Lazarus & prodigals in Henry IV, Part I, & Hamlet

Before I conclude my series on the Lazarus allusion in Hamlet, let’s step back and consider his use of “Lazarus” and related terms in other plays. For today, consider: Shakespeare only uses the full word "Lazarus" once,* on the lips of Falstaff in Henry IV, Part I (1613).

[* According to the Advanced Search Engine at OpenSourceShakespeare.]

This single instance of "Lazarus" comes in a soliloquy in which Falstaff also happens to mention "prodigal," a reference to another tale from Luke's gospel.

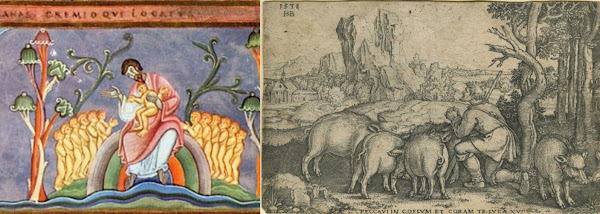

[Left: Detail from Lazarus and the Rich Man, Meister des Codex Aureus Epternacensis (1035-1040), via Wikipedia. Public domain.

Right: Der verlorene Sohn beim Schweinehüten (The Prodigal Son tending the Swine), 1538, by (Hans) Sebald Beham (1500-1550), via Wikipedia. Public domain.]

It so happens that there are allusions in Hamlet to both

Lazarus ("lazar-like," 1.5.79, Folger)

and the prodigal (Laertes 1.3.40, Polonius 1.3.125, Folger).

But these allusions are used strangely considering the larger contexts of the stories in the gospels, and their contexts in the plays, so all of this bears closer examination.

LAZARUS IN HENRY IV, PART 1

In Falstaff's soliloquy in 4.2, he says how he

profited greatly from his position of "pressing" or legally compelling

conscripts to become soldiers for the king in exchange for monetary rewards.

He describes what a motley bunch he pressed into service, using

references to both the beggar Lazarus (of Luke 16:19-31) and to the

prodigal son (of Luke 15:11-32). Falstaff speaks at first of being ashamed of his soldiers, but his second sentence implies reason for shame in himself, that he "misused the King's press damnably." Below, emphasis mine:

Falstaff:

If I be not ashamed of my soldiers, I am a

soused gurnet. I have misused the King’s press

damnably. I have got, in exchange of a hundred

and fifty soldiers, three hundred and odd pounds. I

press me none but good householders, yeomen’s

sons, inquire me out contracted bachelors, such as

had been asked twice on the banns—such a commodity

of warm slaves as had as lief hear the devil

as a drum, such as fear the report of a caliver worse

than a struck fowl or a hurt wild duck. I pressed me

none but such toasts-and-butter, with hearts in their

bellies no bigger than pins’ heads, and they have

bought out their services, and now my whole

charge consists of ancients, corporals, lieutenants,

gentlemen of companies—slaves as ragged as Lazarus

in the painted cloth, where the glutton’s dogs

licked his sores; and such as indeed were never

soldiers, but discarded, unjust servingmen, younger

sons to younger brothers, revolted tapsters, and

ostlers tradefallen, the cankers of a calm world and

a long peace, ten times more dishonorable-ragged

than an old feazed ancient; and such have I to fill up

the rooms of them as have bought out their services,

that you would think that I had a hundred and fifty

tattered prodigals lately come from swine-keeping,

from eating draff and husks. A mad fellow met me

on the way and told me I had unloaded all the

gibbets and pressed the dead bodies. No eye hath

seen such scarecrows. I’ll not march through Coventry

with them, that’s flat. Nay, and the villains

march wide betwixt the legs as if they had gyves on,

for indeed I had the most of them out of prison.

There’s not a shirt and a half in all my company,

and the half shirt is two napkins tacked together

and thrown over the shoulders like a herald’s coat

without sleeves; and the shirt, to say the truth,

stolen from my host at Saint Albans or the red-nose

innkeeper of Daventry. But that’s all one; they’ll find

linen enough on every hedge.

(H41.4.2.11-49)**

* Perhaps an ironic play on St. Paul, 1 Corinthians 2:9, "But as it is

written, The things which eye hath not seen, neither ear hath heard,

neither came into [b]man’s heart, are, which God hath prepared for them

that love him." This is a line that Bottom mixes up badly, to humorous

effect, in MSND.

[** From Henry IV, Part 1, Folger edition.]

It is clear from this passage that Shakespeare was very familiar with the

Luke 16 tale of the beggar Lazarus and the rich man, as well as with

the tale of the prodigal son in Luke 15.

It is also clear that Shakespeare shows compassion for those compelled into soldiering in this and other plays, and perhaps that he shows similar compassion for the sentinels in Hamlet.

LAZARUS ("LAZAR_LIKE") IN HAMLET

In my second installment in this series on the significances of the Lazarus allusion in Hamlet, I posed a question: If the ghost (of Hamlet's father?) was like the rich man, who was his Lazarus?

This may seem a leap to some: The ghost merely describes how the poison made his skin "lazar-like," or in other words, like the skin of the Biblical beggar Lazarus, whose sores were licked by dogs. Why, if the poison made his skin lazar-like, does that mean the ghost (or the dead king) was like the rich man, and he had neglected one or more Lazarus-beggar figures in his life?

But the leap to this conclusion seems necessary to explore, because the king, like the rich man, is not in heaven. He says he had "foul crimes" or sins still unforgiven. Like the rich man. In the Lazarus tale, after death, the beggar Lazarus goes to the comforts of heaven, and the rich man to hell. In other words, they switch places after death.

So if the ghost, after poison and death, found that he became more like Lazarus, but was locked out of heaven, at least for a time, then it would seem that receiving the skin of Lazarus was a fitting punishment for his foul crimes, and he probably neglected some beggars in his life.

In Henry IV, part 1, Falstaff probably will not repent of how he abused the Lazarus figures and prodigals among the soldiers he pressed into service so that he could profit. And the ghost in Hamlet did not repent before death of his sins, which seems to be why his skin became "lazar-like." It was not an effect of the poison, but an effect of the judgment of heaven, it would seem. Yet the ghost seems very unaware of this possibility. Which is probably why he needs to spend some time in purgatory, to have his blindness and his pride purged away to ready him for heaven, if that's what Shakespeare had in mind.

Otherwise, the ghost may be sent from hell to tempt Hamlet to revenge, and to confuse and taint his mind about all such things, to make him believe the lazar-like skin were caused by the poison (something more to revenge!) rather than by the judgment of heaven.

OBSERVATIONS:

Similarities:

1. Both the Luke 15 tale of the prodigal son and the Luke 16 tale of Lazarus and the rich man involve beggars.

2. In both tales, the beggar is saved in the end, and someone else is either damned (the rich man) or acting selfishly (the brother of the prodigal).

3. In both Biblical tales, the person the story invites us to view critically in the end stands for the Jewish authorities who either abused the wealth from their position (like the rich man) or abused their religious authority by judging others and nit-picking about the law (the prodigal's brother).

Gospel Differences:

Among the differences between the tales:

- The Luke 16 tale of the beggar Lazarus portrays the beggar as simply poor and suffering from a skin ailment. It does not praise the beggar for being virtuous or just or in need of repentance, but he goes to heaven, and the rich man goes to hell.

- Unlike Lazarus, the prodigal in Luke 15 has a fall from riches and from favor after he wastes his inheritance selfishly; but the prodigal resolves to mend his ways and, in humility, goes home to ask to become a servant for his father's house, because in his shame, he feels he deserves no more than this.

- So Lazarus does not need to repent, and goes to heaven, while the prodigal needs to repent, and does, and is welcomed by the father. This seems to be Jesus' alegory for how his heavenly father welcomes sinners, and why Jesus himself spent so much time with known sinners.

[Falstaff, 1906, by Eduard von Grützner (1846 – 1925), via Wikipedia. Public domain.]

Falstaff-Gospel Contrasts

Falstaff admits in his second sentence that he has "misused the King's press damnably." He also misused the soldiers in the process, as many of them were not fit to serve. He goes on to portray them as including Lazarus-beggar types, and prodigals.

The emphasis in the gospels is not on how the beggars were exploited, or even how the owner of the herd of swine exploited the labor of the prodigal, but rather on how the rich man ignored or was indifferent to the beggar, and how the brother was ungenerous and envious when his prodigal brother was welcomed home as God welcomes the repentant sinner.

But unlike the emphasis in these gospel tales, Falstaff views himself as having exploited both types of beggars, Lazarus and prodigal. In that way, Falstaff is perhaps worse than both the envious brother of the prodigal, and the rich man whose sin was merely indifference, ignoring the beggar. Falstaff has seen both types of beggars in the soldiers he has recruited, but he exploited them as an opportunity to make some fast money.

The Attraction and Catharsis of an Unrepentant Falstaff

While Falstaff regrets what he has done, he is, after all, a man who famously enjoys his sins and has little intention of repenting. One of the many reasons Falstaff is an attractive character is that in him, we can see a humorous image of that part of ourselves that enjoys sin and refuses to repent.

[Edit: But in this instance, he also has great appeal because he feels shame for profiting from the crown by pressing unfit conscripts into soldiering. People in Shakespeare's England may have had strong feelings about the sort of people who would do this, and Falstaff, as a clown, gives audiences a humorous outlet for their pent-up frustration about how the system, or the political establishment, works in this way. If Falstaff feels shame for doing this, then it implies that there are others in Shakespeare's society who should feel shame for it, but perhaps do not. Unvirtuous people (like Falstaff in that way) go out and oppress average people, and the low-born, and profit from it, while they are taking men from families.

What can be done? One can't change the system if one is attending a Shakespeare play in the cheap seats. But if one is a playwright, one can give these lines to Falstaff: This reminds audiences of the problem, and affirms their frustration, even if nothing can be done.]

Hamlet & Hal, Yorick and Falstaff: Connections to Hamlet

Both Hamlet and Hal (later King Henry V) have strained, distant relationships with their fathers, and both sought surrogate fathers in clown/fool figures, Hamlet in Yorick, and Hal in Falstaff. - Hamlet speaks more affectionately of Yorick than he does of the distant father he can only idolize with analogies of classical gods and titans. - Hamlet lost Yorick when the Danish court jester died, but he seems to find another surrogate father-figure on the sea-voyage to England, convinced that he is being watched and perhaps aided by "Providence" (another Elizabethan name for the Christian monotheistic God).

- Similarly, Hal doesn't only have Falstaff as a surrogate father, but Kenji Yoshino has argued that the Lord Chief Justice later becomes a more legitimate father-figure, and his father-in-law, the King of France, also fills something like the role of a legitimating father, considering his biological father had usurped the throne from Richard II.

Are All Alienated Sons Figuratively Prodigals and Beggars?

In a recent post, I mentioned that Patrick Page of the cast of Hadestown had made connections in one of his podcasts between Hamlet and a book by poet Robert Bly called Iron John: A Book About Men. Bly might say that all boys move from the mother's house toward the father's house, but that movement is sometimes a difficult one, especially when sons are alienated from their fathers for some reason.

One might say that in the Luke 15 gospel tale of the prodigal son, the son who takes and wastes his share of the inheritance has had difficulty moving from the mother's house, where he is care for by the mother, to the father's house, where he becomes responsible as a man. If the father's house comes with an inheritance of riches, well, think how much drinking and gambling could be financed by such money. It is as if the prodigal imagines he might suck forever from the teat of a generous parent, without any responsibilities, moving from the mother's milk to the father's money.

But by the consequences of his own wasteful life, he runs out of money and becomes a hired hand, taking care of swine, an animal whose meat was considered unclean for Jews to eat. Realizing how far he has fallen, he goes back home as a beggar, seeking to become a servant.

He becomes a prodigal first, a wastrel. and then, after the money runs out, he becomes a kind of beggar, begging for whatever low form of work people are willing to give him. In his wasteful lifestyle, he never thought to acquire any marketable skills.

Bly notes that young men often withdraw, tending the fire, seeming to waste time. They also sometimes settle for work they only wish to keep short-term, to earn money, but to keep themselves free from greater attachments, responsibilities, or a sense of a life-long vocation. They are in this sense somewhat like beggars, begging for work, perhaps working hard, but begging for freedom as well.

[Der verlorene Sohn beim Schweinehüten (The Prodigal Son tending the Swine), 1538, by (Hans) Sebald Beham (1500-1550), via Wikipedia. Public domain.]

Literal and Figurative Prodigals in Hamlet

We might note that while Laertes and Polonius warn Ophelia of becoming a prodigal (sexually) in her love for Hamlet, it's really Laertes who his sister and father suspects will go back to France and live like a prodigal. And in another sense, both Hamlet and Laertes are "prodigal" sinners who stray when tempted toward revenge, but eventually come back home to a moment of reconciliation in the final scene, where they exchange forgiveness, welcoming one another with the kind of mercy shown the prodigal by his father in the Luke 15 tale.

In that sense, Hamlet's time of feigned or real madness seems his wasteful, prodigal time, during which he estranges himself from Ophelia, and (during "The Mousetrap") from Gertrude and Claudis, and kills Polonius.

But after the Jonah-like sea-voyage and the pirates, the help of Providence, and the unexpected memory of Yorick in the graveyard (which I've called an "Emmaus" moment), he repents of his prodigal ways (and feigned madness). Revenge is no longer foremost in his mind, and neither is his biological father, who is barely mentioned after the sea-voyage.

By the time Hamlet shows up for the sword duel with Laertes, ready to apologize to him, he has effectively moved from the mother's house, not to his biological father's house, but perhaps to the house of his newest surrogate father, Providence. [Return of the Prodigal Son, circa 1619, Giovanni Francesco Barbieri ("Guercino"), 1591 – 1666. Via Wikipedia, public domain. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien.]

Literal and Figurative Prodigals in the Henriad

Similarly, Hal has a hard time moving to the father's house, and he becomes a kind of prodigal in search for drinking buddies. He finds a drinking buddy, a surrogate father, and a kindred prodigal son in Falstaff.

Hal's dad, Henry IV, feels himself a kind of prodigal, a sinner for having usurped the throne from Richard II. Does Hal run from his father because he knows his father is a questionably legitimate king, so why not be a questionably legitimate heir and prodigal son? Perhaps.

But as many scholars of Shakespeare's Henriad have noted, Hal comes to the end of his inheritance when his father threatens that perhaps Hal is not suited to be the heir to the throne. Hal decides it is time for him to change his path, and to take steps to mend his relationship with his biological father, and to radically change his relationship with Falstaff. If and when Falstaff changes in like manner, he might again be welcome.

Good, Evil, and Good Being Better for Having Known Evil?

There is a sense in Shakespeare about repentant prodigals being even better for having known evil. This is perhaps especially so in Henry V, Measure for Measure (perhaps stumblingly?) and perhaps Hamlet also, that morality is not merely about good and evil as black and white, but about something more complicated: to still kill Claudius, but not merely in a blind lust for revenge, but to fix what was out of joint in Denmark.

I will have to explore this at greater length in a future post, but in short, after Hal repents of his prodigal ways, he becomes a better king for having known evil. Hamlet (perhaps, or at least I would argue) becomes a better prince, and more king-like, for having known what the careless passion for revenge did in him. Mariana claims Angelo can be a better husband for having known evil in himself, in his lust for Isabella and in his betrayal of his promise to her, to spare her brother's life. (Whether that possibility is realistically achieved or even suggested for their future by the play is another thing....)

I intended only to explore what might be revealed in the differences between how the themes of Lazarus and the prodigals are handled in the Henriad and in Hamlet, but now I'm on the precipice of a new topic. A good place to end.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

INDEX OF POSTS IN THIS SERIES ON THE RICH MAN AND LAZARUS:

See this link:

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2021/02/index-series-on-rich-man-and-beggar.html

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hamlet quotes: All quotes from Hamlet (in this particular series on The Rich Man and Lazarus in Hamlet) are taken from the Modern (spelling), Editor's Version at InternetShakespeare via the University of Victoria in Canada.

- To find them in the first place, I often use the advanced search feature at OpenSourceShakespeare.org.

Bible quotes from the Geneva translation, widely available to people of Shakespeare's time, are taken from an internet source somewhat close to their original spelling, from studybible.info, and in a modern spelling, from biblegateway.com.

- Quotes from the Bishop's bible, also available in Shakespeare's lifetime and read in church, are taken from studybible.info.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

YOU CAN SUPPORT ME on a one-time "tip" basis on Ko-Fi:

https://ko-fi.com/pauladrianfried

IF YOU WOULD PREFER to support me on a REGULAR basis,

you may do so on Ko-Fi, or here on Patreon:

https://patreon.com/PaulAdrianFried

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Disclaimer: If and when I quote or paraphrase bible passages or mention religion in many of my blog posts, I do not intend to promote any religion over another, nor am I attempting to promote religious belief in general; only to explore how the Bible and religion influenced Shakespeare, his plays, and his age.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

My current project is a book tentatively titled Hamlet’s Bible, about biblical allusions and plot echoes in Hamlet.

Below is a link to a list of some of my top posts (“greatest hits”), including a description of my book project (last item on the list):

https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/2019/12/top-20-hamlet-bible-posts.html

I post every week, so please visit as often as you like and consider FOLLOWING.

To find the FOLLOW button, go to the home page: https://pauladrianfried.blogspot.com/

see the = drop-down menu with three lines in the upper left.

From there you can click FOLLOW and see options.

Comments

Post a Comment