings of Lazarus and the Rich man, might move us to reconsider the theme of servants in Shakespeare's Hamlet.

Prince Hamlet, in the first two scenes of the play, prefers the role of servant: He would change the names of "servant" and "lord" with Horatio, so that Hamlet could be servant. When the sentinels report to him of the strange aparition they have seen, and when Horatio and the sentinels leave with the greeting, "Our duty to your honor" (1.2.454), Hamlet responds as if to correct them: "Your loves, as mine to you" (455). For Hamlet, it is not about being served, but about mutual love.

Some might discount this as a thin veil of insincere flattery and hollow rhetoric, but it seems quite possible and even likely that Hamlet is sincere about placing mutual love over being served in duty. And in his role as servant-king, Hamlet begs, and is a beggar: He begs Horatio to be more friend than servant. He begs the sentinels for mutual love, and not merely duty and honor. He begs Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to be honest with him about whether they were sent for. And in the end, he begs forgiveness of Laertes. Inasmuch as many inspired painters, from different places and times, found it important to emphasize servants in their imagining of the Lazarus tale, perhaps Shakespeare brought together the servant and beggar in the person of the prince?

Polonius is supposed to be a sort of chief counsel and a kind of servant to the king, and he emphasizes his subordinate role at times, and yet when it comes to having the prince proclaim his love to Ophelia with "almost all the holy vows of heaven," suddenly Polonius is suspicious and unwilling to act as a servant to the prince as well as to the king and queen, unapproving and refusing to serve the goals Hamlet may have in love.

Laertes, one might think, should also be willing to serve the throne and royal family, but he is also suspicious and ungenerous when it comes to sharing his sister with the prince. As I have suggested in previous posts, Shakespeare may have fashioned the suspicions of Polonius and Laertes more to suit the suspicions of English audiences who knew the history of Henry VIII's love affairs, rather than to fit them to what Prince Hamlet deserved? Hamlet argues that the players should be given better lodging than they deserve, and that this can be to the honor of Polonius, if only he could bring himself to be so generous. This is the sort of generosity that they, perhaps, should have shown to Prince Hamlet, instead of advising Ophelia to keep her distance from him.

Ophelia acts as if it is a higher priority to her, to serve her father, than to serve her prince and beloved. She shows flashes of independence with her brother, father, and Hamlet, but especially with her father, these are quickly made irrelevant. If we read her remarks about the owl and the baker's daughter as regret for having been ungenerous with the beggar Hamlet, perhaps she is intent on acting like a humble and penitent servant to God? If we read her remarks about the false steward who stole his master's daughter as a reference to a Ben Jonson subplot (or older plot), perhaps she finds a truer spiritual parentage to serve, as well as a sense of her own worthiness? The gravedigger/clowns, interestingly, also demonstrate a certain dynamic of servant and master: the first clown wishes to project an air of superiority, as if he is the wise one, insightful in his mastery of law and the catechism. The second clown and Hamlet make their suggestions and ask their questions, but the first clown always has the witty response, and is the master. He sends the second clown to get him more drink, but he is never a cruel master. He does not realize he is speaking to the prince, so even with Hamlet, he is still the master of the jokes.

And perhaps this is appropriate, because as I have noted in previous blog posts, Hamlet and Horatio, the two Danes on the path to Elsinore, are like the two disciples on the road to Emmaus. Like the disciples, they encounter a stranger, who seems to embody the spirit of the jester Yorick, who is dead. It is an Emmaus encounter and a moment of grace for Hamlet, as it was for the disciples, who find in the stranger their master who insisted on washing their feet.

CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS:

My point in this blog post is not that Shakespeare was personally familiar with each of the art works considered, but that these are a range of samples demonstrating a variety of approaches. Certainly in Shakespeare's England, many works were lost to iconoclasm. Yet the playwright would still have experienced a diversity of visual interpretations, and this, in turn, may likely have encouraged Shakespeare to explore diverse ways the themes of the tale could be manifest in his play.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

INDEX OF POSTS IN THIS SERIES ON THE RICH MAN AND LAZARUS:

See this link:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2021/02/index-series-on-rich-man-and-beggar.html

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hamlet quotes: All quotes from Hamlet (in this particular series on The Rich Man and Lazarus in Hamlet) are taken from the Modern (spelling), Editor's Version at InternetShakespeare via the University of Victoria in Canada.

- To find them in the first place, I often use the advanced search feature at OpenSourceShakespeare.org.

Bible quotes from the Geneva translation, widely available to people of Shakespeare's time, are taken from an internet source somewhat close to their original spelling, from studybible.info, and in a modern spelling, from biblegateway.com.

- Quotes from the Bishop's bible, also available in Shakespeare's lifetime and read in church, are taken from studybible.info.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

YOU CAN SUPPORT ME on a one-time "tip" basis on Ko-Fi:

https://ko-fi.com/pauladrianfried

IF YOU WOULD PREFER to support me on a REGULAR basis,

you may do so on Ko-Fi, or here on Patreon:

https://patreon.com/PaulAdrianFried

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Disclaimer: If and when I quote or paraphrase bible passages or mention religion in many of my blog posts, I do not intend to promote any religion over another, nor am I attempting to promote religious belief in general; only to explore how the Bible and religion influenced Shakespeare, his plays, and his age.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

My current project is a book tentatively titled Hamlet’s Bible, about biblical allusions and plot echoes in Hamlet.

Below is a link to a list of some of my top posts (“greatest hits”), including a description of my book project (last item on the list):

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2019/12/top-20-hamlet-bible-posts.html

I post every week, so please visit as often as you like and consider FOLLOWING.

To find the FOLLOW button, go to the home page: https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/

see the = drop-down menu with three lines in the upper left.

From there you can click FOLLOW and see options.

Comments

Post a Comment